The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 stands as one of the most devastating acts of racial violence in American history, a horrific event that continues to cast a long shadow over Oklahoma and the nation. In a span of just eighteen hours on May 31 and June 1, 1921, the thriving Greenwood District of Tulsa, known as “Black Wall Street” for its affluence and Black-owned businesses, was systematically destroyed. This brutal assault resulted in the obliteration of over a thousand homes and businesses and caused deaths estimated to range from fifty to three hundred. In the aftermath, Tulsa was placed under martial law, thousands of Black residents were detained, and a vibrant community was reduced to ashes.

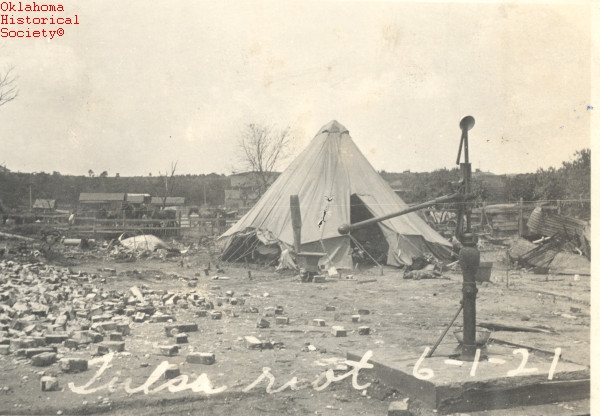

A photographer documents the widespread destruction in Greenwood, Tulsa, after the 1921 race massacre, highlighting the scale of devastation.

This tragedy was not an isolated incident but occurred within a broader context of intense racial tension across the United States. The resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and the courageous resistance of African Americans against racial terror, particularly lynchings, were national trends mirrored in Oklahoma and Tulsa.

By 1921, Tulsa had grown into a modern city with a population exceeding one hundred thousand. Within Tulsa, the Greenwood District was a remarkable testament to Black achievement. Home to approximately ten thousand African Americans, Greenwood was a self-sufficient community boasting two newspapers, numerous churches, a library branch, and a thriving hub of Black entrepreneurship, earning it the moniker “Black Wall Street.”

Displaced Black residents of Tulsa find temporary shelter in tents after the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre destroyed their homes in Greenwood.

However, beneath the surface of prosperity, Tulsa was also a city grappling with significant issues. High crime rates and vigilante violence were prevalent, underscored by the lynching of a white teenager accused of murder in August 1920. Reports at the time indicated a lack of intervention from Tulsa police to protect the lynching victim, who was forcibly removed from his jail cell.

Eight months later, a fateful encounter between Dick Rowland, a young Black shoeshiner, and Sarah Page, a white elevator operator, ignited the tinderbox of racial animosity and set the stage for the Tulsa Race Massacre. The precise details of what transpired in the Drexel Building on May 30, 1921, remain unclear. The prevailing account suggests that Rowland inadvertently stepped on Page’s foot in the elevator, causing her to scream.

The following day, the Tulsa Tribune, an afternoon newspaper, sensationalized the incident, reporting that Rowland had been arrested for allegedly attempting to rape Page. Eyewitness accounts further claim that the Tribune published a now-missing editorial titled “To Lynch Negro Tonight,” which fueled the already simmering racial tensions. By evening, calls for lynching Dick Rowland echoed through the streets of Tulsa.

Words quickly translated into action. By 7:30 p.m., a large crowd of white men had amassed outside the Tulsa County Courthouse, demanding that authorities hand over Dick Rowland. Sheriff Willard McCullough refused to yield to the mob’s demands. Around 9 p.m., as news of the escalating situation downtown reached Greenwood, a group of approximately twenty-five armed Black men, many of whom were veterans of World War I, traveled to the courthouse to offer their assistance in protecting Rowland. The sheriff declined their offer, and the men returned to Greenwood. Frustrated and enraged, members of the white mob then attempted to raid the National Guard armory but were deterred by a small contingent of guardsmen. Around 10 p.m., a false rumor spread in Greenwood that white rioters were attacking the courthouse. A larger group of Black men, numbering around seventy-five, returned to the courthouse to again offer their support to law enforcement. Once again, they were turned away. As they were departing, a white man attempted to disarm a Black veteran, and a shot rang out. The Tulsa Race Massacre had begun.

Black residents of Greenwood sift through the ruins of their homes and businesses after the Tulsa Race Massacre, desperately seeking salvageable possessions amidst the devastation.

Over the next six hours, Tulsa descended into chaos. White mobs, their initial goal of lynching thwarted, unleashed their fury upon the entire Black community. Intense clashes erupted along the Frisco railroad tracks, where armed Black residents bravely defended their community against the onslaught. In a chilling act of violence, an unarmed Black man was murdered inside a downtown movie theater. Carloads of armed white men terrorized Black residential areas with drive-by shootings. By midnight, fires had been deliberately set at the edges of the prosperous Black business district of Greenwood, the heart of Black Wall Street. In all-night cafes, white men openly organized for a full-scale invasion of Greenwood at dawn.

In the initial hours of the massacre, local authorities were conspicuously absent in their duty to quell the escalating violence. Disturbingly, Tulsa police officers deputized members of the white mob and, according to eyewitness testimony, instructed them to “get a gun and get a nigger.” Local National Guard units were mobilized, but they were primarily deployed to protect white neighborhoods from a phantom Black counterattack.

