Market Street in Philadelphia, a major east-west artery, began as “High Street” in William Penn and Thomas Holme’s visionary city plan of 1682. Designed to be a grand 100 feet wide and centrally located, Penn’s understanding of urban health and safety shaped its very foundation. This wide expanse, inspired by the Great Fire of London and concerns about disease spread, not only aimed to protect against calamities but also destined Market Street for a pivotal role in Philadelphia’s geographical, economic, and social evolution. Hailed as “America’s most historic highway,” Market Street stretched nearly seven miles from the Delaware River at Front Street to Cobbs Creek, the city’s western edge, and continued westward as Route 3.

A color illustration depicting Market Street in the late 1700s, showcasing the old Court House and Christ Church on the left.

A color illustration depicting Market Street in the late 1700s, showcasing the old Court House and Christ Church on the left.

The Genesis of a City Center: Market Street in the 18th Century

The blocks of High Street nearest to the bustling Delaware River quickly became Philadelphia’s commercial and civic heart in the 1700s. Key institutions sprung up along or near Market Street, including the Town Hall and Courthouse (1707), the iconic Christ Church (1744), the London Coffeehouse (1754), and the Great Meetinghouse of the Quakers (1755). Reflecting the growing need for order in a rapidly expanding and diverse Philadelphia, a new jail was constructed in 1722 at Third and High Street, replacing a rudimentary log jail. This larger facility, separating debtors from criminals, served the city until the late 1770s, underscoring Market Street’s central role in Philadelphia’s civic infrastructure.

High Street also became home to prominent Philadelphians. Benjamin Franklin resided between Third and Fourth Streets, while financier Robert Morris lived between Fifth and Sixth, and builder Jacob Graff made his home at Seventh Street. The burgeoning publishing industry also took root here, with newspapers like the Pennsylvania Herald and Pennsylvania Gazette operating west of Third Street. Publishers and engravers such as William Bradford, John Dunlap, and Mary Katherine Goddard, who famously first published the Declaration of Independence with signatories’ names, established businesses on Market Street. Taverns like the Indian King became social hubs, attracting Franklin’s “Junto,” a group dedicated to civic improvement. The lively atmosphere of Market Street was even celebrated in verse, as Joseph Breintnall, a friend of Franklin, penned “A plain description of one single street in this city” in 1729, capturing its vibrant energy.

A historic black and white photograph showcasing market sheds extending down the median of Market Street, with streetcar tracks on either side.

A historic black and white photograph showcasing market sheds extending down the median of Market Street, with streetcar tracks on either side.

The year 1745 marked the beginning of a transformation that would informally, and later officially, rename High Street. Construction began on the High Street Market, a central marketplace with vendor stalls, stretching initially from Front to Second Streets and later to Third Street by 1759. This bustling market, located in the street’s median, became the largest in the American colonies, offering a wide array of goods and solidifying the street’s identity as Market Street, a name officially adopted in 1854.

Market Street: Crucible of Revolution

As tensions escalated with British rule in the late eighteenth century, Market Street became a focal point of revolutionary fervor. Thomas Jefferson famously rented rooms at Jacob Graff’s house on Seventh Street, where he drafted the Declaration of Independence in June 1776. The former jail at Third Street was repurposed as a military headquarters for the Continental Army and a detention center for British loyalists once hostilities commenced. During the British occupation of Philadelphia in the winter of 1777-78, General William Howe established his headquarters at the Governor’s Mansion (Masters-Penn House) on Sixth Street. Following the British retreat in 1778, General Benedict Arnold, residing in the same house, began his infamous plot to defect to the British. After the war, Robert Morris acquired and expanded this significant property. In December 1783, George Washington, on his way to resign his commission, was greeted with jubilant celebrations as his procession moved east along Market Street, marking the street as a stage for pivotal moments in American history.

Philadelphia’s designation as the nation’s capital further elevated Market Street’s residential and commercial prominence. In 1790, Robert Morris offered his Market Street residence to the executive branch, becoming the President’s House where George Washington lived until 1797, followed by John Adams until 1800 when the capital moved to Washington, D.C. A second presidential mansion, built in 1792 at Ninth and Market, never housed a president but instead became home to the College of Philadelphia, later the University of Pennsylvania.

For entertainment, John Bill Ricketts established the nation’s first circus in 1793 at Twelfth Street on Market Street. This amphitheater, featuring equestrian performances and acrobats, also served as a quarantine facility during the yellow fever epidemic that summer, highlighting the street’s adaptability to the city’s needs.

