Hayes Street Grill stands as a San Francisco culinary landmark, a testament to enduring quality and a passion for fresh, uncomplicated seafood. Founded in 1979 by Patty Unterman, this Hayes Valley restaurant has remained remarkably consistent, a comforting anomaly in a city of ever-changing dining trends. From its hand-written tickets to its decades-long staff, Hayes Street Grill offers a glimpse into a different era of San Francisco dining, one built on personal connection and unwavering dedication to its craft. Spending a morning with Patty Unterman reveals the energetic heart of this institution and the principles that have allowed Hayes Street Grill to thrive for over four decades.

patty unterman hayes street grill

patty unterman hayes street grill

Untermans’s day begins before most restaurants even consider opening, immersed in the daily ritual of menu creation. A whirlwind of activity, she darts between the kitchen and basement office, a flurry of notes and decisions shaping the day’s offerings. This isn’t a passive process; Unterman actively engages with the ingredients, tasting grapefruit to assess its salad-worthiness, checking the texture of satsuma sorbet batches. This hands-on approach, this relentless pursuit of quality, is the engine that drives Hayes Street Grill. Observing this energetic process, one quickly understands a core truth about Patty Unterman: she is a force of nature, someone who doesn’t wait for opportunities, but creates them.

This proactive spirit is evident throughout Unterman’s career. At just 25, she launched her first restaurant without formal culinary or business training. Her second venture, Hayes Street Grill, opened the same year she became the San Francisco Chronicle’s first food critic, a role she essentially invented. For fifteen years at the Chronicle, and later for twenty at The Examiner, she championed local, unpretentious eateries, influencing San Francisco’s culinary landscape profoundly. Her co-founding of the Ferry Plaza Farmers Market further cemented her impact, revolutionizing how San Francisco restaurants sourced ingredients. To understand San Francisco food culture is to understand Patty Unterman’s indelible mark upon it.

The question arises: what sustains Hayes Street Grill after nearly forty years? While adaptation is often cited as the key to longevity, Hayes Street Grill appears remarkably unchanged since its inception in 1979. Handwritten tickets remain the norm, accounting is analog, and the most modern piece of technology seems to be a vintage Apple computer, its age a playful mystery to Unterman. This commitment to tradition extends beyond the systems and into the very heart of the restaurant: its staff.

In a city grappling with restaurant staffing challenges, Hayes Street Grill boasts an extraordinary level of staff retention. This is a notable anomaly, a testament to the unique environment Unterman has cultivated. The bedrock of the kitchen is Mama Lin, who has been with the restaurant since day one. Living above the Grill, Lin’s arrival was serendipitous, a neighbor expressing a desire to work. Despite language barriers and unknown culinary experience, Unterman recognized Lin’s inherent capability. Now in her eighties, Mama Lin remains the quiet force that binds the kitchen together.

Unterman describes Mama Lin as the one who “fills in all the cracks,” mastering crucial dishes like crab cakes, soups, and tomato sauce, handling mise en place, and executing countless unseen tasks essential to the menu’s success. Lin’s true genius, however, lies in her instinctive culinary understanding. “Lin can taste something once, smell it, and know how to make it. It’s remarkable,” Unterman emphasizes, highlighting the irreplaceable nature of Lin’s contribution.

hayes street grill gourmet magazine

hayes street grill gourmet magazine

Crab cakes were indeed a priority that morning, showcasing Mama Lin’s expertise. Executive chef Adriano Yerena is another long-term fixture, his connection to Unterman beginning in his youth, selling berries from his family’s Yerena Farms at the Ferry Plaza Farmers Market. Years later, after culinary school, Unterman welcomed him as an intern, and he has been a dedicated presence ever since. While Yerena is moving on to focus on his family farm, his loyalty to Unterman and Hayes Street Grill is clear: “Patty is my mentor. Of course I’m always going to be here if she needs me,” he affirms.

John Bissell, another veteran, has been with Hayes Street Grill since its very beginning, experiencing nearly every front-of-house role. Starting as a busboy, Bissell’s long tenure stems from a genuine belief in the restaurant’s food. “There was this huge hands-on quality to it, and here I am. It’s been 38 years,” he reflects, highlighting the enduring appeal of the restaurant’s ethos.

