The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 stands as one of the most devastating acts of racial violence in American history, forever scarring the legacy of a once-thriving community known as Tulsa Black Wall Street. In a mere eighteen hours between May 31 and June 1, 1921, this vibrant hub of African American prosperity was systematically destroyed, leaving behind a trail of ashes, displacement, and profound injustice. While estimates vary, credible sources suggest that hundreds of lives were lost and over a thousand homes and businesses were reduced to rubble, effectively erasing what was then the nation’s second-largest Black community.

This horrific event, often referred to as the Tulsa Race Riot in historical accounts, unfolded during a period of intense racial animosity across the United States. The resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and the courageous resistance of African Americans against racial terrorism, particularly lynchings, formed the backdrop of this tragedy. Tulsa, Oklahoma, a city grappling with rapid growth and social tensions, became the stage for this eruption of violence.

By 1921, Tulsa boasted a population exceeding one hundred thousand, with a significant African American population of ten thousand residents. The heart of this community was the Greenwood District, a self-sufficient and dynamic neighborhood that embodied Black economic empowerment. Greenwood was a testament to Black entrepreneurship and community building, featuring two newspapers, numerous churches, a library branch, and a multitude of Black-owned businesses that catered to the needs and aspirations of its residents. This prosperity earned Greenwood the moniker “Black Wall Street,” a symbol of Black achievement in a segregated America.

However, beneath the surface of Tulsa’s booming economy and Greenwood’s success lay deep-seated racial tensions and social instability. The city struggled with high crime rates and vigilante justice. Just months before the massacre, in August 1920, a white teenager accused of murder was lynched by a white mob, highlighting the fragility of law and order and the racial biases within the city’s systems. The Tulsa police’s inaction during this lynching foreshadowed the inadequate response to the unfolding tragedy in Greenwood.

Eight months later, a seemingly minor incident involving Dick Rowland, a young African American shoeshiner, and Sarah Page, a white elevator operator, ignited the tinderbox of racial prejudice. The exact details of what transpired in the Drexel Building on May 30, 1921, remain unclear. The most widely accepted account suggests that Rowland accidentally stepped on Page’s foot in the elevator, causing her to scream.

The following day, the Tulsa Tribune, a local afternoon newspaper, sensationalized the incident, reporting that Rowland had been arrested for allegedly attempting to rape Page. Fueling the flames of racial hatred, eyewitness accounts suggest that the Tribune also published a now-missing editorial titled “To Lynch Negro Tonight.” This inflammatory report, whether based on fact or rumor, incited a volatile atmosphere, and by evening, whispers of lynching once again filled the streets of Tulsa.

A photographer surveying the damage of the Tulsa Race Massacre in Greenwood, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

A photographer surveying the damage of the Tulsa Race Massacre in Greenwood, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

As dusk settled, the situation rapidly escalated. By 7:30 p.m., a large crowd of white men had gathered outside the Tulsa County Courthouse, demanding that Sheriff Willard McCullough hand over Dick Rowland. Sheriff McCullough, to his credit, refused to yield to the mob’s demands. Around 9 p.m., word of the escalating tensions downtown reached Greenwood. In a display of courage and community solidarity, approximately twenty-five armed African American men, many of them veterans of World War I, traveled to the courthouse to offer their assistance in protecting Rowland. Despite their noble intentions, the sheriff declined their offer, and the men returned to Greenwood.

The white mob, emboldened by the sheriff’s refusal to cooperate with the Black citizens and fueled by racial animosity, grew increasingly agitated. They attempted to raid the National Guard armory but were initially rebuffed by a small contingent of guardsmen. Around 10 p.m., a false rumor swept through Greenwood that white rioters were storming the courthouse. A larger group of African American men, this time numbering around seventy-five, returned to the courthouse, again offering their help to the authorities. Once more, they were turned away. As they were leaving, a confrontation occurred: a white man attempted to disarm a Black veteran, and a shot rang out. This single gunshot was the spark that ignited the Tulsa Race Massacre.

The ensuing six hours plunged Tulsa into unimaginable chaos. Frustrated by their inability to lynch Dick Rowland, the white mob unleashed their fury upon the entire African American community. Intense fighting erupted along the Frisco railroad tracks, where Black defenders valiantly but ultimately unsuccessfully attempted to hold back the surging white mob. In a chilling act of violence, an unarmed African American man was murdered inside a downtown movie theater. Carloads of armed white men began conducting drive-by shootings in Black residential areas, terrorizing families in their homes. By midnight, fires had been deliberately set on the edges of the Greenwood commercial district, signaling the impending destruction of Black Wall Street. In all-night cafes across the city, white men openly organized and planned a full-scale invasion of Greenwood at dawn.

In the initial hours of the massacre, local authorities were woefully inadequate in their response, if not complicit in the violence. Shortly after the shooting at the courthouse, Tulsa police officers deputized members of the white mob, effectively legitimizing their actions. Eyewitness accounts even suggest that police instructed these newly deputized men to “get a gun and get a nigger,” further fueling the racist violence. Local units of the National Guard were mobilized but prioritized protecting white neighborhoods from a nonexistent “Black counterattack,” leaving Greenwood undefended.

