Fleet Street, England, synonymous with the roar of the printing presses and the heart of British journalism for centuries, holds countless stories within its storied streets. Among these tales are those whispered in the dimly lit corners of its historic pubs, havens for writers, thinkers, and everyday Londoners alike. The Tipperary, a charming pub nestled on Fleet Street, proudly proclaims its venerable age, even hinting at being the oldest pub in London. Yet, scratch beneath the surface of the romanticized narratives presented on its noticeboards and scattered across the internet, and a far more complex and fascinating truth emerges. This is the real story of The Tipperary, a Fleet Street institution whose authentic history is far more compelling than the fabricated legends that have come to obscure it.

Let’s start by addressing the inaccuracies propagated by the noticeboard that greets visitors to this inviting, albeit compact, Fleet Street establishment. With its mosaic floor adorned with shamrocks and walls lined with dark wood panels, The Tipperary exudes an old-world charm. However, the historical claims presented to patrons, while aiming to enhance this atmosphere, unfortunately stray far from the factual record. These inaccuracies, riddled with errors in grammar and spelling – a point of irony considering Fleet Street’s journalistic heritage – are not just minor missteps; they represent a significant distortion of the pub’s rich past.

The noticeboard asserts: “The pub was built on the side of a monastery which dated to 1300 where, amongst other duties, the monks brewed ale.” This statement conflates several historical details and presents them incorrectly. Firstly, it was not a monastery but a friary, specifically belonging to the Carmelite order, or “white friars.” These were friars, not monks. The Carmelite house was established in Fleet Street around 1241 by Sir Richard Gray, predating the claimed 1300 date. The Carmelites, originating in the 12th century and named after Mount Carmel in Israel, were indeed known to brew ale, but their establishment was a friary, a different type of religious house from a monastery. It’s worth noting that just across the River Fleet, the Dominican friars, known as “black friars,” had their base, their legacy preserved in the name of the Blackfriars Bridge and the stunning art nouveau Black Friar pub.

The noticeboard further claims: “This site was an island between the River Thames and the River Fleet which still runs under the pub that is now little more than a stream”. This is geographically inaccurate. The Tipperary stands partway up the slope rising from what was once the western bank of the River Fleet. The river itself flowed approximately 250 yards to the east, certainly not beneath the pub. The Fleet, now largely subterranean and functioning as a sewer, flows south along the path of modern-day Farringdon Street, eventually joining the Thames under Blackfriars Bridge. The notion of The Tipperary being on an “island” between the two rivers is simply unfounded.

Tipperary Pub Exterior Fleet Street London

Tipperary Pub Exterior Fleet Street London

The Tipperary, 66 Fleet Street, a cherished landmark amongst Fleet Street’s historical pubs.

Another claim on the noticeboard reads: “‘The Boars Head’ which was built in 1605”. While the pub is indeed historically known as the Boar’s Head, the 1605 construction date is incorrect. In fact, the Boar’s Head is significantly older. Records from 1443, in a grant to the Carmelite friars, mention “Le boreshede in Parish of St Dunstan in Fletestrete,” alongside the Bolt and Tun inn next door. This places the Boar’s Head’s origins in the mid-15th century, making it at least 575 years old. This antiquity places it among a select few London pubs with such a lengthy history. Interestingly, in this instance, the pub’s claim errs on the side of being younger than its actual age, a rare form of historical understatement.

The noticeboard continues: “It survived the Great Fire of London in 1666. This is because the property was of stone and brick whereas the surrounding neighbouring premises were of wood.” This assertion is also historically inaccurate. The Great Fire of 1666 devastated a vast swathe of London, including Fleet Street, reaching just beyond Fetter Lane, approximately 160 yards west of The Tipperary/Boar’s Head. The Boar’s Head, like thousands of other buildings in the area, was consumed by the fire. While it’s true that some post-fire rebuilding incorporated stone and brick more extensively, the claim that the Boar’s Head survived due to its construction material is false.

