For those in the know, mentioning Norfolk Street evokes a certain curiosity, especially among New York University students and city dwellers alike. The common reaction? “Norfolk Street? Where exactly is that?” often paired with a hint of surprise, even slight disappointment, at discovering a corner of the city yet unexplored.

This unfamiliarity is precisely Norfolk Street’s charm. It’s one of those urban pockets that subtly resists the spotlight, a place that seems to intentionally fly under the radar.

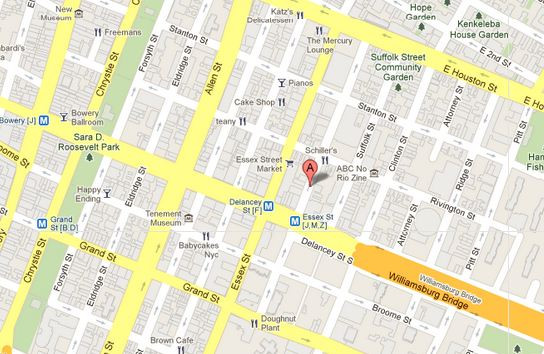

Nestled in the Lower East Side (LES), Norfolk Street runs directly south from East Houston Street, a mere stone’s throw from the Williamsburg Bridge’s Delancey Street entrance. It continues its quiet journey southward until it meets Grand Street.

Norfolk Street isn’t a bustling destination, nor is it a place you’d casually stroll from end to end. Yet, for those who take the time, like myself, who have walked its length countless times, an undeniable, almost peculiar feeling emerges. Stepping onto Norfolk Street and remaining there feels different. It’s as if the street primarily functions as a connector, a quiet artery between its more animated neighbors like Rivington and Stanton Streets. You get the distinct sense of pausing in a space designed for passage, a street people traverse to reach somewhere else.

This transient essence was captured by photographer Dylan Stone in his evocative project, “Drugstore Photographs, or A Trip Along the Yangtze River, 1999.” Stone’s extensive collection of Lower East Side snapshots, meticulously detailed and inclusive, encompasses 26,000 photographs of LES street corners and buildings. This remarkable archive is accessible online through the New York Public Library’s digital collections. Stone’s work intentionally blurs the lines between documentation and art, presenting the street as it is while simultaneously striving to convey its unique feel. His Norfolk Street photographs are characterized by a muted palette and an almost deliberate awkwardness – some frames are off-kilter, others slightly out of focus, views are sometimes partially obscured by cars or branches, and a subtle slant to the right permeates many. It’s as if Stone captured these images in a hurried manner, snapping shots on the go as he walked down the sidewalk.

Considering Norfolk Street’s understated character, Stone’s fleeting, slightly off-kilter photographs resonate deeply. They evoke the feeling of being in motion, mirroring the quick glances one might take while passing through Norfolk Street. The tilt in the images amplifies this sense of constant movement. Through this subjective, documentary style, Stone effectively communicates the essence of Norfolk Street as he perceived it.

Stone’s photographic interpretation aligns with the reality of Norfolk Street. Compared to the vibrant restaurants and shops lining its intersecting streets, Norfolk appears almost stark. It’s like the introverted sibling in a family of extroverts, quietly existing in the shadow of its more attention-grabbing counterparts. But Norfolk, in its unassuming nature, doesn’t seem to mind. It patiently waits for those who are willing to slow down, to turn their attention and curiosity its way. At first glance, it may seem unremarkable – just five blocks of brick tenements, schools, and stretches of parking lots. However, the key to appreciating this and other seemingly “ordinary” parts of the city is to look beyond the surface.

Norfolk Street boasts a surprisingly rich history, marked by periods of both prosperity and decline. Like the broader Lower East Side, Norfolk Street was a hub of activity and life at the turn of the 20th century, populated by waves of immigrants seeking new opportunities in America. While numerous photographs depict the era’s living conditions and atmosphere, novelist Meredith Tax provides a particularly vivid portrayal of the Norfolk Street vicinity in her novel, Rivington Street: A Novel. Tax’s extensive research into the lives of early 20th-century Jewish families in the Lower East Side lends historical authenticity to her fictional narrative. Through her character, Hannah, navigating the LES streets, Tax offers readers a unique, “first-hand” glimpse into life around Norfolk Street in the early 1900s:

Taking her shopping bag and plunging into the life of the marketplace, Hannah threaded her way along the choked sidewalks—six hundred people on every acre of the East Side, more packed even than China. Stalls and awnings burst from the tiny shops onto the sidewalks, pullers-in hollered and grabbed her arm as she went by, pushcarts encroached upon the sidewalk from the other side, leaving almost no passageway.

And here was the world of her delight, after six years still as thrilling to her as an Arabian Nights bazaar. The filth, the crush, the stink, the cacophony of a thousand bickering voices, the yelling of children underfoot, the countless peddlers shouting their wares: pickle vendors with their vats of sours, gherkins, green tomatoes; candymen and their lollipops, licorice sticks, squares of butterscotch ten for a penny; the halvah man and the woman with slabs of broken chocolate. There were carts heaped with dried fruits and nuts—baseball nuts, polly seeds, St. John’s potatoes from little metal ovens on wheels; and a fellow how cried ‘Hot chickpeas! Roasted chickpeas!’ Chicken and geese hung by their necks from poultry carts and fish were piled one upon the other, staring upward with glassy eyes. A man peddled hot ears of corn from a vat perched on a baby carriage. Another sold political pamphlets; a missionary dispensed tracts; a vendor of Yiddish sheet music sang free samples; and three little boys practiced a vaudeville routine. There was even an ‘Irish tenor from Lithuania,’ singing in English the song of the hour, ‘I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now,’ with a cap in front of him.

She pushed through the crowded street. Look up and you could see the sweatshop workers hard at it, faces gray as the cloth that drained their lives little by little. Occasionally a worker came out onto one of the fire escapes to gasp for air and she gave him a rueful smile, remembering the lint that had filled her own lungs. The fire escapes were covered with bedding and mattresses, like low-hanging white clouds; clothes hung out to dry between the buildings were getting dirty over again from the air.

