It might come as a surprise to many that Charleston’s iconic East Bay Street wasn’t always a street. In fact, its story begins as a humble public wharf, nestled against the Cooper River’s tidal mudflats. Far from the bustling thoroughfare we know today, its initial form was less than ideal for maritime activities, and the natural riverbank was constantly threatened by erosion. To solve these issues and bolster maritime commerce while protecting the burgeoning town, the Lords Proprietors of Carolina initiated a visionary public-private partnership. This collaboration set in motion a long-term project that would ultimately sculpt the expansive waterfront landscape we admire today, centered around what we now know as East Bay Street.

Today, East Bay Street stands as one of Charleston’s most picturesque and frequented avenues. It’s a vibrant hub brimming with diverse shops, acclaimed restaurants, and historically significant buildings, all contributing to the city’s undeniable charm. Running parallel to the Cooper River waterfront, for three centuries, East Bay Street served as the primary artery for the flow of goods and people, connecting the town to the once-bustling commercial wharves that extended into the river. However, much of this maritime infrastructure has vanished over time. A substantial strip of reclaimed land, averaging about an eighth of a mile in width, now separates the historic street from the water’s edge. This accumulated earth and the layers of human construction effectively obscure the street’s modest beginnings. Yet, just beneath the surface of our modern perception, tangible clues to its origins as a simple wharf remain.

The historic heart of East Bay Street, stretching from Market Street southward to the northern edge of the High Battery, took shape nearly 350 years ago, in the early days of the Carolina colony. Long before elaborate wooden wharves reached deep into the Cooper River to welcome ships laden with cargo, East Bay Street was simply an exposed riverbank. It existed just above the high-water line, marked by the daily ebb and flow of the tides. To truly grasp its original character and appreciate its remarkable journey to become the landscape we see today, we must journey back in time, picturing the Palmetto City in its earliest form.

Charleston Time Machine · Episode 180: The Genesis of East Bay Street: Charleston’s First Wharf, 1680–1696

Initially, the peninsula nestled between the Ashley and Cooper Rivers was dubbed Oyster Point by the first European colonists of Carolina. In 1670, they established their capital, Charles Town, at Albemarle Point (now the Charles Towne Landing State Historic Site). While the main settlement was at Albemarle Point, a few individuals ventured to Oyster Point in the early 1670s. The colonial government recognized the peninsula’s potential as a convenient townsite. By the summer of 1672, the governor commissioned the colony’s surveyor general to create a town plan for Oyster Point and to physically mark it out on the land. This plan, known as the “Grand Model,” divided the southern part of the peninsula into slightly over three hundred building lots and eleven streets. The easternmost of these streets, running alongside and parallel to the Cooper River, is the area we now recognize as East Bay Street, though it wasn’t officially named for many years.[1]

Alt text: The Grand Model plan of Charleston, circa 1672, showcasing the early street grid including the future East Bay Street along the Cooper River waterfront.

In the spring of 1680, South Carolina’s provincial government relocated from Albemarle Point to the burgeoning town at Oyster Point. This marked the official renaming of the settlement to “Charles Town” (now Charleston). A rare glimpse into the town at this pivotal moment comes from a letter penned in May 1680 by Maurice Mathews, a resident of the town. Referring to the urban design of the Grand Model, Mathews highlighted that “new” Charles Town featured a structured grid of wide streets and spacious building plots. The provincial government was actively granting town lots to settlers who pledged to build upon them within a set timeframe. Along the waterfront, Mathews noted, “there is laid out 60 foot for a publick wharfe.” This reveals that the easternmost street, which would evolve into East Bay Street, was not initially conceived as a street in the traditional sense. It was intentionally designated as a public wharf, intended to facilitate the commercial shipping that was destined to become Charleston’s defining characteristic.