The noticeboard then states: “In approx 1700 the S.G. Mooney & Son brewery chain of Dublin purchased ‘The Boars Head’ and it became the first Irish pub outside Ireland … The pub also became the first pub outside Ireland to have bottled Guinness and later draft.” This claim is riddled with inaccuracies. Firstly, the brewery chain was not “S.G. Mooney & Son” but J.G. Mooney & Co. A beautiful, antique mirror inside the pub correctly displays the name “J G Mooney and Co,” making the error on the noticeboard even more perplexing. James G. Mooney operated a licensed wholesale and retail business in Dublin from at least 1863, which evolved into the pub chain. Secondly, The Tipperary was definitively not “the first Irish pub outside Ireland.” J.G. Mooney & Co. had already established pubs in London, starting with one on the Strand in 1889, followed by locations on High Holborn in 1892 and Duke Street near London Bridge shortly after. Mooney’s acquired the Boar’s Head lease in November 1895, making it their fourth London pub, not their first outside of Ireland. The “approx 1700” date is almost two centuries off. Furthermore, Guinness was exported to Bristol as early as 1825, and even earlier to the West Indies, both in bottles and casks, debunking the claim that the Boar’s Head was the first pub outside Ireland to serve bottled or draught Guinness.

Tipperary Pub Mooney Mirror

Tipperary Pub Mooney Mirror

An elegant mirror inside The Tipperary, showcasing the correct name of the former owners, JG Mooney & Co., contradicting the inaccurate signboard.

Finally, the noticeboard claims: “1918 At the end of the Great War the printers who came back from the war had the pubs name changed to ‘The Tipperary” from the song ‘It’s a Long Way’, which name it retains to this day.” This is another fabrication. While the pub was referred to as “Mooney’s Irish House (late Boar’s Head)” in 1895, and Kelly’s directories confirm its name as The Irish House until 1967, the name change to The Tipperary occurred much later, around 1967. There is no evidence to suggest the pub was known as The Tipperary before this time; it was consistently referred to as “Mooney’s Irish House in Fleet Street” throughout the 1950s. Interestingly, there is a Fleet Street connection to the song “It’s a Long, Long Way to Tipperary,” but it has nothing to do with returning printers renaming the pub. A Daily Mail reporter, George Curnock, observed British soldiers singing the song in France in August 1914 and cabled his news editor, Walter Fish. Fish, recognizing the song’s potential as a patriotic anthem, promoted it in the Daily Mail, and it quickly gained widespread popularity.

These multiple inaccuracies on the noticeboard highlight a significant distortion of The Tipperary’s true history. Correcting these errors requires some research, but it is by no means an insurmountable task. A few hours of online investigation and archival research can reveal a far more accurate and compelling narrative. It underscores the importance of critical thinking and independent research, rather than simply accepting and repeating readily available but potentially flawed information.

To uncover the genuine history of 66 Fleet Street, we need to delve deeper into its past, starting with its earlier names and associations. Originally, the Boar’s Head faced Whitefriars Street (formerly Water Lane, named after the Carmelite friars). To its south was the Bolt-in-Tun inn. Both properties had back entrances onto Fleet Street, which later became numbers 64 and 66. To the east, at what became 67 Fleet Street, was the Cock and Key tavern. A 1443 license granted to the Carmelite Friars mentions “Hospitium vocatum le Boltenton” as a boundary, indicating a guest house associated with the friary. This hospitium, or a building on its site, likely predates 1443, as evidence suggests Fleet Street was already well-populated by 1353.

The Bolt-in-Tun’s name is a pun on “Bolton,” and its sign featured a bolt through a tun (cask). The origin of the name remains uncertain. Some incorrect sources link it to Prior William Bolton of St. Bartholomew, Smithfield, but Prior Bolton, born around 1450, lived after the inn’s first known mention. It’s more probable that Prior Bolton adopted the bolt-in-tun as his badge from the Carmelite inn.

