Bruce Springsteen’s “Incident on 57th Street” wasn’t just recorded on his 24th birthday; it was a birth of sorts itself – the emergence of a songwriting titan. Let that fact resonate as you listen to what many consider his first true masterpiece of storytelling in song.

Often, when dissecting a song, there’s a specific angle or element to focus on – lyrics, melody, historical context. However, with “Incident on 57th Street,” the entire composition is the hook.

The brilliance of “Incident on 57th Street” lies in its perfection across every facet. The lyrics mark a pivotal moment where Springsteen seamlessly blended vivid imagery with a compelling narrative – a balance he hadn’t quite achieved before. The music is equally crucial, with each band member and instrument contributing to the unfolding story as much as Springsteen’s evocative vocals. The arrangement remains timeless, devoid of any dated feel even decades later.

Poll any group of Springsteen devotees for their top songs, and you’ll encounter a diverse range of favorites. Yet, “Incident on 57th Street” consistently ranks high, a testament to its enduring power.

Springsteen had previously explored epic storytelling, with songs like “Lost in the Flood” hinting at his potential. However, “Lost in the Flood,” while powerful, leans more towards a metaphorical street painting than a clearly defined story. Similarly, “New York City Serenade,” a thematic sibling from the same album, boasts grand orchestration but sometimes drifts into sentimentality. Earlier, pre-fame outtakes offered glimpses of his burgeoning talent, but lacked the cohesive impact of what was to come.

“Incident on 57th Street” marks the moment Springsteen crystallized his artistic vision. It served as a crucial stepping stone, paving the way for future epics like “Jungleland” (often seen as a thematic successor), “Backstreets,” and “Racing in the Street.”

Let’s delve into the heart of this masterpiece.

The introduction itself is iconic. Springsteen is renowned for crafting memorable song openings, but the overture of “Incident on 57th Street” is arguably his finest. David Sancious’s piano sets a scene, like opening a storybook with “Once upon a time…”. Danny Federici’s organ builds a sonic staircase, and Springsteen’s ethereal, guitar-bending invitation of “follow me” beckons us into the narrative.

Within the first twenty seconds, the song’s genius is already palpable.

When Vini Lopez’s drums bring in the full band, the individual instrumental threads from the introduction weave together in perfect synchronicity, grounded by Garry Tallent’s bass. (Garry’s bassline deserves special attention later, as it takes center stage in a crucial moment.)

Springsteen begins to unfold his tale:

Spanish Johnny drove in from the underworld last night

With bruised arms and broken rhythm in a beat-up old Buick but dressed just like dynamite

He tried sellin’ his heart to the hard girls over on Easy Street

But they sighed, “Johnny, it falls apart so easy and you know hearts these days are cheap”

Every word in this opening verse, and indeed throughout the entire song, is meticulously chosen and serves a purpose.

In just four lines, Johnny’s character is vividly drawn. He’s a hustler from the fringes, yet a romantic at heart. He might sell his body to wealthy clients, but his deeper desire is to offer genuine connection. However, the women of Easy Street, cynical and detached, dismiss his emotional offerings. Relationships are fleeting and transactional in their world; paying for services is simpler than emotional investment. (Notice how Springsteen’s vocal delivery subtly shifts to capture the jaded indifference of the Easy Street women).

Despite his sharp attire, Johnny’s life is far from easy. The “bruised arms” hint at heroin addiction, revealing where his earnings likely disappear, explaining his dilapidated Buick.

All this character development unfolds in just four lines. And Springsteen is just beginning. Johnny’s addiction brings him into conflict with his superiors:

And the pimps swung their axes and said, “Johnny, you’re a cheater”

Well, the pimps swung their axes and said, “Johnny, you’re a liar”

Again, Springsteen’s vocal control is masterful. He subtly embodies the accusatory tone of the pimps, then seamlessly reverts back to the narrator’s voice.

