La Salle Street Train Station in Chicago was more than just a transportation hub; it was a landmark that witnessed significant moments in railroad history and even made its mark in Hollywood. Officially known as La Salle Street Station, but also historically recognized as Rock Island Station, this grand terminal stood at the corner of South La Salle and West Van Buren streets from 1903 until its demolition in 1981. Designed by the architecture firm Frost & Granger, the station served as a vital gateway for major railroad lines and iconic trains, leaving an indelible mark on Chicago’s urban landscape and transportation narrative.

The story of La Salle Street Station begins in the early 20th century, replacing the previous Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Depot II. As reported by the Inter Ocean newspaper on June 12, 1901, plans for a new, modern passenger station were underway. Architects Frost & Granger were commissioned by the Rock Island, Lake Shore, and Nickel Plate railroads to design a structure that would not only be functional but also a statement of architectural innovation. The article highlighted the intention to construct a “plain” exterior but with a “handsomely decorated” interior, equipped with every “modern convenience.” A temporary station was planned to be built one block south on Harrison Street to maintain railway operations during construction.

Plans for a new passenger station for Rock Island, Lake Shore, and Nickel Plate railroads, as announced in the Inter Ocean newspaper in 1901.

Plans for a new passenger station for Rock Island, Lake Shore, and Nickel Plate railroads, as announced in the Inter Ocean newspaper in 1901.

The Inter Ocean article detailed the ambitious scale of the project. The main building was planned to front Van Buren Street, extending southward, connected to a concourse and a vast train shed stretching to Harrison Street. Elevated tracks, accommodating eleven lines, were a key feature. Below the elevated tracks, the design included cab stands, baggage and express delivery areas, all integrated with elevators and potentially mail chutes for efficient operations. The train shed was to be constructed of steel, concrete, and asphalt, while the main building promised a blend of granite and vitrified brick. Inside, a grand lobby, ticket offices, waiting rooms, and dining facilities were designed for passenger convenience. The upper floors were designated as office space for the railroad companies.