Unterman attributes this remarkable staff loyalty to a sense of intimacy forged over years of shared experiences, of navigating countless lunch and dinner rushes together, of becoming deeply intertwined in each other’s lives. It’s a family dynamic, where loyalty runs deep. Adriano Yerena sums it up succinctly: “Sometimes we hate each other, but we always have each other’s backs.” For Unterman, it boils down to genuine care for her employees. “I feel very dedicated to my workers. I try to be fair and help everyone. The people we employ have houses. We’ve been lucky that we’ve been able to pay people well for so long that they can have a life here,” she explains, acknowledging the importance of fair wages and a supportive work environment in fostering long-term commitment. Hayes Street Grill hired staff in an era when restaurant work could provide a stable, comfortable life in San Francisco, fostering a loyalty rarely seen in today’s transient restaurant landscape.

Hayes Street Grill’s opening coincided with a very different Hayes Valley, a neighborhood Unterman describes as a “war zone.” Divided by a now-removed highway overpass, the area west of Hayes Street was marginally acceptable, while the other side faced significant challenges, including open heroin dealing and frequent gunfire. Despite the neighborhood’s rough edges, Unterman recognized an opportunity. Davies Symphony Hall was under construction, and she knew there would be an audience seeking pre-performance dining options. Drawing on her experience from Beggar’s Banquet, her first, humble Berkeley restaurant, she took the leap.

Patty Unterman’s background is far from the typical restaurateur profile. She opened both Beggar’s Banquet and Hayes Street Grill with no formal culinary training, her education rooted in journalism. Her culinary journey began with classes from French cook Josephine Arnaldo and a deep dive into Julia Child’s cookbooks. With her college roommate, who Unterman jokingly describes as someone who “didn’t know how to fry an egg but was willing to jump right in,” she took over a tiny, eight-table space in Berkeley for Beggar’s Banquet. The minuscule kitchen, equipped with basic home appliances, was “like cooking at home except that there were eight tables,” Unterman recalls.

Despite its humble beginnings, Beggar’s Banquet thrived, attracting students with a daily chalkboard menu of three dishes. The star attraction? Mousseline of sole, a classic Julia Child recipe: fish ground with egg whites, nutmeg, and seasonings, sautéed and topped with duxelles and beurre blanc. In today’s challenging restaurant climate, Unterman’s seemingly effortless entry into the industry feels almost audacious. Yet, she operated with a refreshing disregard for conventional paths. “I had Julia Child, I had the books, I’d eaten, and I knew what I wanted,” she states simply.

This straightforward resolve, this unwavering belief in her vision, is a defining characteristic of Patty Unterman. Doubt seems to dissipate in the face of her passion for good food. Her ventures are driven by a desire to share culinary pleasure, a motivation too powerful to be derailed by uncertainty. Of course, opening a restaurant in 1979 was a different landscape than 2017. Back then, passion, cookbooks, willing friends, and a bit of capital were often enough.

Unterman’s love of food is deeply ingrained, nurtured by a discerning family and ignited by an awakening culinary journey through France, Italy, and Spain. “I couldn’t believe how great the food was,” she recalls of her European travels. Her grandmother instilled local food values, fostering a childhood filled with the flavors of fresh peaches, berries, and tomatoes from their Michigan City summer home. “Once you grow up tasting that, it’s hard to go back,” she explains, emphasizing the lasting impact of early exposure to quality ingredients.

This enduring love for food remains her driving force. When asked about her current home cooking, Unterman’s enthusiasm is palpable. “Soups!” she exclaims. “Delicious soups.” She delves into the details of her kitchen, describing the hours-long simmering of turkey carcasses for stock, the precise chopping of vegetables, and the transformative power of simmering parmesan rinds in broth for at least two hours. This same simple sensibility, this focus on fundamental techniques and quality ingredients, underpins the menu at Hayes Street Grill.

Grilled shrimp with greens and crema, seared scallops, flank steak, Dungeness crab with avocado – the menu is intentionally unfussy. Hayes Street Grill doesn’t strive for culinary revolution; instead, it offers hearty, reliable, and comforting food. This philosophy is rooted in the Berkeley food scene of the 1970s, the era of Chez Panisse and a burgeoning appreciation for simple, locally-sourced cuisine. Hayes Street Grill embodies those ideals of sharing and genuine hospitality, prioritizing consistent quality over fleeting trends. Co-owner Dick Sander echoes this sentiment: “If I never eat another 15-course tasting menu in my life, I’ll be fine. I would choose a good roast chicken any day,” reflecting a preference for rustic, familiar flavors over elaborate presentations.