And from out of the shadows came a young girl’s voice

This is a pivotal narrative turn, underscored by Sancious’s three delicate piano flourishes.

Said, “Johnny, don’t cry”

Bruce’s vocal delivery here is gentle, tender, piquing our curiosity about the voice’s origin.

Puerto Rican Jane, oh, won’t you tell me what’s your name

I want to drive you down to the other side of town

Where paradise ain’t so crowded, there’ll be action goin’ down on Shanty Lane tonight

All them golden-heeled fairies in a real bitch fight pull thirty-eights and kiss the girls goodnight

The power of this passage is immense. Danny Federici’s organ (perhaps with Sancious joining in, creating a rich organ texture) swells, creating a sense of swirling motion as Johnny and Jane, the ill-fated lovers, find each other.

Johnny is instantly captivated by Jane (who we soon learn is also a sex worker). He proposes they escape Easy Street, where he’s in trouble with the “axe-swinging pimps,” and return to his side of town. He acknowledges the inherent dangers of his territory but implies it’s a safer haven for them now.

Then comes the first chorus, with Suki Lahav’s ethereal, double-tracked backing vocals adding a heavenly dimension:

Oh, goodnight, it’s alright, Jane

Now let them black boys in to light the soul aflame

We may find it out on the street tonight, baby

Or we may walk until the daylight, maybe

Here, we understand that Puerto Rican Jane, like Spanish Johnny, is also a sex worker. Johnny encourages her to join him in his territory, suggesting a clientele that might be more to her liking.

A brief but necessary digression on race and sexuality in “Incident on 57th Street.” It’s impossible to analyze the song without acknowledging these elements.

“Incident” centers on two Latino sex workers. While Springsteen doesn’t romanticize their profession, he imbues Johnny, particularly, with a swagger and self-assuredness, suggesting a degree of comfort with his identity and work. He also paints African-American clients in broad strokes, romanticizing them as sexually skilled enough to “light a streetwalker’s soul aflame.”

Looking back decades later, we can examine Springsteen’s language (always deliberate and purposeful) and consider whether he veered into stereotyping. However, this is arguably as close to that line as Springsteen ever comes, as he quickly shifts focus back to the intense connection between Johnny and Jane. Their shared profession becomes the backdrop for their burgeoning love, forged as they walk the streets together, seeking work, watching out for each other through the long night until dawn.

As the night ends, they find refuge – the exact location remains unspecified, unimportant. It’s simply a private space, a momentary sanctuary – her place, his, or somewhere in between. The story continues:

Well, like a cool Romeo he made his moves, ah, she looked so fine

And like a late Juliet she knew he’d never be true, but then she didn’t really mind

Upstairs a band was playin’, the singer was singin’ something about going home

She whispered, “Spanish Johnny, you can leave me tonight, but just don’t leave me alone”

Johnny is portrayed as the smooth talker, the charmer. But after a night spent navigating the streets and sharing intimacies, Jane understands men and Johnny well enough to know fidelity might be too much to expect. She accepts the transactional nature of their world, implicitly acknowledging she must share his body. Her plea, “don’t leave me alone,” is a deeper yearning for emotional constancy, for him to return to her emotionally, even if his physical fidelity is uncertain.

(The lyric “the singer was singin’ something about going home” is a stroke of genius. It seems like a throwaway detail, yet serves two crucial functions. First, it grounds the lovers in their immediate present, making background details fade into insignificance. Second, it acts as a subtle prompt for Jane’s whispered plea. This verse is a lyrical highlight.)

But the Romeo and Juliet allusion foreshadows tragedy. The listener senses this won’t end happily. Something is brewing.

Johnny confirms the impending danger:

And Johnny cried, “Puerto Rican Jane, word is down the cops have found the vein”

Well, them barefoot boys, they left their homes for the woods

Them little barefoot street boys, they said homes ain’t no good

They left the corners, threw away all of their switchblade knives

And kissed each other goodbye

The police have located the source of the local drug supply, and the street-level dealers scatter, leaving the streets eerily deserted – supply cut off, but demand inevitably rising.