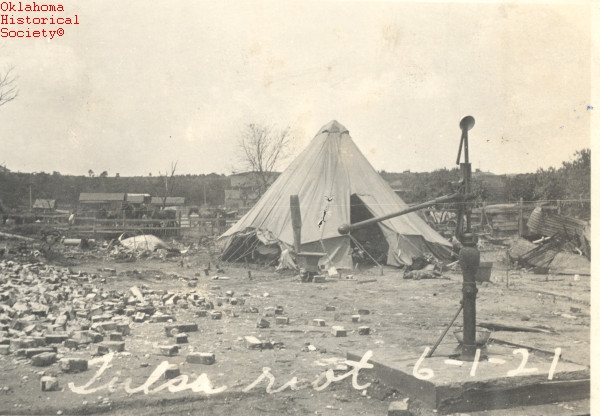

Victims of the Tulsa Race Massacre living in tents after their homes were destroyed in Greenwood, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Victims of the Tulsa Race Massacre living in tents after their homes were destroyed in Greenwood, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

As dawn broke on June 1, thousands of armed white men amassed on the borders of Greenwood, ready to execute their plan of destruction. With the first light of day, they stormed into the Greenwood District, systematically looting homes and businesses before setting them ablaze. The violence was brutal and indiscriminate. Numerous atrocities were committed, including the murder of Dr. A.C. Jackson, a renowned Black surgeon, who was shot dead after surrendering to a group of white men. Eyewitnesses and survivor accounts detail the use of at least one machine gun by the white attackers, and some claim that even airplanes were deployed to drop incendiary devices on Greenwood, though this remains a contested point.

The residents of Black Wall Street fought fiercely to defend their homes and their community. Particularly intense fighting took place around Standpipe Hill, a strategic high point in the district. However, the Black defenders were tragically outgunned and vastly outnumbered. By the time additional National Guard troops finally arrived in Tulsa at approximately 9:15 a.m. on June 1, the vast majority of Greenwood, the pride of Black Tulsa and a beacon of Black economic success, was already consumed by flames and reduced to ashes. Tulsa Black Wall Street was no more.

In the aftermath of the massacre, a brief period of martial law was declared, followed by a wave of recriminations and legal maneuvering. Despite the exoneration of Dick Rowland, an all-white grand jury, predictably, placed the blame for the violence squarely on the African American community. In a staggering miscarriage of justice, and despite overwhelming evidence of white culpability, no white person was ever convicted or imprisoned for the murders, arson, and widespread destruction that occurred in Greenwood.

The Tulsa Race Massacre left the vast majority of Greenwood’s African American residents homeless and destitute. Despite the efforts of the white establishment to prevent the rebuilding of Greenwood and force the relocation of the Black community, the resilient spirit of Black Tulsans prevailed. Within days of the devastation, they began the arduous process of rebuilding their lives and their community. However, thousands were forced to endure the harsh winter of 1921–22 living in tents, a stark reminder of the magnitude of their loss.

Victims of the Tulsa Race Massacre combing through the ruins of their homes and businesses in Greenwood, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Victims of the Tulsa Race Massacre combing through the ruins of their homes and businesses in Greenwood, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

The profound scars of the Tulsa Race Massacre remained visible for generations. While Greenwood was eventually rebuilt, it never fully regained its former glory, and many families never recovered from the economic and emotional devastation they endured. For decades, the Tulsa Race Massacre became a taboo subject, shrouded in silence and omitted from mainstream narratives, particularly within Tulsa itself.

In 1997, a state commission was finally established to investigate the Tulsa Race Massacre and to bring the truth to light. The commission’s report acknowledged the horrific events, documented the extent of the destruction, and recommended that reparations be paid to the remaining survivors and their descendants. Subsequent investigations, including archaeological studies, have uncovered evidence supporting long-held accounts of mass, unmarked graves containing the bodies of unidentified victims of the massacre.

The Tulsa Race Massacre, the destruction of Tulsa Black Wall Street, remains one of the most profound tragedies in American history. It serves as a stark reminder of the devastating consequences of racial hatred and systemic injustice. The story of Greenwood and its destruction is not just a local Oklahoma tragedy; it is a crucial chapter in the broader narrative of American race relations and the ongoing struggle for racial equality and justice. Remembering and understanding the Tulsa Race Massacre is essential for confronting the legacy of racial violence in America and working towards a more just and equitable future.

Further Reading:

- Ellsworth, Scott. Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1982.

- Franklin, John Hope, and Scott Ellsworth, eds. The Tulsa Race Riot: A Scientific, Historical and Legal Analysis. Oklahoma City: Tulsa Race Riot Commission, 2000.

- Gates, Eddie Faye. They Came Searching: How Blacks Sought the Promised Land in Tulsa. Austin, Tex.: Eakin Press, 1997.

- Parrish, Mary E. Jones. Events of the Tulsa Disaster. Tulsa, Okla.: Out on a Limb Publishing, 1998.

Online Resources:

- 100 Block North Greenwood Avenue, National Register of Historic Places: http://nr2_shpo.okstate.edu/QueryResult.aspx?id=SG100006631

- Vernon A.M.E. Church, National Register of Historic Places: http://nr2_shpo.okstate.edu/QueryResult.aspx?id=RS100002547

- Tulsa Race Riot Report (PDF), Oklahoma Historical Society: http://www.okhistory.org/research/forms/freport.pdf