Mathews further described the waterfront area immediately east of this “publick wharfe” as “a clean landing the whole length of the town.” He assured that ships anchoring off the town would be safe in any weather, “for no wind can blow so great . . . as to hurt a vessell [sic] upon the soft sand or oaze [ooze].” At the southern tip of the peninsula, Mathews observed, “ships may also grate upon the point [White Point] with much ease and safety.” Therefore, at Charleston’s founding, its entire eastern waterfront was naturally bordered by a vast mudflat, free of hazardous rocks or obstructions.[2]

Charles Town and its maritime activity experienced rapid growth after the capital’s move to the peninsula in 1680. Shipping was the lifeblood of the fledgling colony, forging vital connections between South Carolina and distant ports in England and the Caribbean. However, detailed accounts of life in the new capital during the 1680s are scarce, making it challenging for modern Charlestonians to envision the original condition of the town’s eastern waterfront along the Cooper River. Fortunately, the recent discovery of a hand-drawn map of Charleston, believed to be created around 1686 by French immigrant Jean Boyd, offers a valuable visual representation of the small town. At this time, settlement was primarily concentrated near the Cooper River and south of Broad Street (as discussed in Episode No. 98).

Today, we recognize East Bay Street as a landlocked thoroughfare, separated from the Cooper River’s waters. To truly visualize this historic street in its original form – a long, narrow wharf and the epicenter of early South Carolina commerce – we must engage our imaginations. Supplementing this with an understanding of maritime practices, we can construct a mental image of Charleston’s first wharf and the logistics of its early commercial operations.

Alt text: Aerial view of modern East Bay Street in Charleston, South Carolina, highlighted with a yellow dotted line to show its present-day route and separation from the Cooper River.

Let’s begin by considering the natural topography of this low-lying coastal environment. Forget the brief, inaccurate waterfront scene from the 2000 film The Patriot, which depicted large ships docked directly alongside East Bay Street. Charleston’s original waterfront was not a deep-water port. Large sailing vessels never moored alongside it for loading and unloading because the shallow waters simply didn’t allow it. All the land immediately east of the wharf, now East Bay Street, was once a sloping mudflat, exposed at low tide and largely submerged at high tide. Like other intertidal mudflats along South Carolina’s coastal rivers, this quayside area was likely covered in a vibrant carpet of cordgrass or spartina (now Sporobolus alterniflorous). While modern Charleston extends much further into the rivers than it did centuries ago, this resilient cordgrass still thrives along the tidal edges of the Ashley and Cooper Rivers.[3]

Charleston’s original wharf, therefore, was essentially a long, narrow bank marking the high-water line, bordering the Cooper River’s tidal mudflat. So, how did the town’s early settlers manage to transport cargo across this muddy terrain between ships and the shore? Before the early 18th century, when investors began constructing wooden piers extending eastward into the river, Charlestonians relied on traditional maritime practices common worldwide. Small sailing vessels and rowboats, particularly canoes, periaugers, and small schooners carrying goods from nearby plantations, could anchor close to the wharf at high tide and then settle amongst the cordgrass at low tide. Crews could then form human chains, standing in the pluff mud to hand cargo up to the wharf.

However, this simple method was unsuitable for larger sailing vessels, which needed deeper anchorage of at least 18–24 feet. In Charleston’s early years, such depths were found roughly 600 to 1,000 feet east of the wharf we now call East Bay Street. To bridge this gap, mariners employed smaller boats to ferry cargo between ship and shore. Detailed descriptions of this logistical process are lacking in early South Carolina’s sparse records, but it was an age-old practice in port communities globally. Shallow-draft, flat-bottomed barges, known as “lighters” in England, would float alongside larger vessels to receive cargo, ballast, or passengers. They would then be rowed to shore for unloading at, or near, the wharf. The use of lighters must have been so commonplace in early Charleston that it went largely undocumented, although government records do mention lighters transporting ballast within the harbor in the early 18th century.[4]