Unterman’s other great passion, travel, is intrinsically linked to her love of food. The concept for Hayes Street Grill emerged while she and Sander were on a Yugoslavian beach, savoring grilled shrimp along the Adriatic coast. “It was such a beautiful way to eat. The open fire, the fresh fish, fresh herbs, fresh vegetables. I said, we’re gonna do something like that. This is what I want to eat,” she recounts.

Returning home, she began planning. She partnered with three friends from Beggar’s Banquet: Robert Flaherty, a lawyer seeking refuge in restaurant work; Anne Powning, a friend with French culinary influences; and Dick Sander, her current partner. Sander, initially not a “food person,” was captivated by the Berkeley food scene’s focus on good wine, exceptional produce, and artful cooking. “Never in a million years did I think I’d be a food person,” he admits, “but forty years later and it’s given me a good life.”

hayes street grill staff

hayes street grill staff

From the outset, Unterman established core principles for Hayes Street Grill: fresh, sustainable, high-quality fish, without compromise. She envisioned a menu that was quick to prepare, avoiding pre-made components, ideal for pre-theater diners. Drawing inspiration from classic grills, she committed to sourcing superior, responsibly caught seafood. When Davies Symphony Hall opened, Hayes Street Grill was perfectly positioned to cater to concertgoers, offering a welcome dining option in a developing neighborhood.

Hayes Valley has since transformed into a vibrant culinary destination, yet Hayes Street Grill remains a popular draw. The restaurant’s walls, adorned with signed photos of performers from decades past, narrate its history. The décor, with its deep green carpet and floral banquettes, evokes a sense of timelessness. Even on a Tuesday morning, a limousine arrival signals the start of the pre-matinee crowd, and within half an hour, the restaurant is bustling.

Unterman believes the key to success is identifying and fulfilling a need, serving underserved communities. However, owning Hayes Street Grill is also deeply personal, fulfilling her own desires. “Truthfully it fills a need for me, and I couldn’t do anything that didn’t fill a need for me,” she explains. Her transition to restaurant critic allowed her to share her culinary passions and guide others towards delicious experiences, mirroring her restaurant ownership goals. When she began her role at the Chronicle, food criticism was a nascent field. She modeled her approach on Caroline Bates of Gourmet magazine, admiring Bates’ fairness and her ability to educate readers about food with both love and insight. “I want to turn people onto stuff that I love,” Unterman decided.

Her focus was often on “ethnic food,” exploring small Vietnamese, Thai, and Chinese restaurants, conducting research, and traveling abroad to experience cuisines firsthand. “I always thought that was important, and luckily, the Chron went along with it,” she notes. This stands in stark contrast to the current state of food criticism, particularly the shrinking budgets and diminished travel opportunities for journalists. When asked about contemporary criticism, Unterman offers a gentle perspective. “I think it’s about to change. I mean, how long can you go? I don’t know. The whole thing has changed. The Internet has practically supplanted everything, to tell you the truth. We have easy access to every magazine, Eater—which I love—and all these great writers.”

However, her core beliefs about the role of a critic remain unchanged: integrity, understanding, and experience are paramount. “The mission of a critic is to have a really deep, intelligent understanding of food and how food is cooked. That includes study, hands-on experience, and whatnot. And then, that person has to be relatively unprejudiced. I really think the most important thing is the food itself,” she asserts. While acknowledging the importance of service and ambiance, Unterman emphasizes that ultimately, taste reigns supreme.

Addressing potential conflicts of interest arising from owning a restaurant while reviewing others, Unterman maintains she always strived for fairness, pointing to the New York Times’ practice of hiring novelists to review novels as a parallel. Her reviews generally focused on smaller, lesser-known establishments, not direct competitors, aiming to highlight deserving places. “I think a good critic should make people hungry for the good stuff. To be able to write in a way that shows the joy of eating something really tasty. I think that’s so important, because that’s the most fun,” she believes.

For Patty Unterman, both food and writing are vehicles for sharing pleasure, for making deliciousness accessible. Her love of food manifests in eating, cooking, writing, and engaging with it through all senses. A key aspect of her approach is generously sharing this love with others. This naturally leads to a conversation about sexism in the restaurant industry. Having worked in the food world for over four decades, Unterman’s experience offers a unique perspective. “I’ve always been the boss,” she states, implying that her position shielded her from much of the misogyny prevalent in kitchens.