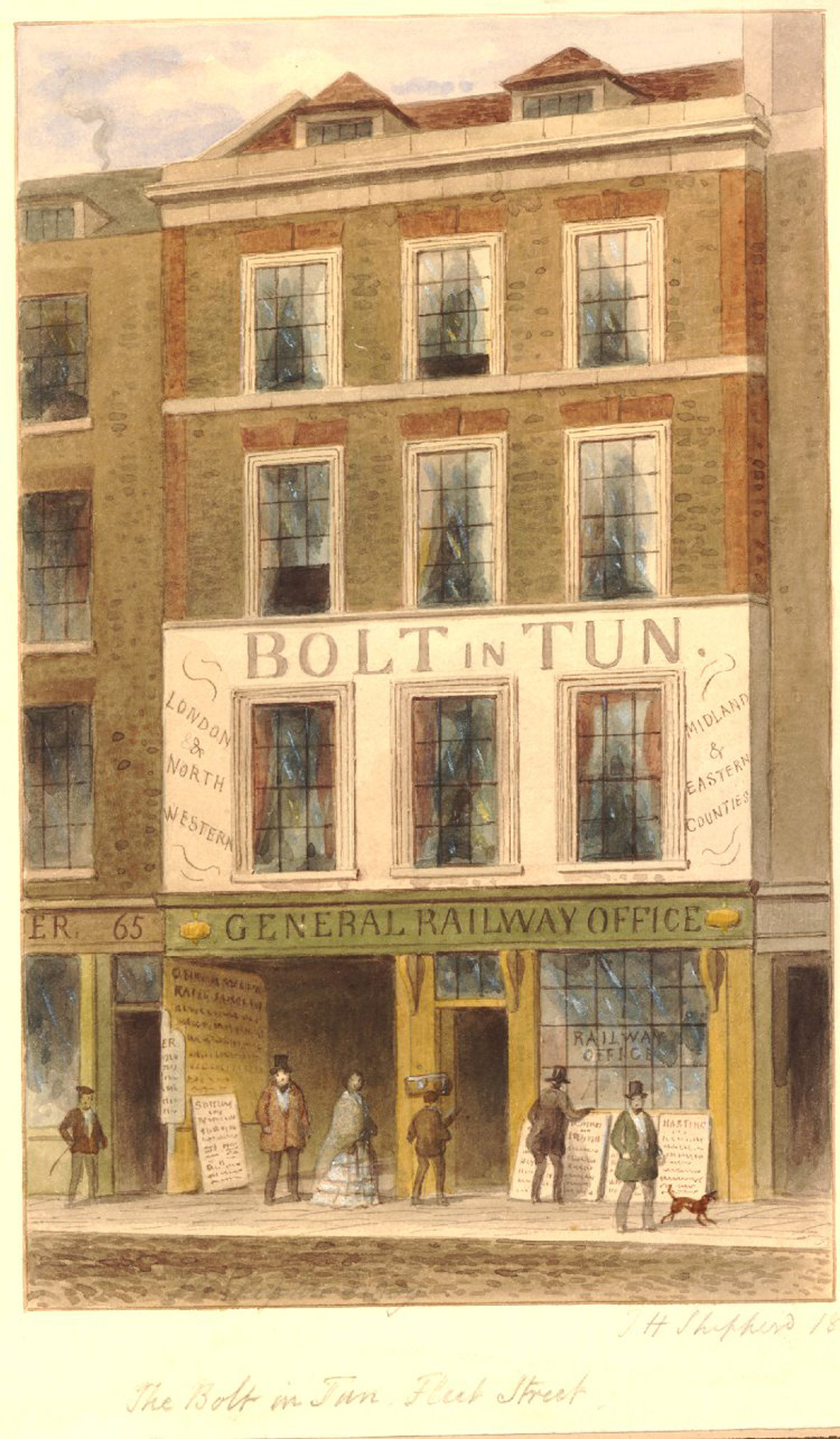

Bolt in Tun Fleet Street 1859

Bolt in Tun Fleet Street 1859

The Bolt in Tun, 64 Fleet Street, in 1859, repurposed as a railway booking office, a far cry from its coaching inn heyday. Note the bolt and tun symbols on the facade.

The Carmelites likely used the Bolt-in-Tun for brewing. After Henry VIII dissolved their friary in 1538, records listed “a tenement for brewing called ‘le Bolte and Tunne’” and “a brewhouse called Le Bolt and Tunne” as belonging to the former friars. In 1541, this brewhouse was leased to John Gilman, a royal household official. As Fleet Street’s first inn on the Great West Road, the Bolt-in-Tun became a vital coaching hub for routes to Bristol, Plymouth, and South Wales. In 1665, a boy died of the Plague in its hayloft, a grim reminder of the era. The Great Fire of London in 1666, while devastating, helped to curb the plague. By 1704, coaches to Windsor operated from the rebuilt inn, and by 1741, services included luxurious “Glass Coaches” to Bath. In 1805, the Bolt-in-Tun served destinations from Cardiff to Hastings, and in 1817, 26 daily coaches departed from the inn.

Around 1822, the Whitefriars Street side became the Sussex Hotel, but the Bolt in Tun continued on Fleet Street as a booking office and coach terminus, still serving drinks. In 1830, a man was arrested in the Bolt-in-Tun tap for stealing a horse blanket from its stables, claiming he was “very tipsy.” A fire in the hayloft in 1838 caused significant damage. Robert Gray, the coaching operations proprietor, partnered with Moses Pickwick – a name that Charles Dickens, a Fleet Street reporter, famously adopted for his novel.