The transformation of Charleston’s initial wharf into the East Bay Street thoroughfare was a gradual process, driven by both human engineering and natural accumulation. Formal efforts began in the late 1690s, but discussions about the need to reinforce, “wharf-in,” or otherwise protect the town’s waterfront wharf had started in the late 1680s. Unsurprisingly, the earliest recorded discussions followed a hurricane. In August 1686, a Spanish invasion force from St. Augustine raided settlements across Port Royal, Edisto, and Wadmalaw Islands. However, a sudden, destructive hurricane forced the invaders to retreat back to Florida.[5] This same storm, which inadvertently saved Charleston from attack in 1686, also caused a tidal surge that damaged the capital’s earthen wharf. Waterfront erosion was likely an ongoing issue, but the damage from the 1686 hurricane was significant enough to prompt an appeal to the Lords Proprietors – the English investors who owned the entire colony.

Alt text: The 1711 Crisp Map of Charleston, highlighting the city walls and the developing waterfront along East Bay Street, indicating early urban planning and defense strategies.

During the winter of 1687, Governor James Colleton informed the Proprietors that Charleston’s earthen wharf (East Bay Street) was eroding into the river, threatening the foundations of waterfront houses. While the governor’s letter itself is lost, it likely detailed the core problem: no individual had a direct stake in the wharf’s property, as the tidal mudflat, like all colony lands, belonged to the Lords Proprietors. The provincial government could undertake repairs, but the young colony was too financially strained to tackle the issue alone. Continued damage to Charleston’s only wharf and adjacent buildings would discourage investment in South Carolina and impede its growth as a commercial port. To address this critical situation, some form of compromise or collaboration was needed.

Whatever persuasive language Governor Colleton used to request assistance from the Lords Proprietors, his plea was successful. In October 1687, the Proprietors responded with a brief but crucial statement: “We take notice that you write that ye wharfe at Charles Towne weares away and if not prevented will undermine the houses[.] We are willing [to concede that] the respective inhabitants should have liberty to wharfe in[,] each man before his owne house[,] and enjoy it to his owne use[,] provided that amongst them they wharfe in that part alsoe that is against the ends of the streets that open upon the river and keep it in constant repaire.”[6]

This seemingly concise property concession was the catalyst for transforming Charleston’s waterfront into the landscape we know today. To clarify its significance, we can rephrase the original text: The Lords Proprietors granted each owner of the nineteen town lots fronting the Charleston wharf the right to claim ownership of the tidal mudflat adjacent to their lot, east of the town wharf and down to the low water mark. This was contingent on their agreement, along with the provincial government, to assume two long-term responsibilities. First, each property owner west of the wharf was obligated to build and maintain a permanent revetment or seawall on the east side of the wharf, corresponding to their lot’s width. Second, the community as a whole, through the provincial government, would be responsible for constructing and maintaining similar revetments at the eastern ends of Broad, Tradd, and Queen Streets where they met the river.

The waterfront concession offered by the Lords Proprietors in October 1687 could have sparked a rapid advancement of private commercial activity in Charleston’s port. However, political infighting stalled progress for over six years. By the time the Proprietors’ letter reached Charleston in late 1687, South Carolina’s provincial government was mired in dysfunction. Political disagreements within the legislature led Governor James Colleton to dissolve parliament and later declare martial law. Seth Sothell, a Proprietor himself, seized the governorship in late 1690, ruling illegitimately for eighteen months. The arrival of Governor Philip Ludwell in spring 1692 brought stability, but persistent factionalism within the reorganized legislature hampered his authority. In short, political instability in South Carolina from 1687 to 1693 prevented the government from addressing the ongoing erosion of Charleston’s essential wharf.[7]

On the final day of a brief legislative session in May 1693, the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly briefly considered a bill for “wharfeing in ye banke at Charles Town.” After assigning the bill to Representative Robert Gibbes, the assembly adjourned for the summer without further action. Meanwhile, Governor Philip Ludwell left the politically charged colony, and Landgrave Thomas Smith officially became governor in autumn 1693.[8]

A few months later, in April 1694, the Lords Proprietors informed Governor Smith of their awareness “that ye ground weares away at Charles Towne for want of wharfing in.” The distant owners viewed the continued erosion of the capital’s primary waterfront as a “miscarriage” of their generous instructions from nearly seven years prior. Nevertheless, they reiterated their willingness to “gratifye ye persons concerned therein” to “save the street” that doubled as Charleston’s only wharf.