While acknowledging the complexities of harassment, particularly in light of the Mario Batali case, Unterman’s generation of food professionals emerged from a different cultural context, one influenced by the free love movement and less rigid workplace norms. She and Sander recall a more “open” era in restaurant culture, with chefs included. “There was a lot of drinking, a lot of drugs, a lot of staying out late in the kitchen. And when you’re partying with everyone like that you do get very close. In the beginning days of this restaurant we all went out every night. Stars was going, and such an exciting time,” Sander recounts.

This era, while romanticized in retrospect, also presents a complex picture of blurred boundaries and potential for exploitation. The shared sensuality of food, wine, and late-night kitchen camaraderie could, in some instances, obscure or excuse problematic behavior. However, the critical element of power dynamics must be considered in these conversations. Despite these complexities, what emerges most strongly about Patty Unterman is her inherent generosity and warmth. Her radiant smile and joyful spirit are constants, reflecting a life deeply intertwined with the sensual pleasures of food and the act of sharing them. Cooking, for Patty Unterman, is simply an act of love.

As Unterman prepares to depart for Mexico, a delivery of game birds arrives – a snow goose and two mallards. While snow geese are less desirable for eating, the kitchen will experiment with preparations. Showing the mallards, Unterman tenderly holds their heads together, noting, “They mate for life, you know. I’ll bet these were a pair,” stroking their heads with reverence. Regardless of what the future holds for Hayes Street Grill, Patty Unterman’s enduring presence ensures that love will remain a central ingredient.

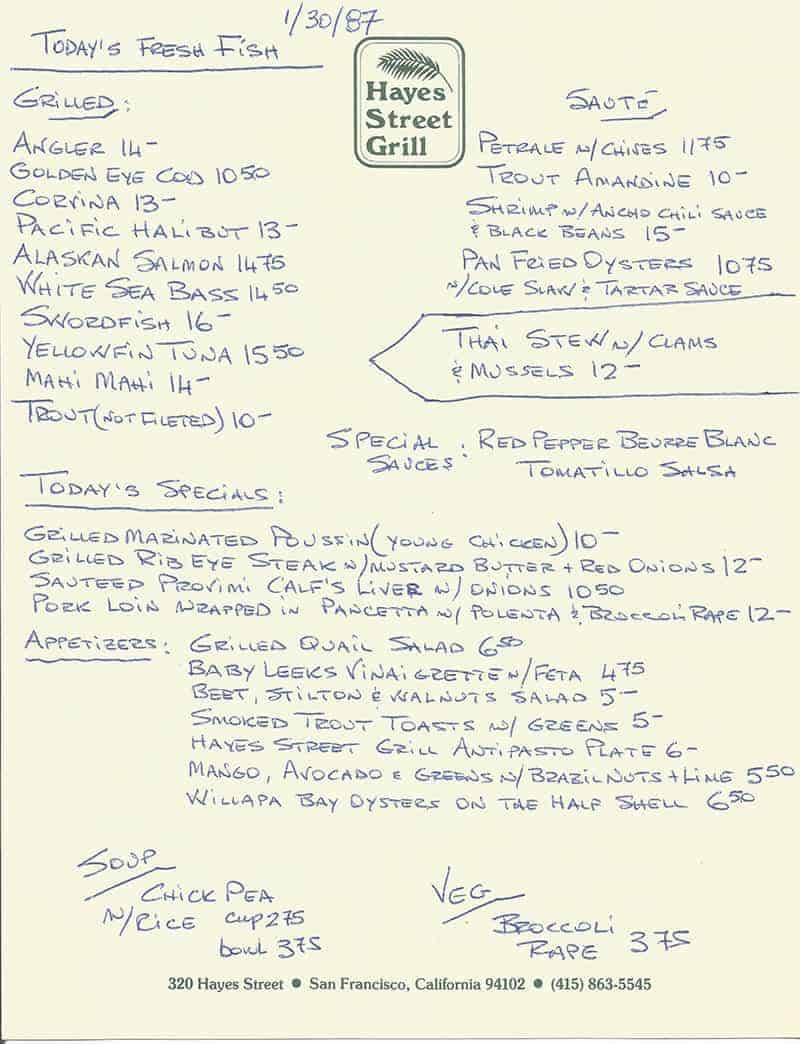

hayes street grill menu 1987

hayes street grill menu 1987