The coaching era waned with the rise of railways. By the 1840s, the Bolt-in-Tun was advertised as a “Mail, Coach, and Railway Establishment.” Railways eventually dominated, and by 1859, the Bolt-in-Tun primarily functioned as a railway booking office and parcel depot. In the early 1880s, most of the Bolt-in-Tun was demolished, ending over 440 years of history.

In their 1973 book, City of London Pubs, Timothy Richards and James Stevens Curl mistakenly conflated the Bolt-in-Tun and The Tipperary, incorrectly stating that Mooney’s built a new pub on the Bolt-in-Tun site after 1883. This is demonstrably false, highlighting that even respected historians can sometimes err.

The Boar’s Head, in contrast to its bustling neighbor, led a quieter existence. Boar’s Head Alley, adjacent to the pub, is first recorded in 1570. In 1595, alley residents were cited for chimney issues. William Hayley or Healey was the first known licensee in 1664-1665. The pub was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666, but Hayley rebuilt it, issuing a trade token in 1668. The exact extent of the post-fire rebuilding remains unclear, but the City of London’s 2016 “Fleet Street Conservation Area Character Summary and Management Strategy” identifies it as one of the few “immediately post-Great Fire” survivors in the area, dating the current building to “circa 1667,” noting its “crooked window details” and “traditional pub frontage.”

In the 17th century, the area behind the Boar’s Head, known as “Alsatia,” retained sanctuary privileges from its Carmelite friary past, reinforced by a 1608 royal charter. Alsatia became a refuge for debtors and outlaws until these privileges were revoked in 1697.

The area remained lively. In 1716, a Jacobite mob attacked the Boar’s Head during the “mug house” riots because the landlord, Mr. Gosling, supported King George. While the Boar’s Head, described as an “ale house,” escaped major damage, the mob targeted Mrs. Read’s Coffee House nearby, a Whig stronghold. The riots escalated, resulting in deaths and arrests, highlighting the turbulent political climate of the time.

Shamrock Tiles Tipperary Pub Floor

Shamrock Tiles Tipperary Pub Floor

The charming shamrock mosaic floor at The Tipperary, a testament to its Irish pub heritage.

The Boar’s Head, under landlord Gosling, featured in Ned Ward’s A Vade Mecum for Malt Worms (c. 1716), making The Tipperary one of the few pubs from Ward’s guide still operating. Ward praised Gosling as “justly prais’d/and by his Courage and good Drink emblaz’d.”

However, a later landlady faced criticism. In 1775, Sarah Fortescue, the Boar’s Head’s victualler, was reprimanded for keeping late hours and hosting “lewd women and other infamous and disorderly persons.”

By 1812, the Boar’s Head had elevated its status, being described as a “first rate Wine Vault and Liquor Shop.” It survived the demolition of the Bolt-in-Tun and in 1895 became the fourth Mooney’s Irish House in London, following the death of J.G. Mooney. His sons, Gerald and John Joseph, continued the business. They commissioned architect R.L. Cox to refurbish the pub, likely responsible for the mosaic floor and the “Mooney’s” doorstep. Mooney’s expanded to eleven London pubs, known for Irish staff, excellent service, prices, and food.

In the 1960s, Mooney’s began to withdraw from London. The former Boar’s Head was sold around 1966-67, and renamed The Tipperary. The Boar’s Head name was possibly revived for an upstairs dining area. Greene King may have taken over in the 1960s, though evidence suggests otherwise until later. The pub closed for refurbishment around 1980 and was a Greene King pub by 1986. Greene King later sold it, and it is now independently owned.

This detailed account provides a far more accurate history of The Tipperary, a Fleet Street landmark, than the misleading information commonly circulated. However, changing ingrained misconceptions is challenging. Numerous books, articles, and websites perpetuate the inaccurate version, highlighting the persistence of misinformation.

Tipperary Pub Sign Claim

Tipperary Pub Sign Claim

The misleading signboard outside The Tipperary, perpetuating historical inaccuracies.

The true story of The Tipperary is a testament to Fleet Street’s rich history, a story far more compelling than any fabricated myth. It stands as a reminder that even in the age of instant information, diligent research and critical evaluation are crucial for uncovering the real stories behind our historical landmarks.