Accordingly, the Proprietors decreed “that every man that hath a lott on ye sea shall have liberty to wharfe in ye land before his lott in ye s[ai]d towne, and take a profit of it to himselfe[;] provided that ye persons who have ye benefit of this our concession doe settle some way amongst them, for the wharfing and keeping in constant repaire ye wharfes ag[ains]t ye ends of ye streets[;] also soe that there may be a [public] wharf for ye other inhabitants to land their goods at without charge.”[9]

Shortly after receiving this renewed directive from the Lords Proprietors, the South Carolina legislature began developing an immediate plan to preserve Charleston’s wharf. It’s unclear whether they revised the previous year’s bill or drafted a new one, but they acted swiftly. On June 20, 1694, the provincial assembly ratified “An Act to prevent the Sea’s further encroachment upon the Wharf at Charles Town.”[10]

Unfortunately, the complete text of this landmark law is lost. However, later government documents quote and summarize several key clauses. A committee report from the Commons House of Assembly in 1739 reveals that the “wharf act” of 1694 mandated the construction of a brick wall approximately 2,700 feet long, spanning the entire town wharf. Specifically, the wall was to extend “from the southernmost side of Capt. Bennet’s lot” (the southeast corner of town lot No. 1, now in front of 43 East Bay Street) “to the northwardmost side of Major Robt. Daniel’s lot” (the northeast corner of town lot No. 34, now in front of 215 East Bay Street). Each owner of the nineteen lots and subdivisions of lots west of this line (lot numbers 1–10, 13–17, 19, 32–34 in the Grand Model) was responsible for building a section of the brick wall on the wharf’s east side, corresponding to their property’s width.[11]

Original details regarding the height, width, and other specifications of the 1694 brick wall are now missing. The 1739 summary simply states that each property owner was “obliged to build a brick wall three feet thick.” Property owners who signed a bond after the act’s ratification (June 20, 1694), promising to complete their section of the wall within eighteen months, would be “entitled to a grant for the low water land lying before the wall so directed to be built.” Beyond securing these individual promises to begin construction, the 1694 law apparently did not set a construction schedule or coordinate the efforts of property owners.[12]

The “wharf act” of June 1694 appointed commissioners to oversee the project. However, no records indicate any completed work in 1694 or 1695, and no low-water lots were granted during this period. This doesn’t necessarily mean waterfront property owners neglected their responsibilities. A government review from spring 1696 shows that some property owners had submitted bonds, but none had completed their wall sections. In fact, there’s no evidence any construction had even begun.

Alt text: The 1739 Ichnography of Charles Town wharves, illustrating the developed waterfront of Charleston with multiple wharves extending into the Cooper River from East Bay Street.

This lack of progress could be attributed to various factors: a shortage of skilled bricklayers, insufficient brick supplies, lack of private funds, or simply reluctance to undertake such a demanding task. However, consider the project’s inherent challenges. Later revisions to the 1694 “wharf act” clarify that the brick wall was intended to have a substantial foundation, sunk deep into the pluff mud. To begin, each property owner would have needed to build a cofferdam to exclude tidal waters from their construction site. With a dam in place, they had to excavate a wide trench in the dense mud, lay a level wooden plank foundation, and then begin laying bricks and mortar. This was arduous, unpleasant, and expensive work. Yet, South Carolina’s government placed this major public works project squarely on private property owners. Their reward was the grant of free land extending from the improved town wharf into the Cooper River.

