Market Street in Philadelphia, originally conceived as High Street, is more than just a road; it’s a vibrant artery pulsating with the city’s history, commerce, and social life. Planned in 1682 by William Penn and Thomas Holme, this grand thoroughfare, envisioned at a generous hundred feet wide, was strategically positioned at the longitudinal heart of Philadelphia. Penn, drawing from the lessons of London’s Great Plague and devastating fire of the 1660s, designed High Street’s breadth to serve as a safeguard against disease and fire, while unknowingly laying the groundwork for its pivotal role in Philadelphia’s future. Famously dubbed “America’s most historic highway,” Market Street stretches nearly seven miles from the Delaware River waterfront to Cobbs Creek, the city’s western edge, and continues westward as Route 3 into the surrounding counties, weaving through the very fabric of southeastern Pennsylvania.

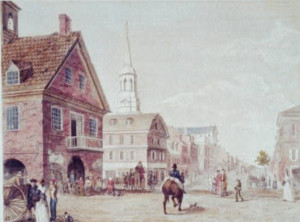

An eighteenth-century illustration of Market Street in Philadelphia, showcasing the old Court House and Christ Church on the left, highlighting the early civic and religious institutions along High Street.

An eighteenth-century illustration of Market Street in Philadelphia, showcasing the old Court House and Christ Church on the left, highlighting the early civic and religious institutions along High Street.

Early civic institutions on Market Street, Philadelphia, depicted in an illustration by William Birch. The image features the first city court house and Christ Church, underscoring the street’s historical importance.

From its inception, High Street became the nucleus of Philadelphia’s civic and commercial activities. The blocks closest to the bustling Delaware River quickly evolved into the city’s nerve center. Landmark institutions like the Town Hall and Courthouse (1707), the iconic Christ Church (1744), the bustling London Coffeehouse (1754), and the Quakers’ Great Meetinghouse (1755) were all established on or near High Street, between Front and Second Streets. By 1722, reflecting the growing urban complexity, the city constructed a substantial jail at Third and High Street, replacing a rudimentary log-house jail. This new facility, comprising two stone buildings, reflected the era’s evolving approach to law and order in a rapidly growing and diverse Philadelphia, separately housing criminals and debtors until the late 1770s.

High Street also became the prestigious address for notable Philadelphians. Benjamin Franklin, the quintessential American polymath, resided between Third and Fourth Streets. Financier Robert Morris, crucial to the American Revolution’s funding, lived between Fifth and Sixth, and builder Jacob Graff, whose home would later host Thomas Jefferson, resided at Seventh Street. The burgeoning world of print media also found its home here, with newspapers like the Pennsylvania Herald and Pennsylvania Gazette operating west of Third Street. Printers and publishers of renown, including William Bradford, John Dunlap, and Mary Katherine Goddard, who first dared to publish the Declaration of Independence with the signatories’ names, established their businesses on High Street. Taverns, vital social and political hubs of the time, dotted the streetscape. The Indian King Tavern became famous as the meeting place for Franklin’s “Junto,” a group dedicated to civic improvement. In 1729, Joseph Breintnall, Franklin’s friend and Junto member, captured the vibrant energy of Market Street in his poem “A plain description of one single street in this city,” immortalizing its bustling atmosphere.

A historic black and white photograph showing the market sheds running down the center of Market Street in Philadelphia, with streetcar tracks visible on either side, capturing the street's evolution as a marketplace and transportation corridor.

A historic black and white photograph showing the market sheds running down the center of Market Street in Philadelphia, with streetcar tracks visible on either side, capturing the street's evolution as a marketplace and transportation corridor.

Market sheds on Market Street in the 1850s, showcasing the street’s transformation into a bustling marketplace, colloquially known as Market Street after the High Street Market.

In 1745, construction began on the High Street Market, a defining feature that would eventually give the street its popular and later official name. This market, initially stretching from Front to Second Streets and later extended to Third Street by 1759, became the largest in the American colonies, offering a wide array of goods from vendor stalls lining the street’s center. While officially named High Street in Penn’s plan, the colloquial usage of Market Street, derived from this central marketplace, gained prominence and became the official name in 1854, permanently altering Philadelphia’s map and identity.

Market Street: Cradle of Revolution

As tensions escalated with British rule in the late eighteenth century, Market Street transformed into a hotbed of revolutionary fervor. Thomas Jefferson, in June 1776, famously rented rooms at Jacob Graff’s house on Seventh Street, where he penned the Declaration of Independence, a document that would reshape the world. The former jail at Third Street was repurposed as a military headquarters for the Continental Army and a detention center for British loyalists once hostilities commenced. During the British occupation of Philadelphia in the winter of 1777-78, General William Howe established his headquarters in the Governor’s Mansion (Masters-Penn House) on Sixth Street. Intriguingly, after the British withdrawal, General Benedict Arnold, while residing in the same mansion, began his infamous plot to defect to the British.