As dawn approached on June 1, thousands of armed white individuals converged on the borders of Greenwood. With daybreak, they surged into the district, systematically looting homes and businesses before setting them ablaze. Numerous acts of brutality were committed, including the murder of Dr. A.C. Jackson, a highly respected Black surgeon, who was shot after surrendering to a group of white attackers. Eyewitness accounts and some claims suggest that invading whites utilized a machine gun and possibly even airplanes in the assault.

The residents of Black Wall Street valiantly fought to protect their homes and businesses, with particularly fierce resistance centered around Standpipe Hill. However, they were ultimately overwhelmed by the sheer number and superior firepower of the white mob. By the time additional National Guard troops arrived in Tulsa around 9:15 a.m. on June 1, much of Greenwood, Black Wall Street, was already engulfed in flames.

The immediate aftermath of the massacre was marked by a brief period of martial law and a series of legal maneuvers that further compounded the injustice. Despite Dick Rowland’s exoneration, an all-white grand jury astonishingly placed the blame for the violence on the Black community. In a stark miscarriage of justice, no white individuals were ever convicted or imprisoned for the murders and arson committed during the Tulsa Race Massacre, the destruction of Black Wall Street.

The vast majority of Tulsa’s African American population was left homeless. Despite efforts by the white establishment to prevent the rebuilding of Greenwood and force the relocation of its Black residents, the resilient community began the arduous process of reconstruction within days. However, thousands were forced to endure the winter of 1921–22 living in tents, a stark reminder of the devastation they had suffered.

The deep wounds inflicted by the Tulsa Race Massacre persisted for generations. While Greenwood was eventually rebuilt, the prosperity of Black Wall Street was irrevocably lost, and many families never fully recovered. For decades, the massacre remained a taboo subject, particularly within Tulsa. In 1997, a state commission was established to investigate the historical atrocity. Its report recommended reparations for the remaining survivors. Subsequent investigations by scientists and historians have provided evidence supporting long-held beliefs about mass, unmarked graves containing the bodies of unidentified victims of the massacre.

The Tulsa Race Massacre remains a profound tragedy in Oklahoma history, a stark and potent symbol of the enduring struggle for racial justice and reconciliation in America. It serves as a critical reminder of the devastating consequences of racial hatred and the urgent need to confront the legacy of racial violence in the United States. The story of Black Wall Street and its destruction in the Tulsa Race Massacre is a vital part of American history that must be remembered and understood.

Scott Ellsworth

See Also

AFRICAN AMERICANS, CHARLES FRANKLIN BARRETT, GREENWOOD DISTRICT, KU KLUX KLAN, LYNCHING, NEWSPAPERS–AFRICAN AMERICAN, OKLAHOMA NATIONAL GUARD, JAMES BROOKS AYERS ROBERTSON, SEGREGATION, ANDREW J. SMITHERMAN, TULSA, TULSA TRIBUNE, TWENTIETH-CENTURY OKLAHOMA

Browse By Topic

Explore

Learn More

version=”1.0″?Scott Ellsworth, Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1982).

John Hope Franklin and Scott Ellsworth, eds., The Tulsa Race Riot: A Scientific, Historical and Legal Analysis (Oklahoma City: Tulsa Race Riot Commission, 2000).

Eddie Faye Gates, They Came Searching: How Blacks Sought the Promised Land in Tulsa (Austin, Tex.: Eakin Press, 1997).

Loren L. Gill, “The Tulsa Race Riot” (M.A. thesis, University of Tulsa, 1946).

Robert N. Hower, “Angels of Mercy”: The American Red Cross and the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot (Tulsa, Okla.: Homestead Press, 1993).

Mary E. Jones Parrish, Events of the Tulsa Disaster (Tulsa, Okla.: Out on a Limb Publishing, 1998).

Related Resources

100 Block North Greenwood Avenue, National Register of Historic Places

Vernon A.M.E. Church, National Register of Historic Places

Tulsa Race Riot Report (PDF), Oklahoma Historical Society

Interview with Otis Clark, Voices of Oklahoma

Interview with Wess and Cathryn Young, Voices of Oklahoma

Citation

The following (as per The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition) is the preferred citation for articles:Scott Ellsworth, “Tulsa Race Massacre,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=TU013.

Published January 15, 2010 version=”1.0″? Last updated July 29, 2024

© Oklahoma Historical Society

Submit a Correction Terms of Use About the Encyclopedia

Copyright and Terms of UseNo part of this site may be construed as in the public domain.

Copyright to all articles and other content in the online and print versions of The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History is held by the Oklahoma Historical Society (OHS). This includes individual articles (copyright to OHS by author assignment) and corporately (as a complete body of work), including web design, graphics, searching functions, and listing/browsing methods. Copyright to all of these materials is protected under United States and International law.

Users agree not to download, copy, modify, sell, lease, rent, reprint, or otherwise distribute these materials, or to link to these materials on another web site, without authorization of the Oklahoma Historical Society. Individual users must determine if their use of the Materials falls under United States copyright law’s “Fair Use” guidelines and does not infringe on the proprietary rights of the Oklahoma Historical Society as the legal copyright holder of The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and part or in whole.