Greenwood, Tulsa, Oklahoma, was once a shining beacon of African American prosperity and entrepreneurship, so much so that it earned the moniker “Black Wall Street.” This thriving district, built on Black excellence and self-sufficiency, was tragically reduced to ashes in a violent episode known as the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921. This horrific event, often considered the single worst incident of racial violence in American history, saw the destruction of over a thousand homes and businesses and resulted in credible estimates of deaths ranging from fifty to three hundred. The Tulsa Race Massacre remains a stark reminder of the racial tensions of the era and the fragility of Black wealth in the face of systemic racism.

The Tulsa Race Massacre was not an isolated incident but occurred during a period of intense racial strife across the United States. This era witnessed the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and a nationwide increase in racial violence, particularly targeting African American communities. Black communities across the country actively resisted these attacks, most notably in the face of rampant lynchings. These national trends were acutely mirrored in Oklahoma and Tulsa, setting a volatile stage for the events of 1921.

By 1921, Tulsa was a burgeoning city fueled by the oil boom, boasting a population exceeding one hundred thousand. Within this city, the Greenwood District stood as a testament to Black achievement. Home to approximately ten thousand African Americans, Greenwood was a vibrant hub of commerce and culture. It featured two newspapers that amplified Black voices, numerous churches that served as community anchors, a library branch fostering knowledge, and a multitude of Black-owned businesses that fueled economic independence. This self-contained and prosperous community was the embodiment of “Black Wall Street,” a place where Black Americans thrived despite the pervasive racial segregation of the time.

However, beneath the veneer of prosperity, Tulsa was also a city grappling with significant social problems. Crime rates were alarmingly high, and vigilantism was rampant. Just months before the massacre, in August 1920, a white teenager accused of murder was lynched by a white mob. Disturbingly, newspaper accounts at the time indicated that the Tulsa police offered little resistance to the lynching, failing to protect the victim who was forcibly removed from his jail cell at the county courthouse. This environment of lawlessness and racial prejudice foreshadowed the even greater tragedy to come.

Eight months later, a fateful encounter involving Dick Rowland, a young African American shoeshiner, and Sarah Page, a white elevator operator, ignited the spark that would engulf Greenwood. The precise details of what transpired in the Drexel Building on May 30, 1921, remain debated. The most widely accepted account suggests that Rowland accidentally stepped on Page’s foot as he entered the elevator, causing her to scream, possibly out of surprise or fear.

However, the following day, the Tulsa Tribune, Tulsa’s afternoon newspaper, published a sensationalized report alleging that Rowland, who had been arrested, had attempted to rape Page. Adding fuel to the fire, eyewitness accounts suggest that the Tribune also printed a now-missing editorial titled “To Lynch Negro Tonight,” explicitly inciting racial violence. By the early evening of May 31st, the atmosphere in Tulsa was thick with racial animosity, and the threat of lynching once again hung heavy in the air.

A photograph capturing the extensive damage inflicted during the Tulsa Race Massacre, highlighting the destruction of buildings and infrastructure.

A photograph capturing the extensive damage inflicted during the Tulsa Race Massacre, highlighting the destruction of buildings and infrastructure.

The inflammatory rhetoric quickly translated into action. By 7:30 p.m., a large crowd of white Tulsans had gathered outside the Tulsa County Courthouse, their demands focused on the immediate handover of Dick Rowland for lynching. Sheriff Willard McCullough, to his credit, refused to yield to the mob’s demands. Around 9 p.m., news of the escalating tension downtown reached Greenwood. Responding to the threat, a group of approximately twenty-five armed African American men, many of them veterans of World War I who had bravely served their country, traveled to the courthouse. They offered their assistance to the sheriff to protect Rowland from the lynch mob. Sheriff McCullough, however, declined their offer, and the men returned to Greenwood.

The white mob, emboldened by the sheriff’s refusal of Black assistance and fueled by racial hatred, then attempted to breach the National Guard armory, seeking weapons. They were turned away by a small contingent of local guardsmen. Around 10 p.m., a false rumor swept through Greenwood, claiming that whites were already storming the courthouse. This misinformation prompted a second, larger group of African American men, perhaps seventy-five in number, to return to the courthouse, again offering their support to the authorities. Once more, they were turned away. As they were departing, a confrontation erupted when a white man attempted to disarm a Black veteran. In the ensuing struggle, a shot rang out. This single gunshot was the catalyst that unleashed the Tulsa Race Massacre.