Following the war, Robert Morris acquired and expanded this historically significant property. In December 1783, George Washington, en route to Annapolis to resign his commission, was greeted by cheering crowds and celebratory sounds as his procession moved eastward along Market Street, marking a pivotal moment in the nascent nation’s history.

Philadelphia’s designation as the nation’s capital further amplified Market Street’s significance. In 1790, Robert Morris offered his residence for the executive branch, and President Washington resided there until 1797. John Adams succeeded him, living in the same house until the capital relocated to Washington, D.C., in 1800. After Adams’ departure, the building became the Union Hotel. A newer presidential mansion, constructed in 1792 at Ninth and Market, was never occupied by a sitting president but instead served as the home of the College of Philadelphia, later the University of Pennsylvania, until 1829.

For entertainment, John Bill Ricketts opened the nation’s first circus in 1793 at Twelfth Street, on the western edge of the city’s development. This amphitheater, offering equestrian performances and acrobatics, also served a grim purpose as a quarantine facility during the devastating yellow fever epidemic that summer.

At the intersection of Market and Broad Streets, Philadelphia’s first waterworks were constructed in 1801 on Centre Square, the future site of City Hall. The Centre Square Pump House was crucial in providing clean water to city residents, addressing the critical public health issues of the time.

Commercial activities along Market Street continued to diversify into the 1800s. Apothecaries, shipping firms, new hotels, booksellers, jewelers, and umbrella manufacturers flourished. Chef M. Latouche operated a renowned restaurant and oyster cellar at Fifth Street in the 1810s, catering to the city’s growing refined tastes. Despite Penn’s vision for westward expansion, significant development west of Twelfth Street was slow. However, in 1801, architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe began constructing a Greek Revival-style pump house for the Philadelphia Waterworks in Centre Square, fulfilling Penn’s original vision of this space as the city’s administrative heart. The Columbian Garden, a “pleasure garden” offering food and entertainment, opened in 1813 east of the pump house, solidifying Centre Square as a popular gathering spot and foreshadowing its future as Philadelphia’s civic core.

Bridges and Broad Street Station: Market Street in the Industrial Age

As Philadelphia expanded westward in the early nineteenth century, bridges became essential, replacing unreliable ferry crossings. Judge Richard Peters championed the construction of Market Street’s first permanent bridge over the Schuylkill River, which opened in 1805. Designed by Timothy Palmer, this covered bridge, the largest of its kind at the time, spurred development west of the Schuylkill, transforming former rural areas into burgeoning suburbs. Lodging facilities like the Golden Fish and the William Penn Inn sprang up near the bridge to accommodate the increased traffic. By the 1840s, this area of Market Street also became a hub for engineering and manufacturing enterprises.

A black and white photograph of Broad Street Station in Philadelphia, a grand Gothic Revival structure featuring a church-like steeple and a vast train shed extending into the distance, illustrating Market Street's crucial role in transportation history.

A black and white photograph of Broad Street Station in Philadelphia, a grand Gothic Revival structure featuring a church-like steeple and a vast train shed extending into the distance, illustrating Market Street's crucial role in transportation history.

Broad Street Station, a monumental Gothic Revival train station on Market Street, symbolizing Philadelphia’s transportation prominence in the late 19th century.

The consolidation of Philadelphia County’s townships in 1854 dramatically expanded the city’s territory. In 1858, High Street officially became Market Street, extending to the city’s new western boundary. As industry and population boomed, Market Street’s role as a transportation and commercial artery intensified. Between 1859 and 1860, the High Street Market, which had expanded to Eighth Street and beyond, was demolished to make way for Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) trolley lines. The PRR, a major force during the Civil War, established Market Street streetcar terminals at Eighth and Eleventh Streets. In 1864, a locomotive terminal opened at Thirty-First and Market. After the war, the PRR constructed its grand Broad Street Station at Fifteenth and Market. Designed by Philadelphia architect Frank Furness, this Gothic-style station, with its enormous train shed, opened in 1881. To manage rail traffic, the “Chinese Wall” viaduct was built, stretching along Market Street from Broad Street Station west to the Schuylkill River.

Market Street’s civic and commercial importance continued to grow. Construction began on Philadelphia City Hall at Centre Square in 1871. Designed by John McArthur Jr. in the French Second Empire style, City Hall, upon its completion in 1901, became the world’s largest municipal building, dominating Centre Square and necessitating traffic rerouting around Market Street. Market Street also emerged as the city’s premier retail destination. In 1876, John Wanamaker opened his pioneering department store at Thirteenth Street. Wanamaker’s Grand Depot, catering to an upscale clientele, featured innovations like electric lighting and elevators. In 1910, a larger, twelve-story Wanamaker’s store opened on the same site, famed for its grand organ and bronze eagle. Lit Brothers’ department store arrived at Eighth and Market in 1893, followed by Gimbel’s at Ninth and Market in 1894. Gimbel’s launched Philadelphia’s first Thanksgiving Day parade in 1920, running along Market Street. Strawbridge and Clothier, established at Eighth and Market in 1861, moved into its flagship building in 1932. These department stores, alongside Snellenburg’s and Frank and Seder, transformed Market Street into a retail paradise for the region.

