In 1921, Tulsa, Oklahoma, was home to Greenwood, a thriving neighborhood so prosperous it earned the moniker “Black Wall Street.” This district stood as a powerful symbol of African American economic success and self-determination in a deeply segregated America. However, this beacon of Black achievement was brutally extinguished in a horrific act of racial violence that shook the nation. The Tulsa Race Massacre, ignited on May 31, 1921, decimated Black Wall Street, leaving an indelible scar on American history. The catalyst for this destruction was a racially charged report in the Tulsa Tribune, alleging an assault by a Black man on a white woman, sparking an eruption of white rage and violence that the investigative process could have potentially mitigated.

Accounts surrounding the encounter between Dick Rowland, a Black man, and Sarah Page, a white woman, in the Drexel Building elevator remain varied and unclear. Regardless of the truth, the Tulsa Tribune‘s inflammatory reporting acted as a fuse. Armed mobs, both Black and white, converged at the courthouse, escalating tensions to a breaking point. As skirmishes erupted and shots rang out, the outnumbered Black residents retreated to Greenwood. This withdrawal, however, did not quell the white mob’s fury. Instead, fueled by racial animosity, they pursued the Black residents, unleashing a wave of looting and arson that would obliterate homes and businesses in Greenwood.

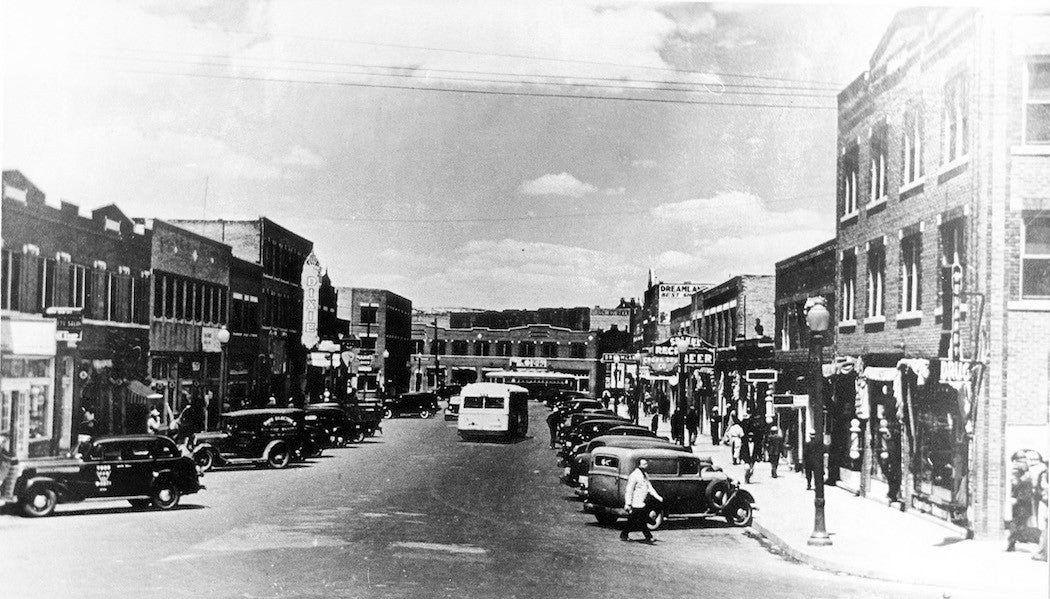

Archer at Greenwood, facing north (Greenwood Chamber of Commerce)

Archer at Greenwood, facing north (Greenwood Chamber of Commerce)

The scale of the devastation was immense. As Josie Pickens poignantly described in Ebony, the massacre left nine thousand people homeless and reduced a vibrant community to ashes. Black Wall Street was not just any neighborhood; it was, as Pickens writes, “modern, majestic, sophisticated, and unapologetically black.” This self-made haven boasted banks, luxurious hotels, bustling cafes, upscale clothiers, modern movie theaters, and beautifully appointed homes. Greenwood even offered amenities considered luxuries at the time, such as indoor plumbing and a superior school system that provided exceptional education to Black children. This prosperity, in stark contrast to the struggles of many of their white neighbors, bred resentment. This envy, coupled with a racist desire “to put progressive, high-achieving African-Americans in their place,” fueled a wave of domestic white terrorism that aimed to dispossess Black residents of their wealth and community.