This passage immediately highlights the stark contrast between the Norfolk Street experience of today and its vibrant past, when it was teeming with people and bustling with commerce. Historical accounts often describe the Lower East Side in this era as intensely crowded, filled with street vendors and lively bartering. Tax’s novel, however, provides a richer, more visceral, and personalized understanding of the neighborhood’s atmosphere.

Subtle remnants of this vibrant past still exist on Norfolk Street for those who know where to look. Following the German Reform Movement in the mid-19th century, the Lower East Side witnessed a significant influx of German-Jewish immigrants. They established theaters, cafes, publishing houses, and synagogues throughout the neighborhood, including the Ansche Chesed synagogue, now located at 172 Norfolk Street. This synagogue, a landmark for over a century and a half, flourished alongside its community. However, by the 1960s, Norfolk Street, like many parts of the LES, faced challenges. Fires, rising crime rates, and business closures led to a period of decline. Fortunately, the Ansche Chesed synagogue was saved from demolition when developers purchased and boarded it up, anticipating the neighborhood’s eventual resurgence. In 1986, sculptor Angel Orensanz acquired the synagogue, embarking on a restoration project that revived its former splendor and transformed it into the Angel Orensanz Center, a venue for art exhibitions and performances.

Much like Norfolk Street itself, many establishments along the street possess a hidden depth, offering unique experiences without actively seeking attention. The Angel Orensanz Center is a prime example. During its renovation, Orensanz maintained the building’s unassuming facade, adding only simple metal sculptures to signal its new purpose as an art and performance space, rather than a place of worship. Yet, the building’s exterior belies its breathtaking interior. It’s a space grand enough to host the wedding of Sarah Jessica Parker and Matthew Broderick, a Lady Gaga album release event, and even scenes from the television series Gossip Girl (twice!). Beyond these high-profile events, the center functions as a full-time art gallery, showcasing works by Angel Orensanz and other artists. While no longer solely a place of worship, the Angel Orensanz Center continues to foster community, bringing people together through shared appreciation of the arts.

The Angel Orensanz Center represents a success story for Norfolk Street, yet not all of the street’s historical establishments have enjoyed such positive outcomes. The Beth Hamedrash Hagodol synagogue, located at the corner of Norfolk and Broome Streets, served as another significant place of worship in the neighborhood during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, drawing diverse congregations to Norfolk Street. In the late 1800s, it housed a large and thriving community, with a dedication ceremony so well-attended that the street outside was “packed from curb to curb” with people eager to witness the event, even exceeding the synagogue’s capacity. Sadly, the Beth Hamedrash Hagodol synagogue has long been abandoned and has been in desperate need of repair funding since the 1940s. Though still standing at its original location, it is a mere shadow of its former glory.

A more recent Norfolk Street establishment met a similarly unfortunate fate. A few blocks north of the synagogues, at 107 Norfolk Street, stood a small, garage-like building. This unassuming brick cube, now empty, was once the cherished haven of some of the Lower East Side’s most talented underground musicians – Tonic.

Opened in 1998, Tonic quickly became a vital venue for New York City’s underground music scene. In keeping with Norfolk Street’s general aesthetic, Tonic was far from glamorous. The space was cramped, decidedly unrefined, and prone to both flooding and plumbing issues. Performers often had to improvise with makeshift stages, using card tables and spare chairs for equipment. But, like other notable places on Norfolk Street, Tonic embodied the street’s knack for concealing high-quality experiences behind unassuming exteriors. Despite its rough-around-the-edges atmosphere, people flocked to Tonic because of what it represented: the spirit of the “struggling artist,” a place where music itself was the sole focus. Uniquely, Tonic wasn’t dedicated to a specific genre but rather to musical integrity and the pure appreciation of music. It unexpectedly hosted performances by musicians who were already well-known or on the cusp of fame, including Sonic Youth, Norah Jones, Cat Power, and Yoko Ono. However, Tonic’s true heart lay in its eclectic mix of experimental jazz musicians like Martin, Medeski, and Wood, John Zorn, Ras Moshe, and Marco Benevento, who found an enthusiastic and receptive audience at the venue.

Initially, their music might sound like unstructured noise, but this distinctive, improvisational sound is a form of musical art, more akin to a stream of consciousness expressed through instruments than a conventional, pre-composed melody. It reflected the Tonic community’s counter-commercial ethos, a rejection of mainstream musical commodification and a desire to return music to its primal, emotional roots. The Tonic community used their music as a means of self-identification, creating a thriving subculture within this small Lower East Side garage, a space for rebellion against musical homogenization. Tragically, in 2007, the very forces Tonic resisted led to its demise. After nine years, Tonic was evicted due to unsustainable rent increases – a familiar narrative for numerous music venues across the neighborhood. While gentrification had been gradually displacing beloved LES music spots, Tonic’s closure was particularly painful. On its final day, over 100 musicians and fans gathered for a farewell performance. When police arrived to lock the doors, the crowd protested, leading to arrests. Even after its physical closure, Tonic’s community spirit lived on through the Tonic newsletter and a Facebook page where fans shared memories and photos from past shows.

While some Norfolk Street establishments have faced unfortunate economic pressures, those that remain today seem to have found a way to leverage the street’s relative obscurity. The cafes, restaurants, bars, and galleries on Norfolk Street may not be city-wide household names, but they consistently offer unique and high-quality experiences, as evidenced by online customer reviews. My personal favorite is Tiny’s Giant Sandwich Shop, a tiny corner cafe at Norfolk and Rivington, something of a hidden gem among New York City cafe aficionados. Schiller’s Liquor Bar is perhaps the most “famous” restaurant on Norfolk, known for its relaxed ambiance, excellent food at reasonable prices, and even a cameo in the 2010 romantic comedy Morning Glory. Norfolk Street truly comes alive after dark, with basement bars seemingly appearing from nowhere as evening descends and artificial lights illuminate the street. The Back Room, for instance, cleverly disguises itself as a slightly spooky, vintage toy store, with a “Lower East Side Toy Co.” sign above its entrance. It operates as a speakeasy-style bar with a clandestine vibe – access feels exclusive, requiring a certain insider knowledge. Even more exclusive is the back room within the Back Room, reserved for friends and acquaintances of the owners.