Twenty-one months after the 1694 “wharf act,” the South Carolina assembly passed a revised version, which survives in manuscript form. This document, along with over a dozen subsequent revisions and additions from 1696 to 1764, provides extensive details about the dimensions, materials, and location of Charleston’s first “wharf wall.” On March 16, 1696, the government ordered the wharf wall commissioners to “cause to be surveyed laid out and staked with sufficient ceader [sic] stakes the line upon which the wall mentioned in the said act is to be built.”[13]

Construction of Charleston’s first seawall definitely started after spring 1696, but further discussion of this project will be paused here. The story continues for another century, but it becomes intertwined with another narrative around the turn of the 18th century. Government discussions of the brick wharf wall after 1696 were framed within the broader context of urban fortifications, and by 1702, the seawall was considered part of an expanding system of defenses. This aspect of the story will be revisited in a future discussion about the construction of Charleston’s earliest permanent fortifications.

To conclude this exploration, let’s briefly summarize the civic and commercial history of Charleston’s first wharf, which evolved into East Bay Street. Beginning in spring 1698 and continuing for several years, South Carolina’s government granted low-water lots east of East Bay Street to the owners of the western lots. This confirms that sections of the wall were completed by the late 17th century, although full completion took more years. Starting after 1698, private individuals with titles to the tidal mudflat east of the town wharf began building wooden piers perpendicular to the original wharf. These “bridges,” as they were called in the early 18th century, extended eastward into deeper water, enabling larger vessels to dock and unload cargo directly onto wooden platforms.