This is where the song transcends brilliance and enters masterpiece territory.

The street is now empty, and Johnny is lost in thought, grappling with an unspoken dilemma. The E Street Band fades away, the soundscape mirroring the deserted street. In a rare and powerfully effective move, Garry Tallent’s bass takes over the melody, quiet and soft, accompanied only by Vini Lopez’s cymbal rolls, like tumbleweeds drifting through the emptiness.

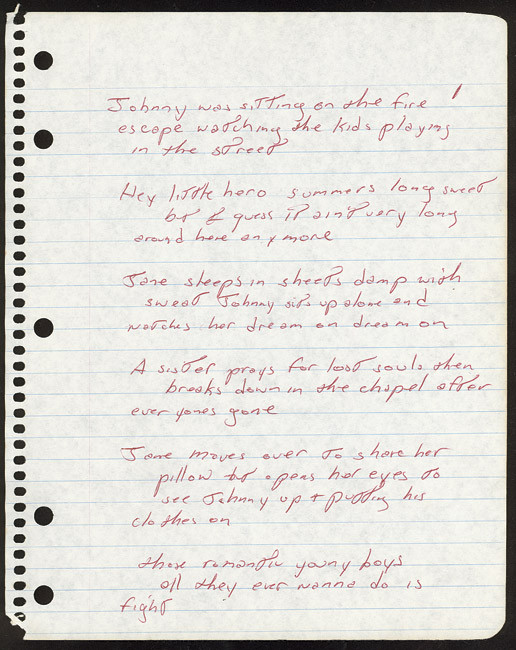

Johnny was sittin’ on the fire escape watchin’ the kids playin’ down in the street

He called down, “Hey, little heroes, summer’s long, but I guess it ain’t very sweet around here anymore”

Janey sleeps in sheets damp with sweat; Johnny sits up alone and watches her dream on, dream on

And the sister prays for lost souls, then breaks down in the chapel after everyone’s gone

Johnny might address the “little heroes” below (who are likely not children, their “play” less innocent than it seems), but he’s truly talking to himself. He’s consumed by inner turmoil, unable to sleep. The line about the sister praying for lost souls in the chapel is not throwaway; it’s foreshadowing, and Johnny’s awareness of it amplifies the sense of impending doom.

Jane moves over to share her pillow but opens her eyes to see Johnny up and putting his clothes on

She says, “Those romantic young boys, all they ever want to do is fight”

Those romantic young boys, they’re callin’ through the window:

“Hey, Spanish Johnny, you want to make a little easy money tonight?”

Again, layers of meaning unfold. Jane awakens from a dream and dismisses “romantic young boys” and their inclination to violence. Her tone, emphasized by Suki Lahav’s backing vocal, suggests she sees Johnny as different, apart from that impulsive youth.

This makes the subsequent call from the street, inviting Johnny to exploit the drug vacuum, all the more devastating. Even Garry and Vini’s instruments pause momentarily at the question before resuming, mirroring Jane’s sinking heart.

Johnny attempts to reassure Jane:

And Johnny whispered, “Goodnight, it’s all tight, Jane

I’ll meet you tomorrow night on Lover’s Lane

We may find it out on the street tonight, baby

Or we may walk until the daylight, maybe”

The “Lover’s Lane” reference is another lyrical masterstroke. On one level, it’s a cynical euphemism for the harsh street where they work. On another, it’s a genuine, tender nickname for the street where their love blossomed during a night of shared vulnerability. This subtle duality is a lyrical gem, often missed by casual listeners.

Jane doesn’t believe Johnny’s reassurances, and perhaps Johnny doesn’t believe them himself. He repeats his empty promises with increasing desperation, transforming from reassurance to plea to prayer. His voice wails, fading into the rising power of the church organ and choir, like a Greek chorus guiding us away from the unfolding violence. Johnny’s fate remains unstated, yet we feel it deeply. (Springsteen would employ this narrative technique repeatedly.)