In my explorations of Norfolk Street, I’ve discovered its talent for keeping its best aspects subtly hidden, revealing them only to those who invest the time to explore beyond the surface and seek out interesting finds in unexpected places. Looking at Norfolk Street superficially, you’d hardly expect it to be a recurring filming location for Gossip Girl, a celebrity wedding venue, or a favorite spot for pop culture icons like Lady Gaga. It’s not the iconic, neon-drenched, bustling New York street of popular imagination. Instead, it’s quiet, often deserted during the day, and possesses a slightly edgy feel. Yet, it holds numerous hidden treasures waiting to be discovered and has a remarkable ability to foster communities around shared interests and passions. These very qualities are what contribute to Norfolk Street’s unique allure.

Works Cited

http://www.nysonglines.com/norfolk.htm

Click to access orensanz-booklet.pdf

http://www.archives.nysed.gov/a/research/res_topics_pgc_jewish_essay.shtml

http://www.orensanz.org/angel.html

“Synagogue Needs $35,000: Beth Hamedrash Hagodol Must Repair Building Defects.” New York Times [New York] 30 Dec. 1946. Print.

“DEDICATING A SYNAGOGUE. The New House Of The Congregation Beth Hamedrash Hagodol.” New York Times [New York] 17 Aug. 1885. Print.

Tax, Meredith. “Chapter II.” Rivington Street: a Novel. Urbana: University of Illinois, 2001. 81-83. Print.

“Morning Glory Film Locations – On the Set of New York.com.” Film Locations. Web. 25 Oct. 2011. http://onthesetofnewyork.com/morningglory.html>.

Sisario, Ben. “Avant-Garde Music Loses a Lower Manhattan Home.” The New York Times[New York] 31 Mar. 2007. Print.

Chinen, Nate. “Requiem for a Club: Saxophone and Sighs.” The New York Times [New York] 16 Apr. 2007. Print.

Corbould, Clare. “Streets, Sounds and Identity in Interwar Harlem.” (2006). Web.

“”Drugstore Photographs, Or, A Trip Along the Yangtze River, 1999;” Lower Manhattan Block-by-Block by Dylan Stone.” NYPL Digital Gallery. New York Public Library. Web. 19 Nov. 2011. http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/explore/?col_id=176>.

Unveiling the History of Norfolk Street: From Immigrant Enclave to Modern Enigma

Norfolk Street, a seemingly ordinary thoroughfare in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, extends from East Houston Street south to Grand Street. Paralleling Essex and Suffolk Streets, its name, like theirs, originates from a county in southeastern England, a nod to colonial history (Naureckas). Despite its English namesake, Norfolk Street’s character has been profoundly shaped by German and Eastern European Jewish immigrants who infused it with their cultures. Their legacy is visible in two landmark synagogues: Ansche Chesed (now the Angel Orensanz Center), established in 1849 by German Jewish immigrants, and Beth Hamedrash Hagodol, built in 1852 by Eastern European Jewish communities (Orensanz, Sussman).

Perhaps the most compelling lens through which to understand Norfolk Street’s history is the story of the Ansche Chesed synagogue, a presence for over 150 years. In the mid-19th century, the German Reform Movement spurred a wave of German-Jewish immigration to the Lower East Side, bringing with them new cultural expressions, philosophical ideas, musical traditions, and innovative concepts. The neighborhood flourished with theaters, cafes, publishing houses, and synagogues, including Ansche Chesed, whose opening ceremony was attended by New York’s governor and mayor, signifying Norfolk Street’s prominence and vitality at the time. However, by the 1960s, Norfolk Street experienced a downturn. Fires, increased crime, and business closures led to urban decay. Developers acquired the synagogue, boarding it up to await the neighborhood’s anticipated revitalization. During this period of LES decline, artists began to reclaim vacant spaces, gradually transforming the area back into a cultural and intellectual hub. While the Ansche Chesed synagogue remained neglected, the surrounding area was stirring with renewed energy. In 1986, sculptor Angel Orensanz purchased the synagogue from the developers, embarking on a restoration that revived its former glory. He transformed it into the Angel Orensanz Center, an acclaimed venue for art exhibitions and performances. The center has since hosted numerous high-profile events, including fundraisers for non-profits and celebrity weddings (The Farber Center). Notably, Norfolk Street is now home to several independent art and fashion galleries. While no longer as bustling as in its past, Norfolk Street retains a quiet artistic and sophisticated spirit. The street also features Sloan Fine Art, NORFOLKSNYC, Gallery One Twenty Eight, the L.E.S. Runway, and the Thierry-Goldberg Gallery, along with the Asian American Arts Centre. Interspersed among these cultural spaces, particularly at Norfolk’s southern end, are locally owned, unassuming businesses and restaurants, while the majority of the streetscape consists of classic brick apartment buildings.

Interior of the Angel Orensanz Center

Sources:

http://www.nysonglines.com/norfolk.htm

Click to access orensanz-booklet.pdf

http://www.archives.nysed.gov/a/research/res_topics_pgc_jewish_essay.shtml

http://www.orensanz.org/angel.html

http://thefarbercenter.com/blog/2010/07/21/the-venue-for-rocks-against-cancer/

Street Art and Hidden Messages: Decoding Norfolk Street’s Urban Canvas

At first glance, Norfolk Street may appear unremarkable – a quiet stretch of residential buildings and modest local businesses, seemingly just another street in the urban grid. However, as anyone familiar with New York City knows, initial impressions can be deceiving. Superficial observation often misses the hidden layers of interest and character that the city holds. (Of course, this deeper appreciation often comes at the cost of a slower pace, a luxury not always afforded in the city’s relentless rhythm.)

On a recent visit to Norfolk Street, I consciously slowed down, making an effort to truly see what I had previously overlooked. While Norfolk Street is home to several established art galleries, the street itself also serves as an informal canvas for the city’s more spontaneous artistic expressions. Graffiti adorns many buildings in the Lower East Side, but on Norfolk Street, I encountered particularly striking and thought-provoking pieces.