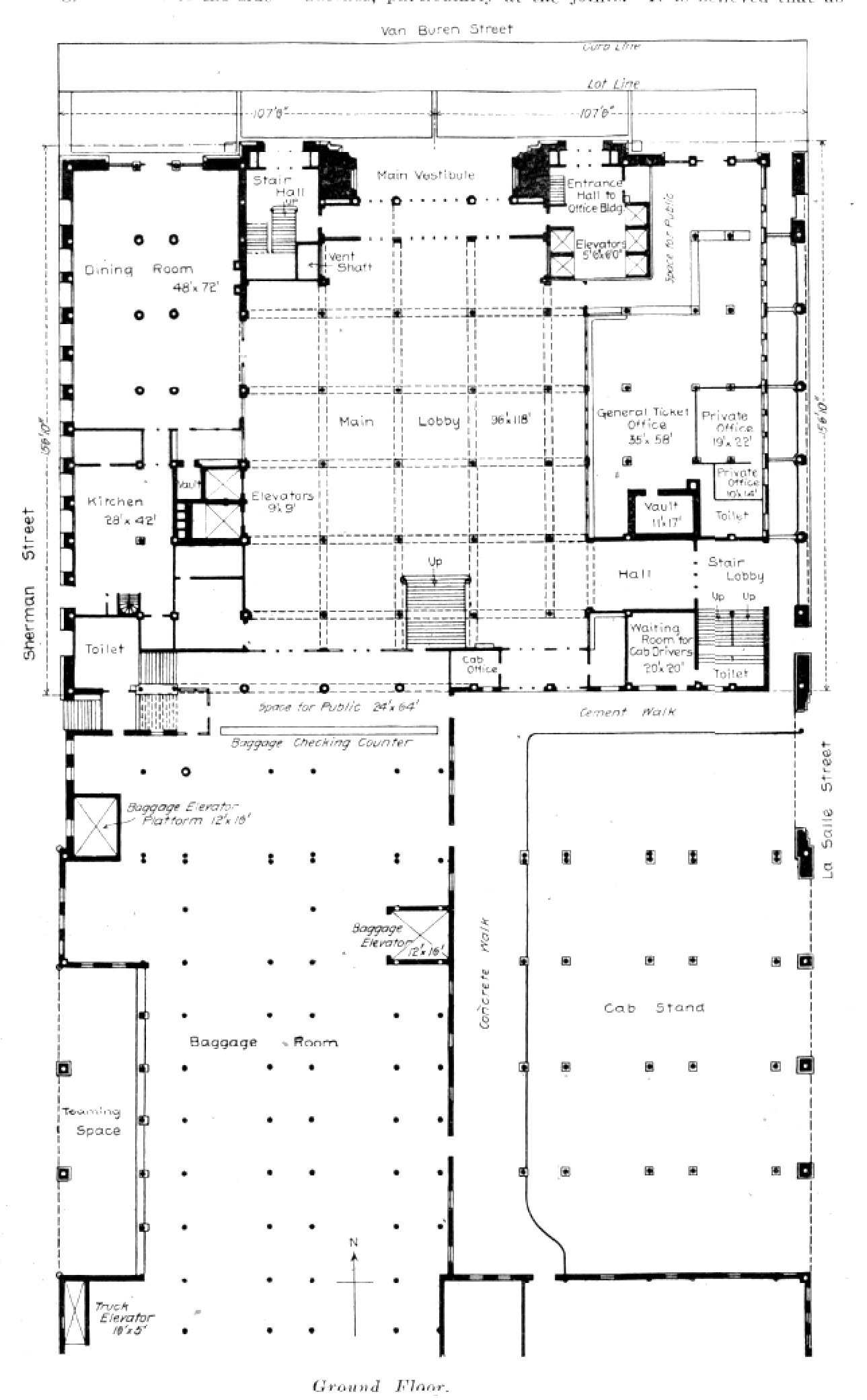

Further details emerged in The Railroad Gazette on March 14, 1902, announcing the commencement of construction by Grace & Hyde Co. The article emphasized the scale of the building, noting its 215-foot frontage on Van Buren Street and a height of 10 stories. Granite and red paving brick were specified for the exterior, and a steel grillage foundation on 50-foot pilings demonstrated the advanced engineering for the time. The plans reiterated the track elevation and provided insights into the layout of the first and second floors.

Floor plan of the first (ground) floor of the new Van Buren Street Passenger Station in Chicago.

Floor plan of the first (ground) floor of the new Van Buren Street Passenger Station in Chicago.

The ground floor, as described, featured a central lobby, a dining room, and a general ticket office. Space under the elevated tracks was allocated for baggage, express, and a cab stand, even including a waiting room for cab drivers, showcasing attention to detail and operational efficiency. The second floor, at track level, housed the main waiting room, a women’s waiting room, smoking room, and other passenger amenities. A concourse connected the waiting area to the tracks. Notably, a direct stairway to a street entrance and a passageway to the Union Elevated Loop station were designed to enhance passenger flow. Interior finishes were planned to be luxurious, with marble, mahogany, and oak envisioned for different areas of the station.

