In the heart of Tulsa, Oklahoma, during the early 20th century, flourished a beacon of African American prosperity and self-determination known as the Greenwood District, or more famously, Black Wall Street. This thriving community stood as a testament to Black economic empowerment in a deeply segregated America. However, in 1921, this dream was brutally extinguished in one of the most devastating acts of racial violence in American history – the Tulsa Race Massacre.

The seeds of Greenwood were sown in 1906 when O.W. Gurley, a wealthy Black entrepreneur, purchased 40 acres of land in Tulsa with the explicit intention of creating a haven for African Americans. This vision attracted Black migrants fleeing the oppressive conditions of the Deep South, particularly Mississippi. Segregation, while a tool of oppression, inadvertently fostered a unique economic ecosystem within Greenwood. Denied services and opportunities in white Tulsa, Black residents channeled their resources and talents into their own community. This resulted in a remarkable concentration of Black-owned businesses and wealth.

“In 1906, O.W. Gurley, a wealthy African-American from Arkansas, moved to Tulsa and purchased over 40 acres of land that he made sure was only sold to other African-Americans,” writes Christina Montford in the Atlanta Black Star.

Greenwood was not just a collection of businesses; it was a vibrant, self-sufficient community. It boasted luxurious amenities unheard of in many parts of the country, for both Black and white communities. Josie Pickens in Ebony described it as “modern, majestic, sophisticated, and unapologetically black,” filled with “banks, hotels, cafés, clothiers, movie theaters, and contemporary homes.” Residents enjoyed luxuries like indoor plumbing and a superior school system that provided exceptional education to Black children. The economic strength of Greenwood was undeniable. Due to segregation, a dollar in Greenwood circulated within the community for as long as a year, multiplying its economic impact. Remarkably, at a time when Oklahoma had only two airports, six Black families in Greenwood owned their own airplanes, highlighting the extraordinary wealth accumulation within this district.

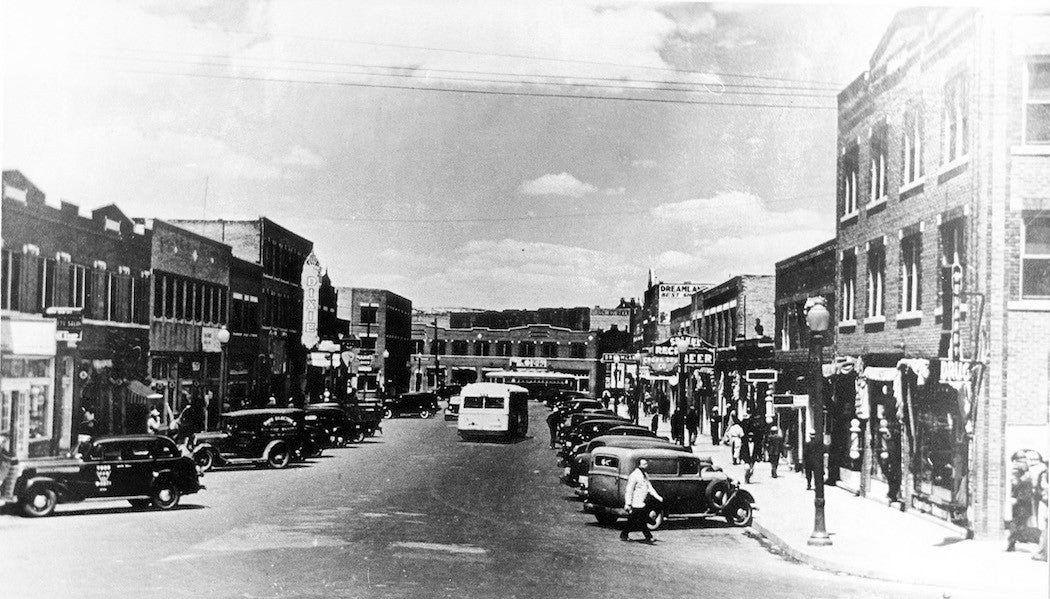

Historic photograph of Archer Avenue in Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma, also known as Black Wall Street, showcasing thriving businesses and streets before the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

Historic photograph of Archer Avenue in Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma, also known as Black Wall Street, showcasing thriving businesses and streets before the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

This prosperity, however, became a target. The racial animosity simmering beneath the surface of Tulsa society, fueled by white resentment of Black success and progress, was ignited by a spark of racial prejudice.

The Spark of Violence: The Tulsa Race Massacre

The Tulsa Race Massacre, a horrific episode of racial terror, erupted on May 31, 1921. The catalyst was a racially inflammatory report in the Tulsa Tribune. The newspaper alleged that a young Black man, Dick Rowland, had attempted to rape a white woman, Sarah Page, in an elevator. While accounts of the incident vary, the Tulsa Tribune’s sensationalized and racially charged reporting ignited immediate outrage among the white community.

Refusing to wait for any investigation or due process, white mobs descended upon the courthouse where Rowland was held. Confrontations with armed Black men, who arrived to protect Rowland from potential lynching, escalated into violence. Outnumbered, the Black men retreated to Greenwood. However, the white mob, fueled by racial hatred and a thirst for destruction, followed them, unleashing an orgy of violence upon Black Wall Street.