Street art on Norfolk Street featuring paired faces and multilingual message of friendship.

One spray-painted artwork stood out: it depicted four rows of faces – diverse in gender and ethnicity – facing each other in profile, arranged in pairs. Interspersed between these rows were the words “Friendship starts with good communication,” rendered in English, Spanish, and Chinese characters.

Close-up of the multilingual graffiti art on Norfolk Street emphasizing intercultural communication.

This artwork resonated as a poignant representation of Norfolk Street and the city at large. While Norfolk Street and its surroundings have deep roots in European Jewish immigrant history, it, like New York City itself, has evolved into a vibrant tapestry of diversity. A significant Chinese community now thrives on Norfolk Street, alongside traditional American eateries and even a high-end Eastern European bistro, a subtle echo of Norfolk Street’s early immigrant history. This diversity extends beyond ethnicity to encompass lifestyles, interests, and ideologies. Modern glass condominiums stand adjacent to historic brick tenements, and a contemporary fine arts center operates within a 19th-century German synagogue. Graffiti, by its very nature, is inextricably linked to its environment. This particular artwork, painted directly onto a building at Norfolk Street’s midpoint, should be viewed within the context of the street as a whole: a quiet side street that embodies a unique blend of history, artistic subcultures, immigrant experiences, and classic American diners. This artwork prompts reflection: is it suggesting that Norfolk Street, in its unassuming way, serves as a microcosm, a slightly imperfect but functional model for a society striving for peaceful coexistence? Norfolk Street is far from a glamorous Manhattan avenue, but it does possess an atmosphere of quiet harmony, a quality many places could learn from.

A quick online search reveals that this “Friendship starts with good communication” graffiti piece has been a fixture for quite some time, at least in street art terms. Photos of the artwork date back to 2006. Furthermore, comparing photographs from different periods suggests that the piece is regularly maintained, with any encroaching tags from other artists being removed. Consider these images alongside my own:

Graffiti art on Norfolk Street photographed in April 2007 by Pavla Kopecna, showing consistent maintenance over time.

Image of the same graffiti from June 2010 by Shira Lazar, illustrating ongoing upkeep of the street art.

Image of the same graffiti from June 2010 by Shira Lazar, illustrating ongoing upkeep of the street art.

Whether commissioned by a local business or created by an anonymous street artist, the artwork’s message clearly resonates, as those responsible for the building’s upkeep have chosen to preserve it as an integral part of the streetscape.

Experiencing Norfolk Street on Foot: A Walk Through the Unassuming

Norfolk Street isn’t typically a street one traverses from end to end, unless it happens to be the most direct north-south route between Houston and Delancey. Yet, having walked its entire length numerous times, I still experience a slight sense of self-consciousness, as if I’m engaging in an activity not quite intended for this space.

Despite its historical buildings and small art galleries, Norfolk Street doesn’t project itself as a “destination.” Primarily, it’s a corridor of quiet apartment buildings, lacking the enticing shop windows or captivating sights that encourage lingering, save for the occasional piece of street art. The feeling of walking on Norfolk Street, rather than simply through it, is somewhat peculiar. For most, Norfolk Street appears to be primarily a conduit between more active neighboring streets. During a Tuesday morning visit, Norfolk Street was noticeably more animated than during previous afternoon explorations. Residents were walking dogs, presumably before work or school; staff at Schiller’s Liquor Bar and Remedy Diner were opening up for the day; and commuters were briefly stopping at Tiny’s Giant Sandwich Shop’s walk-up window for coffee. (Notably, these businesses are all located on corners.) Walking north to south, I observed that most pedestrian traffic flowed horizontally, along Norfolk’s intersecting streets, particularly Rivington and Stanton. My perpendicular path felt somewhat out of sync, requiring frequent yielding and maneuvering at corners. The impression persisted: I was lingering on a street not meant for lingering, a street primarily used for transit. This makes sense, as Norfolk Street, compared to the abundance of restaurants and shops on its cross streets, is relatively bare. It offers little to a New Yorker on a typical Tuesday morning commute. Reflecting on de Certeau’s concept of walking as a form of language, Tiny’s Sandwich Shop, situated at the corner of Norfolk and Rivington, becomes symbolic. Its main entrance faces Rivington, inviting the heavy pedestrian flow to step inside, while its Norfolk-facing side offers only a walk-up window for quick orders, facilitating swift continuation of one’s journey. While Norfolk Street is part of many routes, few pause there for long; it doesn’t seem designed for extended stays, at least not on a weekday morning.

It’s as if Norfolk Street is the introverted sibling, quietly overshadowed by its more attention-grabbing counterparts. Yet, Norfolk, in its unassuming way, doesn’t seem to mind. It quietly waits for the daily rush to subside, for moments when people have time to direct their curiosity its way. Its atmosphere of quiet artsiness, previously noted, remains constant. While not a destination street in the conventional sense, I imagine it fosters serendipitous discoveries, perhaps on weekends or evenings, when people wander without a fixed agenda, turning onto Norfolk Street and finding themselves charmed by its small galleries and eateries. But a busy Tuesday morning is not such a time.

Norfolk Street’s Darker Chapters: Unearthing a Victorian Era Past

While many of its historic tenement buildings still stand, Norfolk Street has long shed the crowded, bustling, and chaotic atmosphere that defined the Lower East Side in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A brief foray into historical New York Times archives reveals that Norfolk Street’s history offers a captivating glimpse into daily life in Victorian Era Manhattan.

Particularly during this period, Norfolk Street attracted diverse crowds due to its religious institutions, most notably Beth Hamedrash Hagodol, the Jewish synagogue still located at the corner of Norfolk and Broome Streets. Though sadly now derelict and in need of restoration funding since the 1940s(¹), in the late 1800s, it was a thriving congregation center, hosting a grand dedication ceremony on August 16, 1885. The street outside overflowed, “packed from curb to curb” with people “endeavor[ing] to get into the synagogue to witness the dedication services,” exceeding even the synagogue’s standing-room capacity(2). Further north, the Anshi Chesed synagogue (now the Angel Orensanz Center) also held regular services in German(3). Norfolk Street was also a lively commercial hub, with street vendors operating carts along its length, leading to occasional conflicts, such as a reported fistfight between two vendors over a horse eating apples from a neighboring cart!(4).