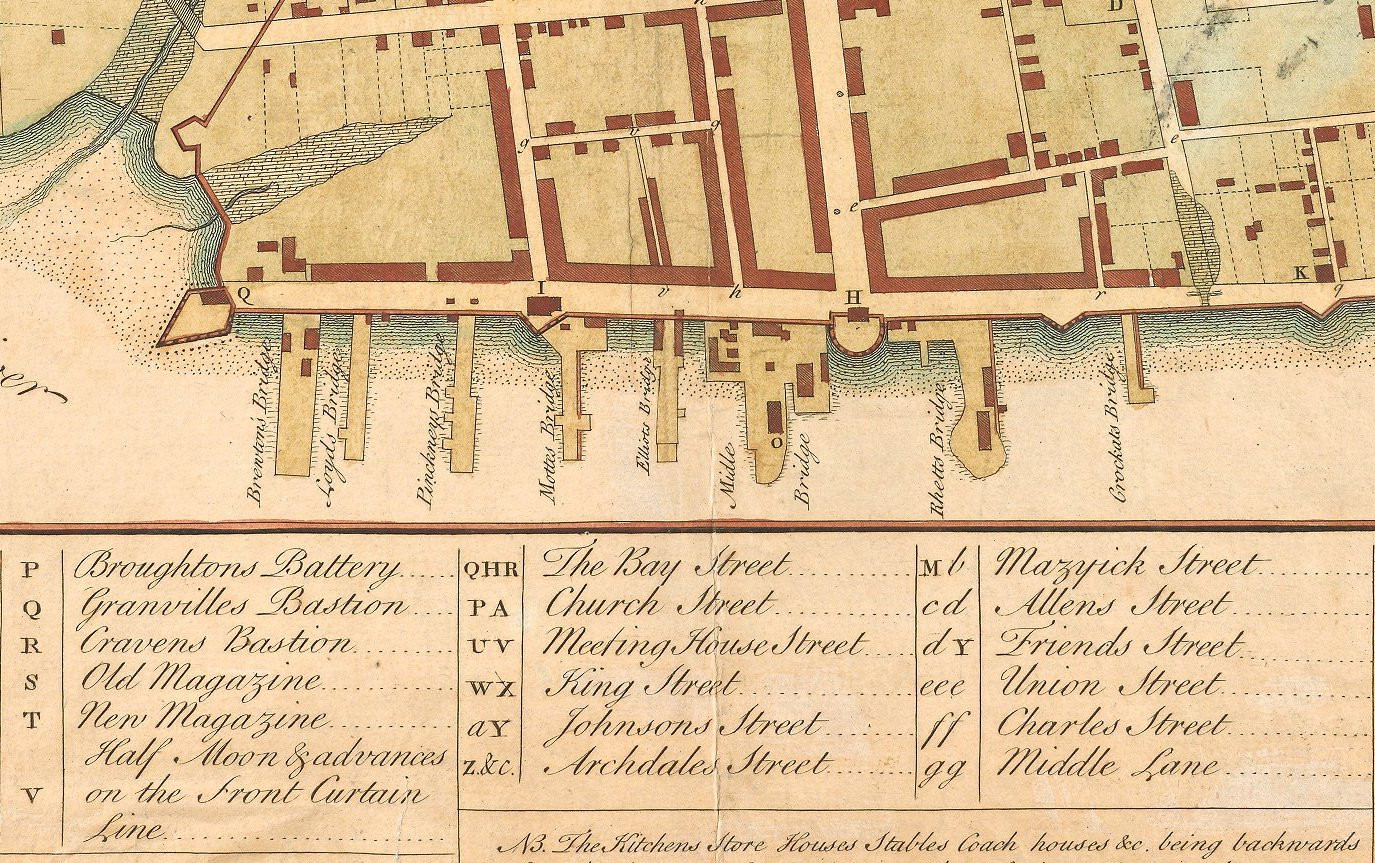

The construction of new wooden wharves perpendicular to the original town wharf progressed steadily throughout the 18th century. By 1711, when Edward Crisp of London published a map of Charleston, only two “bridges” projected into the Cooper River. By the early 1720s, there were four, and by 1739, Bishop Roberts’ “Ichnography of Charles Town” depicted eight wharves along the waterfront. At the start of the American Revolution in 1775, over a dozen expansive wooden wharves extended from East Bay Street, with only small sections of the original waterfront still visible. The upper sections of Charleston’s brick wharf wall were lowered to street level between 1785 and 1787, and permanent structures soon appeared on the street’s east side. Construction and land reclamation continued into the mid-20th century, creating the broad expanse of land we now see between East Bay Street and the Cooper River.

Finally, let’s touch upon the name of this historic street. As we know, it was initially described as a wharf in the 1680s. By 1696, if not earlier, Charlestonians began using a new name for their waterfront. A law from March 16 of that year referred to the town wharf as “the bay of Charles Towne.”[14] This term, “the Bay,” referring to the street, not the water, remained the standard designation for Charleston’s waterfront thoroughfare throughout the colonial era. “Bay Street” occasionally appears in records from the 1730s onward, but it wasn’t common until the late 18th century. “East Bay” and “East Bay Street” first appeared in local newspapers and documents after the American Revolution. By the 19th century, these became the standard names we still use today.

The next time you find yourself on East Bay Street, take a moment at the southeast corner of Tradd Street. There, you’ll find a display installed by the City of Charleston and the Mayor’s Walled City Task Force, illustrating the history of colonial-era fortifications at this site. This display reveals that you’re standing on part of Charleston’s original wharf wall, its foundations still buried beneath the modern streetscape on the east side of East Bay Street. This information acts as a virtual time machine, allowing you to see beyond the asphalt and concrete to the vast tidal mudflat that once defined Charleston’s original waterfront.

[1] For more information about the Grand Model, see Henry A. M. Smith, “Charleston: The Original Plan and the Earliest Settlers,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 9 (January 1908): 12–27.

[2] Samuel G. Stoney, ed., “A Contemporary view of Carolina in 1680,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 55 (July 1954): 154. The original source of this item is an undated manuscript “Coppie of a Letter from Charles Towne in Carolina,” located at Edinburgh University Library, Special Collections, Laing Collection, La. II, 718/1.