Eyewitness accounts and historical analysis reveal the systematic and brutal nature of the massacre. Homes and businesses were looted and set ablaze. Eyewitnesses reported that airplanes were used to drop incendiary devices, possibly kerosene or nitroglycerin, exacerbating the inferno that consumed 35 city blocks of Greenwood. Official accounts initially attempted to downplay the aerial involvement, claiming planes were merely conducting reconnaissance. However, the scale of destruction and eyewitness testimonies suggest a more sinister reality.

Greenwood survivors recount disturbing details about what really happened that night. Eyewitnesses claim “the area was bombed with kerosene and/or nitroglycerin,” causing the inferno to rage more aggressively.

The violence lasted for two days, leaving a trail of death and devastation. An estimated 300 people, mostly Black residents, were killed, and 800 more were injured. Nine thousand residents were left homeless, their lives and livelihoods reduced to ashes. The expressed motivation for this collective racial violence was the defense of white female virtue, a common trope used to justify racial terror against Black communities.

Unpacking the Underlying Causes of the Massacre

The Tulsa Race Massacre was not a spontaneous riot; it was the culmination of deep-seated structural and societal factors. Sociologist Chris M. Messer, in his study “The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921: Toward an Integrative Theory of Collective Violence,” delves into the underlying causes, highlighting several key elements.

The rapid growth of Tulsa, fueled by the oil boom and attracting both white and Black migrants, created a volatile racial dynamic. Tulsa became the city with the largest African American population in Oklahoma. This demographic shift, coupled with the economic success of Black Wall Street and the growing demands for racial equality, generated resentment and anxiety among the white population. For many whites, Black economic progress was perceived as a threat to the existing racial hierarchy and white dominance. The idea of Black citizens no longer accepting second-class status was deeply unsettling to the white establishment.

Segregation, ironically a foundation of Greenwood’s initial success, also played a paradoxical role in the massacre. While segregation fostered Black entrepreneurship by creating a captive market, it simultaneously limited Black opportunities and fueled white resentment. The visible economic success of Greenwood, achieved within the confines of a segregated system, became a source of envy and anger for some less prosperous white residents.

The role of law enforcement was also deeply complicit in the tragedy. The Tulsa police force failed to intervene effectively to prevent the violence. Instead, they actively exacerbated the situation by deputizing white men en masse and arming them, effectively sanctioning the mob violence. Black residents were arrested and interned in detention camps, while no white individuals were arrested during the riot itself, demonstrating a blatant disregard for due process and racial bias within the police force.

The media, particularly the Tulsa Tribune and the Tulsa World, played a significant role in inciting and justifying the violence. Sensationalized and racially charged reporting, coupled with the use of derogatory terms for Greenwood like “Little Africa” and “n—–town,” dehumanized the Black community and fueled white animosity. The media framed the violence as a Black uprising, falsely portraying Black residents as criminals and threats to social order. The Tulsa World even suggested the Ku Klux Klan could “restore order,” legitimizing white supremacist terror as a solution. This biased media narrative shaped public perception and justified the massacre in the eyes of many white Tulsans.

The Tulsa World newspaper inflamed the tensions between blacks and whites by suggesting that the Ku Klux Klan could “restore order in the community.”

The economic motivations behind the destruction of Black Wall Street cannot be ignored. Walter F. White of the NAACP, who visited Tulsa shortly after the massacre, concluded that Black economic prosperity was a key factor in the violence. Greenwood occupied prime real estate in Tulsa, ideal for industrial expansion. The destruction of Black Wall Street and the subsequent forced sale of Black-owned land at below-market prices benefited both private industries and the city government, paving the way for white-dominated economic development. The Reconstruction Committee established by the mayor just two days after the massacre aimed to redesign Greenwood for industrial purposes, revealing the opportunistic land grab that followed the violence.

The Lingering Scars and Forgotten Justice

Despite the immense economic and human cost of the Tulsa Race Massacre, justice and reparations for the victims and their descendants have been woefully inadequate. The Tulsa Race Riot Commission, established to investigate the massacre, recommended reparations for property losses and the creation of a scholarship fund. While a scholarship fund was briefly established, the broader recommendations for reparations and economic revitalization were never fully implemented.

Hannibal Johnson, author of Black Wall Street: From Riot to Renaissance in Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District, highlights the failure to provide meaningful reparations. The survivors and their families have largely been denied the financial and restorative justice they deserve. This lack of accountability and redress underscores the systemic racism that allowed the massacre to occur and its long-lasting consequences to persist.

While the Greenwood District was rebuilt by the 1940s, it never regained its former prominence. Integration during the Civil Rights era, while a victory for racial equality, also dispersed the concentrated economic power of Greenwood. The tragedy of Black Wall Street serves as a stark reminder of the fragility of Black economic progress in the face of systemic racism and white supremacy. It illustrates how easily economic envy, racial prejudice, and state-sanctioned violence can be mobilized to destroy Black wealth and communities.

The story of Black Wall Street and the Tulsa Race Massacre remains a vital, though often overlooked, chapter in American history. It is a story of Black resilience and achievement, brutally cut short by racial terror and economic greed. Understanding this history is crucial for confronting the enduring legacies of racial inequality and pursuing a more just and equitable future.

Promotional image for the JSTOR Daily article 'Seeking Clues in Cabinet Cards', featuring a man holding an antique camera, hinting at historical research and discovery.

Promotional image for the JSTOR Daily article 'Seeking Clues in Cabinet Cards', featuring a man holding an antique camera, hinting at historical research and discovery.

(Note: No explicit “More to Explore” section included as per instructions, but related link integrated within the text where appropriate.)