A black and white photograph of a group of people waiting to board a streetcar under the elevated tracks of the Market Frankford Line, illustrating the development of public transportation on Market Street in Philadelphia.

A black and white photograph of a group of people waiting to board a streetcar under the elevated tracks of the Market Frankford Line, illustrating the development of public transportation on Market Street in Philadelphia.

Passengers awaiting a streetcar beneath the Market Street Elevated line, highlighting the evolution of public transit and its impact on Market Street’s accessibility.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, Market Street’s success led to traffic congestion. In 1905, the Market Street Elevated (“El”) train line began service between Fifteenth Street and the Schuylkill River. Extended west to Sixty-Ninth Street in 1907 and east to Second Street in 1908, and connecting with the PRR’s Delaware River ferry terminal, the El and subway lines eased congestion and provided faster access to Market Street’s attractions for suburban residents. The Market Street lines spurred residential growth in West Philadelphia, especially with the Great Migration during World War I. West Philadelphia’s population more than doubled by 1920, and commercial activity began to shift westward. The University of Pennsylvania established its campus south of Market Street in 1872, and Drexel Institute (later Drexel University) opened near Thirty-First and Market in 1891, further anchoring the street’s western reaches.

Skyscrapers and Post-War Transformation

Before 1890, Market Street’s buildings were generally no taller than six stories. The skyscraper era dramatically changed the skyline. In 1892, the fourteen-story Betz Building opened at Centre Square’s southeast corner. Other early skyscrapers included the West End Trust Building (1898) and the Market Street National Bank (1929). The Great Depression slowed construction, but the iconic PSFS tower, completed in 1932 on the former Ricketts’ Circus site, stood as a testament to modern architecture. Designed in the International Style by George Howe and William Lescaze, it was one of the most advanced office buildings of its time.

A black and white photograph of the Betz Building in Philadelphia, a fourteen-story office building on the corner of Center Square, representing the early skyscrapers along Market Street.

A black and white photograph of the Betz Building in Philadelphia, a fourteen-story office building on the corner of Center Square, representing the early skyscrapers along Market Street.

The Betz Building, an early skyscraper on Market Street, marking the street’s architectural evolution towards taller structures in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Market Street underwent another major transformation after World War II, particularly west of City Hall. The demolition of Broad Street Station and the “Chinese Wall” in 1953 paved the way for Penn Center, a modern urban renewal project featuring office buildings, retail spaces, and plazas. Penn Center spurred development in the Market West corridor, leading to the construction of numerous office towers, hotels, and residential buildings over the next decades. In 1985, developer Willard G. Rouse III secured permission to build Liberty Place at Sixteenth and Market Streets. Completed in 1987, Liberty Place famously broke the city’s height restriction that had limited buildings to below William Penn’s statue atop City Hall. The Center City Connector tunnel, opened in 1984, further improved transit access to Market Street.

In 1952, Bandstand (later American Bandstand) debuted at Forty-Sixth Street and Market. Hosted by Dick Clark, the show, featuring teenagers dancing to popular music, gained a national audience and broadcast Market Street and Philadelphia into American homes until its move to Los Angeles in 1964. Drexel and the University of Pennsylvania continued to expand their campuses around Market Street in the 1990s and 2000s.

However, post-war suburbanization and retail shifts led to the decline of Market Street’s traditional department stores. Snellenburg’s, Frank and Seder, and Lit Brothers closed by the late 1960s. Gimbel’s moved to the Gallery Mall in 1977, and its original building was demolished in 1979. Wanamaker’s was acquired in 1978, and Strawbridge & Clothier closed in 1996. In the 1970s, Old City’s manufacturing decline led to artists transforming factory spaces into lofts near Market Street, and by the early 1990s, restaurants, bars, and clubs revitalized the area. In the mid-2010s, the Philadelphia Inquirer and Philadelphia Daily News moved to the former Strawbridge’s building, with Century 21 reopening the ground floors in 2014.

In the 2010s, Market Street continued to see new developments and remained central to city life, hosting parades and marking the boundary between north and south Philadelphia. Despite dramatic changes over centuries, Market Street’s fundamental importance to Philadelphia’s economy, social fabric, and transportation remained constant, a testament to William Penn’s visionary city plan and the enduring spirit of Philadelphia.

Stephen Nepa, historian and educator

Related Topics: History of Philadelphia, Urban Development, American Commerce, Transportation History

Further Reading:

- Jackson, Joseph. America’s Most Historic Highway, Market Street, Philadelphia

- Weigley, Russell ed. Philadelphia: A 300-Year History

Image Credits: Library of Congress, PhillyHistory.org, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Digital Collections, New York Public Library, Library Company of Philadelphia, Rutgers University.