Despite this somewhat domestic and religiously anchored atmosphere, Norfolk Street also witnessed darker events, including vendor brawls, “Wild West-style” saloon robberies, and unsettling suicides and murders. In 1912, Norfolk Street was the scene of two particularly gruesome murders reminiscent of London’s Jack the Ripper. An elderly couple at 101 Norfolk Street were found tortured and killed in their apartment, “a sharp instrument having been driven through the eyes of the old couple into their brains.” The perpetrator was believed to be a “religious fanatic,” but the crime remained unsolved(5,6). These unusually brutal murders drew national attention to Norfolk Street for days, prompting newspaper coverage across Pennsylvania, Missouri, Massachusetts, and Washington, D.C. This era also coincided with Prohibition, and newspaper articles detailed raids and arrests for illegal alcohol stashes, including one instance where a man at 81 Norfolk Street was caught running a printing press in his home to counterfeit revenue stamps for illicit liquor sales(7).

[Illustration accompanying the New York Times article about the murder of the elderly couple on Norfolk Street]

Norfolk Street’s past is far more multifaceted than initially apparent. My next walk down Norfolk Street will undoubtedly be colored by these historical accounts – visions of women haggling with vendors, families heading to synagogues, and, at night, inebriated men leaving saloons and shadowy figures lurking in the darkness. Some of the present-day tenement buildings likely stood a century ago, yet the atmosphere surrounding them has drastically changed. The vibrancy, clamor, and color of the past are largely absent; Norfolk Street today is a quiet, somewhat overlooked street whose present ambiance belies its fascinating history. The poignancy lies in the lack of overt reminders of this past on the street itself, save for the synagogues and their stories. As Crang wrote in “Envisioning Urban Histories,” “History does not form a presence on the scene but an absence and loss or, rather, a ghostly presence that haunts the city–not life as it was but life as it has been forgotten”(8).

Works Cited:

- “Synagogue Needs $35,000: Beth Hamedrash Hagodol Must Repair Building Defects.” New York Times [New York] 30 Dec. 1946. Print.

- “DEDICATING A SYNAGOGUE. The New House Of The Congregation Beth Hamedrash Hagodol.” New York Times [New York] 17 Aug. 1885. Print.

- “Sermon by Rev. A. Berky, Pastor of the German Reformed Protestant Dutch Church, in Norfolk-Street, Near Stanton.” New York Times [New York] 27 Nov. 1863. Print.

- “HIS HORSE LIKED APPLES. Because of His Taste Owner Gottlieb Is Charged with Assault.” New York Times [New York] 15 Aug. 1893. Print.

- “AGED COUPLE ARE TORTURED TO DEATH: Bodies of Rich Manufacturer and Wife Are Found Terribly Mutilated.” New York Times [New York]. Print.

- “OLD COUPLE SLAIN; DAUGHTER DETAINED.” New York Times [New York] 8 Jan. 1912. Print.

- “BOGUS RUM STAMPS ARE SEIZED IN RAID: Outfit for Engraving and Printing Revenue Certificates Found in Norfolk Street Room.” New York Times [New York] 26 Mar. 1921. Print.

- Crang, M. “Envisioning Urban Histories: Bristol as Palimpsest, Postcards, and Snapshots.”Environment and Planning A. Vol. 28. 429-52. Print.

Norfolk Street Demographics: A Historical Population Shift

While specific historical demographic data for Norfolk Street itself is scarce, examining the broader demographic trends of the street and its surrounding area provides insights into the evolving population of Norfolk Street over the past 250 years. (Detailed census data is most readily available from 1850 onward. 1850 marked a significant shift in US census-taking, as it was the first year the Census Bureau attempted to enumerate every individual in each household, including women, children, and enslaved people, rather than just heads of households. Pre-1950 data primarily provides information for New York City as a whole, but this broader context still informs our understanding of the Norfolk Street area.)

In 1850, New York City had become a major commercial and industrial center in the wake of the Industrial Revolution. Population density was already high, ranging from 15,000 to 22,455 people per square mile. The largest age group was 20-39 years old, likely reflecting migration to the city for work opportunities. The gender balance was relatively even, with slightly more women than men. New York City was experiencing significant immigration, primarily from white European countries. Foreign-born residents constituted 40-60% of the city’s population, while non-white residents comprised only 1-5%. While specific immigrant origins aren’t detailed in the Social Explorer demographic maps for this period, this aligns with historical accounts of German and Eastern European immigration to the Norfolk Street area in the mid-1800s.

Map of foreign-born population density in New York City in 1850, illustrating immigrant concentrations.

Map of white population density in New York City in 1850, showing dominant demographic group.

Legend for the 1850 white population map, indicating population density ranges.

By 1900, New York City’s population had more than doubled, with density increasing from a maximum of 22,500 people per square mile in 1850 to 47,727 per square mile. Immigrants still constituted roughly half the city’s population, and the growth of second-generation immigrant families was evident – native-born whites of foreign parentage outnumbered native-born whites of native parentage. 1900 census data provides origin details: the largest immigrant groups were from Ireland, Italy, and, consistent with historical research, Germany and Russia.

In 1950, census data became more geographically specific and detailed. The population density of the Norfolk Street area reached approximately 112,000 people per square mile. For the first time in this data, the male population exceeded the female – previously, women slightly outnumbered men, but in 1950, men were 45-70% more numerous! Interestingly, male population density was particularly high on the west side of Norfolk Street.

Map of male population density in the Norfolk Street area in 1950, highlighting gender imbalance.

Legend for the 1950 male population map, showing density ranges for male residents.