[3] For more information about the history of tidal inundation on the Charleston peninsula, see Christina Rae Butler, Lowcountry at High Tide: A History of Flooding, Drainage, and Reclamation in Charleston, South Carolina (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2020).

[4] The use of lighters to move ballast is mentioned, for example, in “An Act for the better regulating the Port and Harbour of Charles Town and the Shipping frequenting the same,” ratified on 9 April 1734. The text of this act was not included in the nineteenth-century published compilation of The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, but the engrossed manuscript survives at SCDAH. An “abstract” of the act appears in South Carolina Gazette, 6–13 July 1734. A “ballast master” continued in Charleston harbor at least to the 1770s.

[5] For an over view of the 1686 Spanish raid, see Lawrence S. Rowland, et al., The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina, Volume 1, 1514–1861 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996), 67–75. For a contemporary description, see J. G. Dunlop and Mabel L. Webber, eds., “Spanish Depredations, 1686,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 30 (April 1929): 81–89.

[6] Lords Proprietors to Governor James Colleton, 10 October 1687, in Colonial Entry Book Vol. 22, p. 121, published in A. S. Salley Jr., indexer, Records in the British Public Record Office Relating to South Carolina 1685–1690 (Atlanta: Foote and Davies for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1929), 227. Spelling original.

[7] For a description of the political situation in South Carolina between 1687 and 1693, see M. Eugene Sirmans, Colonial South Carolina: A Political History, 1663–1763 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966), 35–54.

[8] A. S. Salley, Jr., ed., Journals of the Commons House of Assembly of South Carolina for the Four Sessions of 1693 (Columbia, S.C.: The State Company for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1907), 25, 26.

[9] Lords Proprietors to their deputies at Charleston, 24 April 1694, in BPRO, Board of Trade, Carolina records, Vol. 4, pp. 13–14, published by A. S. Salley Jr., indexer, Records in the British Public Record Office Relating to South Carolina 1691–1697 (Atlanta: Foote and Davies for the Historical Commission of South Carolina, 1931), 119–23.

[10] Thomas Cooper, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 2 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1837), 81, assigned the number 110 to this act and identified its date as 16 June 1694, but subsequent revisions of this law, and later compilations of statute law published by Nicholas Trott in 1736 and John F. Grimke in 1790, as well as a report presented to the Commons House of Assembly in 1739, all cite the date as 20 June 1694.

[11] For a brief summary of the chain-of-title for these nineteen wharf-adjacent lots, which the provincial government granted to individuals between 1678 and 1695, see Susan Baldwin Bates and Cheves Leland, eds., Proprietary Records of South Carolina, Volume Three: Abstracts of the Records of the Surveyor General of the Province, Charles Towne 1678–1698 (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2007), 113–27.

[12] See the text of Act No. 131 in Episode No. 181, and the committee report debated by the Commons House on 15 March 1738/9, in J. H. Easterby, ed., Journal of the Commons House of Assembly November 10, 1736–June 7, 1739, 669–71.

[13] See the third section of Act No. 133, “An Act to Appropriate the Moneys Raised and to be Raised by an Imposition on Liquors, &c. Imported into, and Skinns and ffurrs Exported out of this Part of this Province to a ffortification in Charles Town,” ratified on 16 March 1695/6. Part of the text of this act is reproduced in David J. McCord, ed., The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, volume 7 (Columbia, S.C.: A. S. Johnston, 1840), 6–7, but the complete text is found at SCDAH, General Assembly, Acts, Bills, and Joint Resolutions, vol. 6: Book of Acts from 1696 (“Governor Archdale’s Lawes”), 84–87.

[14] The quoted phrase, extracted from the aforementioned Act No. 133, appears in McCord, Statutes at Large, 7: 6.

NEXT: Planning Charleston’s First “Fortress,” 1695–1696PREVIOUSLY: Charleston’s Contested Election of 1868See more from Charleston Time Machine