Over the next eighteen hours, Tulsa descended into unimaginable chaos. The white mob, thwarted in their attempt to lynch Dick Rowland, redirected their fury towards the entire African American community of Greenwood, the “Black Wall Street.” Fierce fighting broke out along the Frisco railroad tracks, where Black residents valiantly defended their community against the encroaching mob. In downtown Tulsa, an unarmed African American man was brutally murdered inside a movie theater. Armed white individuals in cars began conducting “drive-by” shootings in Black residential areas, terrorizing families in their homes. By midnight, fires had been deliberately set on the fringes of the African American commercial district, the heart of Black Wall Street. In the city’s all-night cafes, white men openly organized and planned a full-scale invasion of Greenwood at dawn.

In the initial hours of the escalating crisis, local authorities were woefully inadequate in their response, effectively failing to contain the violence. Disturbingly, shortly after the gunfire erupted at the courthouse, Tulsa police officers actively deputized men who had been part of the lynch mob. According to a chilling eyewitness account, these newly deputized men were instructed by law enforcement to “get a gun and get a nigger,” effectively sanctioning and encouraging the violence. Local units of the National Guard were mobilized, but their actions were largely directed towards protecting a white neighborhood from a nonexistent Black counterattack, further abandoning Greenwood to its fate.

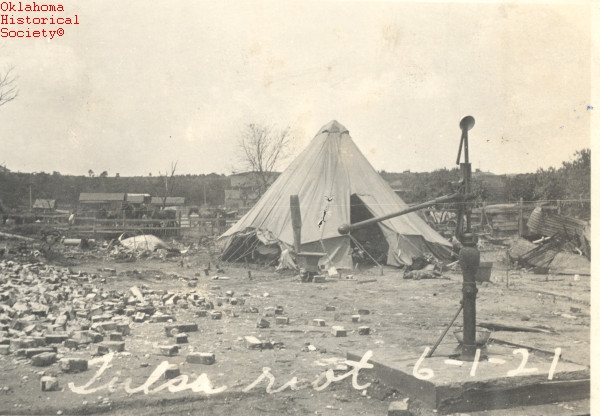

A poignant image depicting victims of the Tulsa Race Massacre residing in tents, highlighting the immediate aftermath of the destruction and displacement.

A poignant image depicting victims of the Tulsa Race Massacre residing in tents, highlighting the immediate aftermath of the destruction and displacement.

As dawn approached on June 1, thousands of armed white individuals amassed along the borders of Greenwood. With the first light of day, they surged into the African American district, unleashing a wave of looting, arson, and murder. Homes and businesses, the tangible symbols of Black Wall Street’s prosperity, were systematically ransacked and set ablaze. Numerous atrocities were committed, including the tragic murder of Dr. A.C. Jackson, a renowned Black surgeon, who was shot dead even after surrendering to a group of white attackers. Eyewitness testimonies and historical accounts suggest that the white mob utilized at least one machine gun in their assault, and some survivors claimed that airplanes were used to drop incendiary devices on Greenwood, though this remains debated.

The residents of Greenwood, despite being outgunned and outnumbered, mounted a courageous defense of their homes and businesses. Particularly intense fighting occurred around Standpipe Hill. However, the overwhelming force of the white mob, combined with the complicity and inaction of local authorities, proved insurmountable. By the time additional National Guard troops finally arrived in Tulsa at approximately 9:15 a.m. on June 1, the once-thriving Black Wall Street of Greenwood was largely reduced to smoldering ruins.

In the immediate aftermath of the massacre, Tulsa was placed under martial law, a stark acknowledgment of the city’s complete breakdown of order. A period of recriminations and legal maneuvering followed, but justice remained elusive for the victims of Greenwood. Despite Dick Rowland being exonerated of any wrongdoing, an all-white grand jury, predictably biased, placed the blame for the violence squarely on the African American community. Despite overwhelming evidence of white culpability in the murders and arson, not a single white person was ever convicted or imprisoned for the crimes committed during the Tulsa Race Massacre.