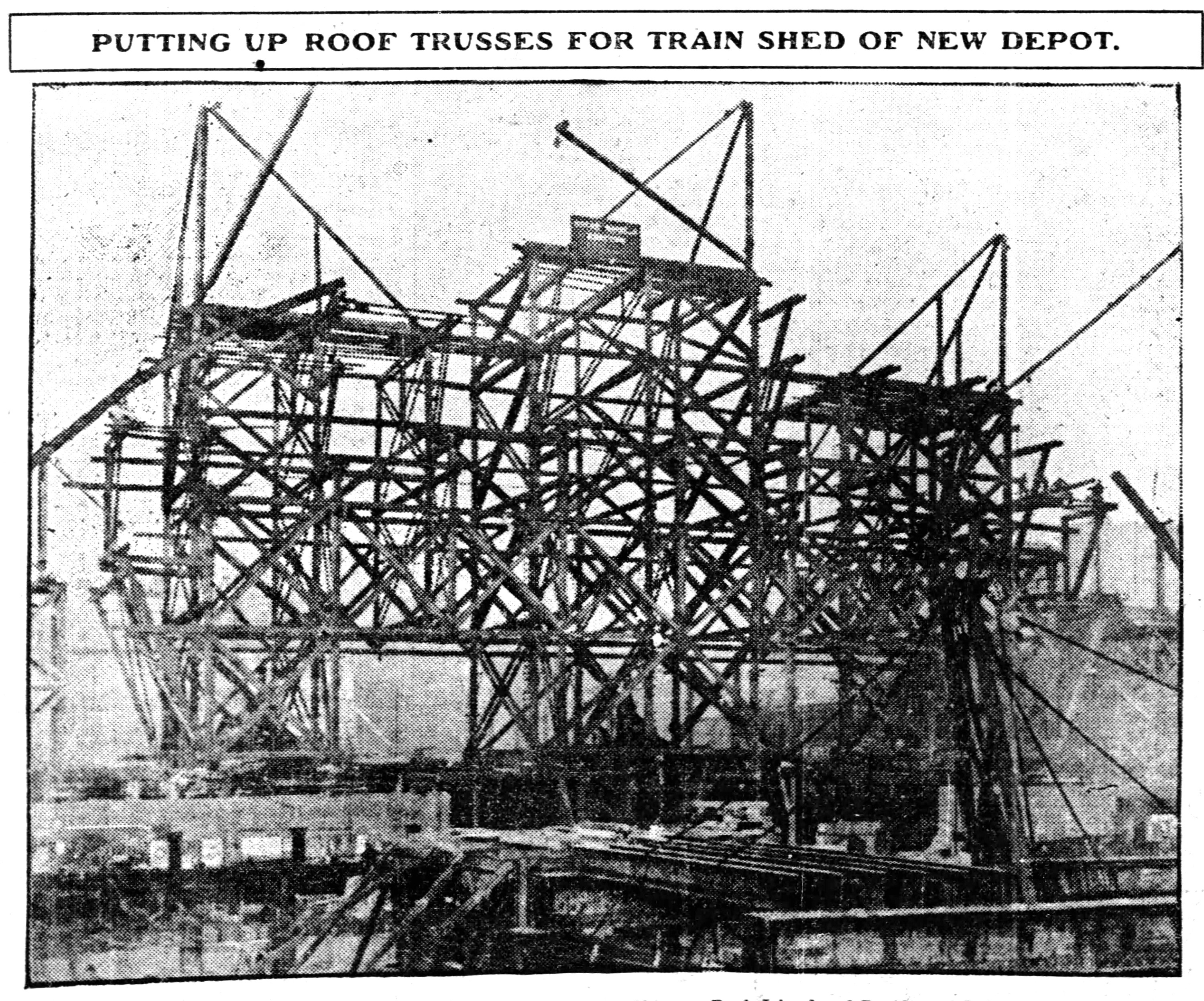

Construction progressed rapidly. A Chicago Tribune article from November 8, 1902, reported on the installation of the massive roof trusses for the train shed. Each 208-foot span truss was being carefully positioned, with expectations to have the shed roofed by Christmas and the entire building near completion by July 1, 1903. The anticipation was high for the station to bring passengers closer to Chicago’s business center.

Construction of the roof trusses for the new train shed at La Salle Street Station in 1902.

Construction of the roof trusses for the new train shed at La Salle Street Station in 1902.

Finally, on July 11, 1903, the Chicago Tribune announced the grand opening of the new La Salle Street Station. Starting that day, trains from the Lake Shore, Rock Island, and Nickel Plate railroads would operate from the new depot. The article detailed the station’s division into a 13-story office building and the expansive train shed. The shed, spanning 213×575 feet, was illuminated by prismatic glass walls and skylights, creating a bright interior. The ground floor lobby, waiting rooms adorned with marble and mahogany, and connections to the Union Elevated Loop were highlighted as key features designed for passenger convenience and efficient traffic flow.

Headline from the Chicago Tribune announcing the opening of La Salle Street Station on July 11, 1903.

Headline from the Chicago Tribune announcing the opening of La Salle Street Station on July 11, 1903.

La Salle Street Station quickly became a prominent terminal, serving as the Chicago terminus for prestigious trains. Among the most celebrated were the New York Central’s 20th Century Limited, operating from 1902 to 1967, and the Rock Island-Southern Pacific Golden State Limited, running from 1902 to 1968. These name trains epitomized luxury rail travel and connected Chicago to major destinations across the country.

Advertisement announcing the opening of La Salle Street Station in the Chicago Tribune on July 11, 1903.

Advertisement announcing the opening of La Salle Street Station in the Chicago Tribune on July 11, 1903.

The station’s grandeur also attracted Hollywood. Alfred Hitchcock’s 1959 thriller North by Northwest, starring Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint, featured scenes filmed at La Salle Street Station, showcasing its iconic waiting room and concourse to a global audience. Later, in 1973, the station served as a backdrop in the classic movie The Sting, starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford, further cementing its place in popular culture.

La Salle Street Station featured in the movie North By Northwest in 1959.

La Salle Street Station featured in the movie North By Northwest in 1959.

La Salle Street Station waiting room around 1910, showcasing its grand interior.

La Salle Street Station waiting room around 1910, showcasing its grand interior.

Despite its historical significance and architectural beauty, La Salle Street Station faced the changing tides of transportation. By the late 20th century, rail travel declined, and the station’s usage diminished. The Chicago Tribune reported on December 23, 1980, about the plans for the station’s demolition and replacement with a 25-story office tower. An interim station was planned to serve commuters during the construction period. The demolition of La Salle Street Station in 1981 marked the end of an era.

Headline from the Chicago Tribune on December 23, 1980, announcing plans for the demolition of La Salle Street Station.

Headline from the Chicago Tribune on December 23, 1980, announcing plans for the demolition of La Salle Street Station.

Today, while the original La Salle Street Train Station is no longer standing, its legacy persists in Chicago’s memory. The station’s history is a testament to the golden age of rail travel and the architectural ambition of early 20th-century Chicago. Although replaced by a modern office building with a smaller commuter rail facility, the stories and images of the grand La Salle Street Station continue to evoke a sense of nostalgia for a bygone era of elegant train travel and Chicago’s rich transportation heritage.