The area was predominantly low-income; the largest segment earned $500 or less annually. Most households were married couples without children, and buildings were overwhelmingly renter-occupied. The largest occupational category was “operatives,” likely indicating manufacturing or related jobs. Immigration slowed, and the native-born population surpassed the foreign-born for the first time in the studied period.

By 2000, population density remained high, though peak density slightly decreased to 230,000 people per square mile. Age distribution remained consistent across age groups from 18 to 54. The female population again slightly outnumbered males. The population remained primarily white, but the gap between white and non-white populations narrowed significantly, with whites constituting 40-60%. The area’s economic profile changed dramatically. While previously low-income, average household income rose to $75,000-$100,000, a substantial increase. Households were still primarily married couples without children. Foreign-born population remained high, 30-40%, predominantly of Asian origin.

Works Cited:

Norfolk Street in Fiction: A Glimpse into 1909 Lower East Side Life

Finding fictional works specifically set on Norfolk Street proved challenging. However, broadening the search to novels mentioning neighboring streets revealed a literary treasure: Rivington Street: A Novel by Meredith Tax (1982). This historical fiction novel portrays a Jewish family’s adaptation to New York City life after fleeing pogroms in early 20th-century Russia.

In one chapter, Tax vividly describes the area around the Levy family’s apartment at the corner of Rivington and Essex Streets – just a block from Norfolk Street. The chapter opens with Hannah Levy reveling in her “new-found freedom” and achieving “her dream: a flat on a good block, Rivington and Essex, in a corner building, a new-law tenement with running water in every kitchen and a toilet on each landing” (Tax 81). Looking out her window, she observes the bustling streets: “She surveyed her kingdom, the teeming street. A melting pot they called it, but it was more like a boiling soup kettle, swirling round and round in ceaseless motion. You could never tell what might come to the surface, and her eyes strained perpetually for fear of missing something” (Tax 81). She then takes the reader downstairs and into the neighborhood marketplace:

Taking her shopping bag and plunging into the life of the marketplace, Hannah threaded her way along the choked sidewalks—six hundred people on every acre of the East Side, more packed even than China. Stalls and awnings burst from the tiny shops onto the sidewalks, pullers-in hollered and grabbed her arm as she went by, pushcarts encroached upon the sidewalk from the other side, leaving almost no passageway.

And here was the world of her delight, after six years still as thrilling to her as an Arabian Nights bazaar. The filth, the crush, the stink, the cacophony of a thousand bickering voices, the yelling of children underfoot, the countless peddlers shouting their wares: pickle vendors with their vats of sours, gherkins, green tomatoes; candymen and their lollipops, licorice sticks, squares of butterscotch ten for a penny; the halvah man and the woman with slabs of broken chocolate. There were carts heaped with dried fruits and nuts—baseball nuts, polly seeds, St. John’s potatoes from little metal ovens on wheels; and a fellow how cried ‘Hot chickpeas! Roasted chickpeas!’ Chicken and geese hung by their necks from poultry carts and fish were piled one upon the other, staring upward with glassy eyes. A man peddled hot ears of corn from a vat perched on a baby carriage. Another sold political pamphlets; a missionary dispensed tracts; a vendor of Yiddish sheet music sang free samples; and three little boys practiced a vaudeville routine. There was even an ‘Irish tenor from Lithuania,’ singing in English the song of the hour, ‘I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now,’ with a cap in front of him.

She pushed through the crowded street. Look up and you could see the sweatshop workers hard at it, faces gray as the cloth that drained their lives little by little. Occasionally a worker came out onto one of the fire escapes to gasp for air and she gave him a rueful smile, remembering the lint that had filled her own lungs. The fire escapes were covered with bedding and mattresses, like low-hanging white clouds; clothes hung out to dry between the buildings were getting dirty over again from the air.

Tax’s extensive research into early 20th-century Lower East Side Jewish life lends historical weight to her fictional depiction. Through Hannah’s experiences, readers gain a unique “first-hand” perspective on life in the Norfolk Street area in the early 1900s. The phrase “Look up and you could see” creates a sense of guided tour, immersing the reader in the scene. While photographs capture similar scenes, Tax’s prose provides a uniquely sensory experience – the clamor of vendors, the smells of food, the physical press of crowds. While countless accounts describe the Norfolk Street area as crowded and bustling, Tax’s novel offers a richer, grittier, and more personal portrayal. It underscores the profound transformation of Norfolk Street from a vibrant, teeming hub to its present-day quietude. Only its racial and cultural diversity seems to bridge the past and present. Walking Norfolk Street after reading Tax’s novel evokes a surreal feeling – imagining this now-understated street as a perpetual street fair.

Rivington Street in 1910, a neighboring street to Norfolk Street, showcasing the bustling Lower East Side atmosphere of the era. (Courtesy of NYPL Digital Gallery)

(Click the image to view in full size.)

Works Cited:

- Tax, Meredith. “Chapter II.” Rivington Street: a Novel. Urbana: University of Illinois, 2001. 81-83. Print.

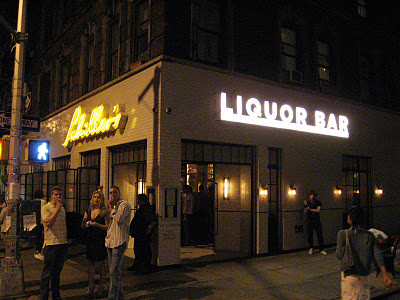

Norfolk Street on the Silver Screen: Schiller’s Liquor Bar in “Morning Glory”

While expecting to find little cinematic representation of Norfolk Street, I was surprised to discover that a restaurant on the street was featured in a recent mainstream comedy film.

Morning Glory, released in 2010, is a comedy-drama-romance in the vein of The Devil Wears Prada (written by the same screenwriter). Instead of the fashion world, it focuses on the pressures of live television production. Rachel McAdams stars as Becky Fuller, an ambitious but awkward producer hired to revive the struggling morning show Daybreak. Becky, an unwavering optimist, aims to revitalize the program, but faces resistance from the cynical Daybreak cast and crew. Through perseverance, she learns to navigate these personalities, bends some morning show conventions, reunites the team, revitalizes the show, secures a dream job offer, and finds romance.