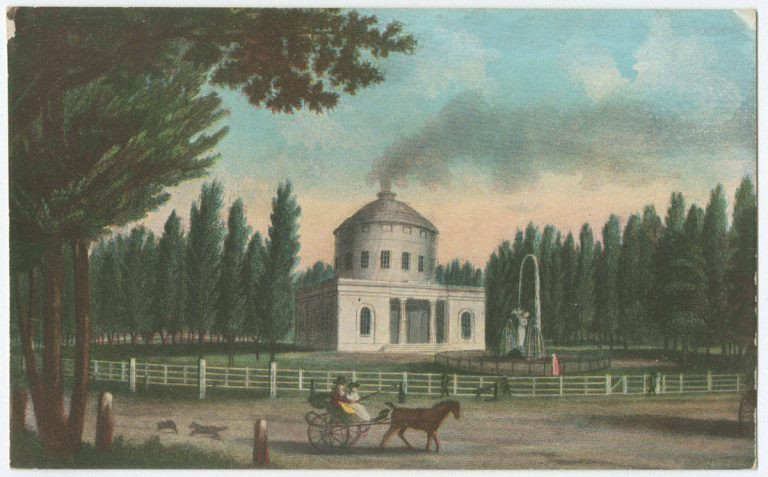

An image of the Centre Square Pump House, showcasing the first water works at the intersection of Market and Broad Streets.

An image of the Centre Square Pump House, showcasing the first water works at the intersection of Market and Broad Streets.

After 1800, Market Street’s commercial landscape diversified. Apothecaries, shipping firms, hotels, booksellers, jewelers, and umbrella manufacturers joined the mix. Chef M. Latouche’s restaurant and oyster cellar at Fifth Street catered to the city’s refined tastes in the 1810s. Despite Penn’s vision for westward expansion, significant development west of Twelfth Street was limited initially. However, a notable exception began in 1801 with Benjamin Henry Latrobe’s Greek Revival-style pump house for the Philadelphia Waterworks in Centre Square (later City Hall). The Columbian Garden, a “pleasure garden” for leisure and entertainment, opened nearby in 1813, transforming Centre Square into a popular gathering place, foreshadowing its future as Philadelphia’s civic center.

Bridges and Broad Street Station: Market Street in the 19th Century

The early 1800s saw Philadelphia expanding westward, necessitating bridges to replace ferries. Judge Richard Peters championed the construction of Market Street’s first permanent bridge over the Schuylkill River, opening in 1805. Designed by Timothy Palmer, this covered bridge, the world’s largest at the time, spurred development west of the Schuylkill, transforming former farmlands and potter’s fields. Lodging like the Golden Fish and William Penn Inn emerged near the bridge to serve increased traffic between the city and its western areas. By the 1840s, this section of Market Street also housed engineering and manufacturing businesses.

A black and white photograph of Broad Street Station, a grand Gothic Revival building with an attached train shed and viaduct.

A black and white photograph of Broad Street Station, a grand Gothic Revival building with an attached train shed and viaduct.

The consolidation of Philadelphia County in 1854 expanded the city significantly. In 1858, High Street officially became Market Street, extending to the new city limits. Market Street’s transportation role grew alongside industry and population. The High Street Market was demolished between 1859 and 1860 to make way for Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) trolley lines. The PRR, a major player during the Civil War, established streetcar terminals on Market Street at Eighth and Eleventh Streets. In 1864, a terminal for locomotives opened at Thirty-First and Market. After the war, the PRR built its main Broad Street Station at Fifteenth and Market. Designed by Frank Furness, this Gothic-style station, featuring the world’s largest train shed, opened in 1881. A massive viaduct, known as the “Chinese Wall,” extended along Market from Broad Street Station to the Schuylkill River, facilitating rail traffic.

Market Street’s governmental and commercial importance continued to rise. Construction of a new City Hall in Centre Square began in 1871, designed by John McArthur Jr. This French Second Empire building, completed in 1901, became the world’s largest municipal building, occupying the entire Centre Square and necessitating traffic rerouting around Market Street. Market Street also emerged as the city’s premier retail destination. In 1876, John Wanamaker opened his pioneering department store at Thirteenth Street. Wanamaker’s Grand Depot, catering to an upscale clientele, included amenities like a restaurant, electric lighting, and elevators. A larger twelve-story store replaced it in 1910, famous for its grand organ and bronze eagle statue. Lit Brothers’ department store arrived at Eighth and Market in 1893, followed by Gimbel’s at Ninth and Market in 1894. Gimbel’s launched Philadelphia’s first Thanksgiving Day parade in 1920, running along Market Street from City Hall. Strawbridge and Clothier, established at Eighth and Market in 1861, moved into its flagship building there in 1932. These department stores, along with Snellenburg’s and Frank and Seder, offered Philadelphians unparalleled shopping experiences on Market Street.