Finally, as we are drawn further from the street’s chaos, we are left with Jane, alone and abandoned, waiting, as her music box (Sancious on piano) plays the story to its close, slowing, fading like Johnny’s life, until silence.

Wow. Just… wow.

With such meticulous craftsmanship, it’s no surprise Springsteen is equally deliberate about “Incident on 57th Street”‘s live arrangements. Early performances reveal some experimentation, or perhaps simply the distinct character of the original E Street Band.

Only one recording exists of the song performed live by the original E Street Band. Days after a January 29, 1974, Nashville show, Springsteen fired Vini Lopez. David Sancious left six months later. The following recording is therefore unique, the only documented performance of “Incident on 57th Street” with both Lopez and Sancious. Note the extended, ethereal intro, Lopez’s almost overpowering drumming (sometimes excessive, yet perfect in the third verse), Federici’s powerful organ (usually more restrained in this song), and, most strikingly, the unique ending.

[Listen to the 1974 recording – link to audio if possible]

The next bootlegged performance, seven months later, was significant. When the lights dimmed, the E Street Band took the stage accompanied by Suki Lahav, reprising her studio vocals and adding exquisite violin to a breathtaking new acoustic arrangement. This marked the debut of Springsteen’s stripped-down, acoustic “Incident on 57th Street.”

[Listen to the acoustic version with Suki Lahav – link to audio if possible]

Suki became a featured guest a month later, and “Incident” remained a setlist staple during her time with the band.

In February 1975, at the Main Point in Bryn Mawr, PA, Springsteen opened with “Incident.” This performance, captured and broadcast in pristine quality, is arguably the definitive Springsteen live performance. Bruce and Suki are mesmerizing, and the siren sound effect at the close is a perfect, organic touch, so seamlessly integrated that many believed it was real for years.

[Listen to the Main Point 1975 performance – link to audio if possible]

Video footage from the following night exists, though the audio isn’t as clear, it’s still worth watching:

[Link to YouTube video of Main Point performance if possible]

“Incident” remained a frequent highlight throughout the Born to Run, Lawsuit, and Chicken Scratch tours, into the early Darkness Tour era.

Then, it vanished. Between 1978 and 1999, “Incident” surfaced only once during the 1980 River Tour at Nassau Coliseum, in an arrangement similar to modern versions. Fortunately, this rare performance was professionally recorded and released on a European EP in 1986.

For nearly two decades, “Incident” was absent. Fans wondered if it would ever return. The delight was palpable when Springsteen and the E Street Band opened their final Reunion Tour show in Philadelphia with it, as potent and majestic as ever.

[Listen to the Reunion Tour Philadelphia performance – link to audio if possible]

“Incident” appeared a few more times on the Reunion Tour and subsequent holiday shows, but it was the Rising Tour that saw its more frequent return, with over a dozen performances. One early Rising Tour performance was a stunning solo piano rendition, professionally filmed and included on Springsteen’s Live in Barcelona video. Remarkably, this 2003 performance was European fans’ first live encounter with the song on their home continent.

Aside from brief Vote for Change and Seeger Sessions tours, “Incident on 57th Street” has been a part of every tour since. It remains a rarity, appearing only a few times per tour, and remains a sought-after song for many long-time fans.

To conclude, here’s a recent performance from the 2016 River Tour, transformed into the “Autobiography” tour. When Springsteen structured his setlists to highlight his best work, “Incident on 57th Street” rightfully became a nightly fixture.

[Listen to a recent live performance – link to audio if possible]

Incident on 57th Street Recorded: September 23, 1973

Released: The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle (1973)

First performed: October 13, 1973 (Washington, DC)

Last performed: January 22, 2017 (Perth, Australia)

Explore more of your favorite Bruce songs in our full index. New entries added weekly!