Early in her Daybreak tenure, Becky befriends Adam Bennett (Patrick Wilson), a producer for another show in the same building. Adam invites Becky for drinks after work: “So, now is an excellent time for you to take up drinking, and I came by to say that sometimes after work a few of us go over to Schiller’s on Madison, so, um, you know, if you’re, uh, ever… around…”

The name “Schiller’s” was immediately recognizable. Schiller’s Liquor Bar is not on Madison Avenue, but on the corner of Norfolk and Rivington Streets. (I’ve spent considerable time observing its neon “LIQUOR BAR” sign while brainstorming blog post ideas at the cafe across the street!)

Later, Becky, in Bryant Park with friends, sees Adam walking towards (the fictional) Schiller’s on Madison. She follows him, and the film shows the actual Schiller’s Liquor Bar on Norfolk Street. The film’s portrayal captures Schiller’s atmosphere – trendy, relaxed, and lively. When Becky leaves, the film showcases Schiller’s exterior: the angled corner entrance, white brick walls, and retro neon sign. The shot is from the Norfolk Street side, and the street is depicted as far busier than it typically is in the afternoon – understandably, as it’s standing in for Madison Avenue! While Schiller’s Liquor Bar is popular, Norfolk Street is rarely that crowded during the day.

[Schiller’s Liquor Bar exterior, from Norfolk Street]

[Schiller’s interior shots]

Schiller’s Liquor Bar interior as depicted in “Morning Glory,” showcasing its trendy and relaxed atmosphere.

Films often take liberties with location accuracy. Schiller’s is far from Madison Avenue, but the film cleverly suggests it’s a short walk from Bryant Park. Initially, the relocation seemed puzzling. However, it likely reflects a deliberate choice about character portrayal. In film, the Lower East Side is often associated with struggling artists and a bohemian lifestyle, while Morning Glory‘s characters are ambitious, upwardly mobile television professionals. Having them frequent a Lower East Side bar would be incongruous with their character profiles. Their preferred haunts would be hip, upscale bars in equally upscale locations – not a modestly graffitied street like Norfolk.

In movies, restaurants are often “placed” on well-known streets like Madison Avenue for instant recognition. Street names like Fifth Avenue, Broadway, Madison Avenue, Park Avenue, and Wall Street are cinematic shorthand for “New York.” Naming a less familiar street like Norfolk might detract from the film’s essential “New Yorkness.” Many New York residents, let alone those outside the city, are unfamiliar with Norfolk Street.

Works Cited:

- Morning Glory. Dir. Roger Michell. Perf. Rachel McAdams, Patrick Wilson, Harrison Ford, Diane Keaton, Jeff Goldblum. Bad Robot, Goldcrest Pictures, 2010. Digital Copy.

- “Morning Glory Film Locations – On the Set of New York.com.” Film Locations. Web. 25 Oct. 2011. http://onthesetofnewyork.com/morningglory.html>.

- “Morning Glory (2010) – IMDb.” The Internet Movie Database (IMDb). Web. 25 Oct. 2011. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1126618/>.

Norfolk Street After Dark: A Hidden Nightlife Destination

Walking Norfolk Street at night offers a starkly different experience. Expecting the usual daytime pattern – people passing through to reach establishments on Houston, Stanton, and Rivington, or lingering only at Schiller’s – I was surprised to find a vibrant nightlife scene emerging.

Unlike its daytime quietude, Norfolk Street unexpectedly transforms into a destination after dark. While during the day it’s largely deserted or used for transit, Saturday evening revealed a street surprisingly alive. Groups of friends filled Remedy Diner and Schiller’s Liquor Bar, people congregated on corners smoking and chatting, and couples strolled arm-in-arm, exploring the street’s underground bars. Music pulsed from restaurants and basement venues. The street’s darkness seemed to draw people toward these pockets of light and convivial atmosphere.

Patrons gathered outside Schiller’s Liquor Bar on Norfolk Street at night, illustrating its evening popularity.

Many Norfolk Street establishments operate on a “double life” pattern: quiet and unassuming during the day, but vibrant after sunset. Some bars, unnoticed during daylight, only become apparent at night when artificial lights illuminate their entrances. The Back Room, disguised as a spooky vintage toy store (“Lower East Side Toy Co.” sign included), revealed itself as a bar only upon closer inspection.

The Back Room on Norfolk Street during the day, its toy store facade concealing a hidden bar.

The Back Room on Norfolk Street during the day, its toy store facade concealing a hidden bar.

While bars and restaurants buzzed with activity, the rest of the street remained dominated by dark tenement buildings with rusted fire escapes and blank brick walls. Moving further south, fewer businesses and people were visible, and the atmosphere felt increasingly less safe. Delancey Street seemed to bisect Norfolk into two distinct sections. Delancey itself was bright and busy, but south of it, Norfolk Street – with its dark parking lots, dilapidated synagogue, and shadowy park – felt ominous compared to the livelier blocks to the north. Walking Norfolk Street at night became an experience of moving between zones of perceived safety and vulnerability.

Nightfall seemed to amplify Norfolk Street’s contrasting character. During the day, it’s uniformly quiet and still, but at night, shadier areas felt more menacing, while lively corners were more vibrant than ever.

Gossip Girl’s Norfolk Street Connection: Angel Orensanz Center as a Filming Location

While Norfolk Street itself remains low-profile, the Angel Orensanz Center (formerly Ansche Chesed synagogue) has attracted high-profile attention over the years. Known for hosting celebrity weddings and galas, it’s unsurprising that it has twice served as a filming location for Gossip Girl. In “The Witches of Bushwick” episode, Chuck Bass throws a lavish “saints and sinners” party, filmed inside the synagogue – a fitting choice given its event-hosting function.