A black and white photograph of people waiting for a streetcar beneath the elevated tracks of the Market Frankford Line.

A black and white photograph of people waiting for a streetcar beneath the elevated tracks of the Market Frankford Line.

20th Century Transformation and Beyond

At the dawn of the 20th century, Market Street’s success led to congestion. In 1905, the Market Street Elevated (“El”) train line began service between Fifteenth Street and the Schuylkill River. Extended to Sixty-Ninth Street in 1907 and eastward to Second Street in 1908, the El, along with PRR’s ferry terminal, alleviated street congestion and improved access to Market Street’s amenities for suburban residents. Connections to trolley lines in West Philadelphia spurred residential growth west of the Schuylkill. The Great Migration during World War I significantly increased West Philadelphia’s African American population, doubling its overall population by 1920 and shifting some commercial activity away from Center City towards areas around train stations at Fifty-Second and Fifty-Sixth Streets. Educational institutions also grew near Market Street, with the University of Pennsylvania establishing its campus south of Market Street in 1872 and Drexel Institute (Drexel University) opening south of Market at Thirty-First Street in 1891.

Before 1890, Market Street buildings rarely exceeded six stories. The skyscraper era changed this. The fourteen-story Betz Building, designed by William H. Decker, opened on Centre Square in 1892. Other early skyscrapers on Centre Square included the West End Trust Building (1898) and the Market Street National Bank (1929). The Great Depression slowed construction, but the Philadelphia Saving Fund Society (PSFS) tower, completed in 1932 on the former Ricketts’ Circus site, stood as a symbol of modernity. Designed in the International Style by George Howe and William Lescaze, it was among the most advanced office buildings of its time.

A black and white photograph of the Betz Building, a tall stone structure on the corner of Center Square.

A black and white photograph of the Betz Building, a tall stone structure on the corner of Center Square.

Post-World War II, Market Street underwent another transformation, particularly west of City Hall. Demolition of Broad Street Station and the “Chinese Wall” in 1953 paved the way for Penn Center, a modern complex of office buildings, retail spaces, and plazas. This project spurred growth in the Market West corridor, which saw numerous office towers, hotels, and residential buildings in the following decades. In 1985, developer Willard G. Rouse III facilitated the construction of Liberty Place at Sixteenth and Market Streets. Completed in 1987, Liberty Place famously broke the city’s height restriction, surpassing William Penn’s statue atop City Hall. Transit development continued with the Center City Connector tunnel in 1984, enhancing access to Market Street businesses.

In 1952, Bandstand (later American Bandstand) debuted at Forty-Sixth Street and Market, broadcasting Philadelphia’s youth culture nationally and further cementing Market Street’s cultural significance. Drexel and Penn continued to expand their campuses around Market Street in the 1990s and 2000s.

However, retail on Market Street in Center City declined after World War II. Major department stores like Snellenburg’s, Frank and Seder, Lit Brothers, and Gimbel’s closed by the late 1970s. Wanamaker’s was acquired in 1978, and Strawbridge & Clothier closed in 1996. In Old City, manufacturing declined in the 1970s, leading to artists and creative professionals converting industrial spaces into lofts near Market Street. By the early 1990s, a vibrant nightlife scene emerged with restaurants, bars, and clubs. In the mid-2010s, the Philadelphia Inquirer and Philadelphia Daily News relocated to the former Strawbridge’s building, with discount retailer Century 21 opening on its ground floors in 2014.

In the 2010s, Market Street continued to be a site of new development and civic events, remaining a vital thoroughfare and the dividing line for Philadelphia’s numbered streets. Despite changes over centuries, Market Street’s enduring importance to Philadelphia’s economy, social fabric, and transportation network remains undeniable.

Further Reading:

- Cheape, Charles W. Moving the Masses: Urban Public Transit in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, 1880-1912. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980.

- Jackson, Joseph. America’s Most Historic Highway, Market Street, Philadelphia, 2nd Ed. Philadelphia: J. Wanamaker, 1926.

- Weigley, Russell ed. Philadelphia: A 300-Year History. New York: Norton, 1982.