Victims of the Tulsa Race Massacre sifting through the debris of their homes, searching for any salvageable possessions amidst the ruins of Greenwood.

Victims of the Tulsa Race Massacre sifting through the debris of their homes, searching for any salvageable possessions amidst the ruins of Greenwood.

The Tulsa Race Massacre left the vast majority of Greenwood’s African American population homeless and destitute. Despite facing immense hardship and the overt desire of the white establishment to prevent the rebuilding of Greenwood and force the relocation of the Black community, the spirit of Black Wall Street persisted. Within days of the devastation, Black Tulsans began the arduous process of rebuilding their lives and their community. However, thousands were forced to endure the harsh winter of 1921–22 living in tents, a stark symbol of the immense loss and displacement they had suffered.

The deep wounds inflicted by the Tulsa Race Massacre remained unhealed for generations. While Greenwood was eventually rebuilt, the scars of the tragedy, both physical and emotional, endured. Many families never fully recovered from the economic and personal losses. For decades, the Tulsa Race Massacre became a taboo subject, shrouded in silence and omitted from mainstream historical narratives, particularly within Tulsa itself. In 1997, a state commission was finally formed to investigate the historical events and their lasting impact. The commission’s report recommended that reparations be paid to the remaining Black survivors and their descendants as a form of restorative justice. Subsequent archaeological investigations by scientists and historians have uncovered evidence supporting long-held beliefs that unidentified victims of the massacre were buried in unmarked mass graves, further underscoring the scale of the tragedy and the need for remembrance and reconciliation.

The Tulsa Race Massacre, the destruction of Black Wall Street, stands as a profound tragedy in American history, a potent symbol of the systemic racism and violence that African Americans have faced. It is a crucial reminder of the ongoing struggle for racial justice and equality in the United States and the importance of acknowledging and learning from the darkest chapters of our past to build a more equitable future. The story of Black Wall Street and its destruction serves as both a cautionary tale and an inspiration, highlighting the resilience and determination of the Black community in the face of unimaginable adversity.

See Also

AFRICAN AMERICANS, CHARLES FRANKLIN BARRETT, GREENWOOD DISTRICT, KU KLUX KLAN, LYNCHING, NEWSPAPERS–AFRICAN AMERICAN, OKLAHOMA NATIONAL GUARD, JAMES BROOKS AYERS ROBERTSON, SEGREGATION, ANDREW J. SMITHERMAN, TULSA, TULSA TRIBUNE, TWENTIETH-CENTURY OKLAHOMA

Browse By Topic

Explore

Learn More

version=”1.0″?Scott Ellsworth, Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1982).

John Hope Franklin and Scott Ellsworth, eds., The Tulsa Race Riot: A Scientific, Historical and Legal Analysis (Oklahoma City: Tulsa Race Riot Commission, 2000).

Eddie Faye Gates, They Came Searching: How Blacks Sought the Promised Land in Tulsa (Austin, Tex.: Eakin Press, 1997).

Loren L. Gill, “The Tulsa Race Riot” (M.A. thesis, University of Tulsa, 1946).

Robert N. Hower, “Angels of Mercy”: The American Red Cross and the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot (Tulsa, Okla.: Homestead Press, 1993).

Mary E. Jones Parrish, Events of the Tulsa Disaster (Tulsa, Okla.: Out on a Limb Publishing, 1998).

Related Resources

100 Block North Greenwood Avenue, National Register of Historic Places

Vernon A.M.E. Church, National Register of Historic Places

Tulsa Race Riot Report (PDF), Oklahoma Historical Society

Interview with Otis Clark, Voices of Oklahoma

Interview with Wess and Cathryn Young, Voices of Oklahoma

Citation

The following (as per The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition) is the preferred citation for articles:Scott Ellsworth, “Tulsa Race Massacre,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=TU013.

Published January 15, 2010 version=”1.0″? Last updated July 29, 2024

© Oklahoma Historical Society