Intriguingly, the show’s use of the location mirrored reality. The Angel Orensanz Center is available for event rentals, making it a plausible venue for a party like Chuck Bass’s. Interior shots closely resembled photos from actual Angel Orensanz events:

[Screencaps from “The Witches of Bushwick”:]

[Photos of actual events that took place at the Angel Orensanz Center:]

However, the show still locates the venue in a different part of the city. Flyover shots of the Empire State Building and Times Square suggest a Midtown setting, not the Lower East Side. Similar to Schiller’s Liquor Bar’s “relocation” to Madison Avenue in Morning Glory, this likely serves logistical and cultural purposes. Chuck Bass, a hotel owner and financier known for sharp suits, hosting a lavish ball on Norfolk Street seems incongruous with his character. Brief glimpses of the street outside in the show reveal exterior shots filmed elsewhere, likely on a bright, busy Midtown street, not quiet, dark Norfolk Street.

A brief glimpse of the street outside the party venue in “Gossip Girl,” filmed elsewhere to suggest a Midtown location.

A different church exterior was even used; the Angel Orensanz’s distinctive multicolored facade and metal sculptures were likely deemed too eccentric for the party’s sleek, sophisticated aesthetic.

Despite Norfolk Street’s low profile, the Angel Orensanz Center has hosted significant celebrity events. The street, largely modest and somewhat run-down, contains this pocket of celebrity activity. It’s a disparity that warrants further exploration.

Remembering Tonic: Norfolk Street’s Lost Underground Music Haven

At 107 Norfolk Street, a small brick building stands awkwardly between towering modern structures. Now empty, this building was once Tonic, a cherished haven for the Lower East Side’s underground music scene.

Tonic opened in 1998 and became a vital venue for New York City’s underground music. Cramped and unglamorous, prone to flooding and plumbing issues, with makeshift stages, Tonic prioritized music above all else. It embodied the “suffering artist” ethos. It wasn’t genre-specific but dedicated to musical integrity and appreciation. A diverse range of music, from folk to grunge to blues, could be heard on consecutive nights. Well-known musicians like Sonic Youth, Norah Jones, Cat Power, and Yoko Ono graced its stage, but its core was experimental jazz musicians like John Zorn, Marco Benevento, Ras Moshe, and Medeski, Martin, and Wood.

Their improvisational “noise” was a distinct musical art form, a stream of consciousness in sound, reflecting the Tonic community’s anti-commercial stance and desire to return music to its emotional core. Like Harlem’s black community using sound for self-definition, Tonic’s community used music to create a subculture, a haven against musical homogenization. This spirit of musical integrity united diverse music fans.

Tragically, in 2007, commercial pressures led to Tonic’s closure. Rent hikes forced eviction after nine years, a common fate for LES music venues. Tonic’s loss was deeply felt. On its closing day, over 100 musicians and fans gathered for a farewell show, protesting the closure and leading to arrests. The Tonic community persisted online via the Tonic newsletter and Facebook page, keeping its spirit alive.

Works Cited

- Sisario, Ben. “Avant-Garde Music Loses a Lower Manhattan Home.” The New York Times[New York] 31 Mar. 2007. Print.

- Chinen, Nate. “Requiem for a Club: Saxophone and Sighs.” The New York Times [New York] 16 Apr. 2007. Print.

- Corbould, Clare. “Streets, Sounds and Identity in Interwar Harlem.” (2006). Web.

Dylan Stone’s Norfolk Street: Capturing the Essence in “Drugstore Photographs”

In 1999, photographer Dylan Stone initiated “Drugstore Photographs, or A Trip Along the Yangtze River, 1999,” exploring “the intersection of art and documentation” (“Lower Manhattan Block-by-Block by Dylan Stone”). The project used archival boxes, paintings, and photographs. Stone’s Lower East Side snapshot collection is extensive, with 26,000 images of street corners and buildings, accessible via the New York Public Library’s digital archive.

Stone’s photographs, encountered previously during visual research, always struck me as artistically distinct for documentary images. They possess a muted color palette and a deliberately awkward aesthetic – some are poorly framed, out of focus, obstructed, and subtly tilted. They evoke a sense of hurriedness, as if captured on the move.

[Image grid of Dylan Stone’s Norfolk Street photographs]

(Note: As I cannot access external websites to provide direct image URLs for the grid, you should insert the actual image URLs from the NYPL digital archive here, ensuring you select a representative sample of Stone’s photographs of Norfolk Street.)

[Image URL placeholder]

[Image URL placeholder]

[Image URL placeholder]

[Image URL placeholder]

[Image URL placeholder]

[Image URL placeholder]

[Image URL placeholder]

Considering Norfolk Street’s character as unassuming and often overlooked, Stone’s fleeting, awkward photographs feel fitting. Norfolk Street isn’t a destination for lingering; it’s a place of passage. Stone’s images convey this sense of motion, mirroring the fleeting glances one might take while walking quickly down Norfolk Street. The tilt enhances this feeling of movement. The photographs also feel timeless; their decade-plus age is not immediately apparent. They highlight Norfolk Street’s own timeless quality – largely unchanged in a decade, save for a few new buildings.

Stone’s “intersection of art and documentation” challenges the notion of objective documentation. He sought to capture the feeling of the LES, the lived experience of walking its streets. His Norfolk Street photos achieve this, conveying a personal, subjective experience.

This exemplifies cultural expression through media, as discussed by Miller in “Grove Street Grimm: Grand Theft Auto and Digital Folklore.” Digital media, like folklore, are “a form of expressive culture transmitted through intersubjective performance, ‘in which a group, and the individuals who constitute it, can discuss, convey, reinforce, alter, and otherwise play with the validity of a concept and their attitude toward it’ (Motz)” (Miller 280). Stone’s photographs express his personal experience of Norfolk Street, conveying not just a visual representation but also his feelings and perceptions of the street to viewers.

Works Cited:

- “”Drugstore Photographs, Or, A Trip Along the Yangtze River, 1999;” Lower Manhattan Block-by-Block by Dylan Stone.” NYPL Digital Gallery. New York Public Library. Web. 19 Nov. 2011. http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/explore/?col_id=176>.

- Miller, Kiri. “Grove Street Grimm: Grand Theft Auto and Digital Folklore.” Journal of American Folklore (2008). Print.

Share this:

Like Loading…