The rise of Black Wall Street was no accident; it was the result of deliberate effort and vision. Christina Montford, writing in the Atlanta Black Star, highlights the pivotal role of O.W. Gurley, a wealthy African American who arrived in Tulsa in 1906. Gurley purchased over 40 acres of land and purposefully ensured it was sold only to other African Americans. This act of economic empowerment created opportunities for Black individuals migrating from the intense oppression of states like Mississippi. The economic ecosystem within Greenwood thrived due to segregation. As Montford notes, a dollar in Greenwood circulated “36 to 100 times” within the community, remaining within Black Wall Street for almost a year before leaving. This economic self-sufficiency generated remarkable wealth. In fact, during this era, incredibly, “six black families owned their own planes” in Oklahoma, a state with only two airports at the time. The average income in Greenwood surpassed what minimum wage is today, showcasing the district’s extraordinary economic power.

Despite this remarkable economic success, the residents of Greenwood could not shield themselves from the pervasive racial hatred of the era. Disturbing firsthand accounts from Greenwood survivors paint a horrifying picture of the massacre. Eyewitness testimonies, as reported by Democracy Now!, allege that the Greenwood area was deliberately bombed with kerosene and/or nitroglycerin, intensifying the inferno and accelerating the destruction. While official accounts attempted to downplay the severity, claiming private planes were merely on “reconnaissance missions,” survivors’ stories expose a far more sinister reality of targeted aerial attacks.

Hannibal Johnson, author of Black Wall Street: From Riot to Renaissance in Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District, underscores the enduring injustice faced by the survivors and their descendants. Despite the Tulsa Race Riot Commission’s recommendations for reparations for property loss and the establishment of a scholarship fund (which was implemented for a limited time), the grander vision of economic revitalization for Greenwood never materialized into tangible support. The promised reparations, intended to heal the wounds of the massacre, were ultimately denied, leaving a legacy of unaddressed trauma and economic injustice.

In his sociological analysis, “The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921: Toward an Integrative Theory of Collective Violence,” Chris M. Messer delves into the deep-seated causes of the massacre. The rapid demographic shift in Tulsa, fueled by migration and job opportunities, resulted in the city having the largest African American population in Oklahoma. This demographic boom, coupled with growing demands for equality from the Black community, created a volatile environment. As Messer argues, the rapid change left “little time for adaptation among whites.” The burgeoning Black population and their economic achievements were perceived as a threat to the existing racial hierarchy. White animosity towards Black economic progress was a key factor igniting the riot. Improvements in Black “wages and working conditions” were misconstrued by some whites as a communistic threat, reflecting anxieties about changing social and economic power dynamics. Fundamentally, many whites resented the fact that Black Americans were no longer passively accepting a position of second-class citizenship.

Segregation itself, ironically, played a complex role in the events. While it fostered a thriving Black business community by limiting where Black residents could spend their money, it also created a closed economic loop that fueled resentment from whites outside of Greenwood. Messer explains that segregation “encouraged initiative, but also placed parameters by restricting African-American opportunities.” While Black businesses benefited from reduced competition for Black patronage, segregation also limited overall Black economic mobility and opportunities beyond Greenwood.

The Tulsa police force’s actions and inactions during the massacre further exacerbated the tragedy. Their leadership was demonstrably ineffective, allowing white mobs to gather and escalate the violence at the courthouse for hours before seeking adequate assistance. Even more damning, the police actively participated in the riot by indiscriminately deputizing white individuals, arming them and effectively swelling the ranks of the violent mob. This blatant bias was further underscored by the police’s discriminatory actions: arresting Black residents en masse and interning them in detention camps while not arresting any white rioters during the massacre itself. This complete disregard for due process and equal protection under the law highlighted the systemic racism deeply embedded within Tulsa’s institutions.

Politicians and the media actively contributed to the distorted narrative of the Tulsa Race Massacre, falsely portraying it as a Black uprising. Tulsa newspapers, such as the Tulsa World, frequently employed dehumanizing language, referring to Greenwood as “Little Africa” and “n—–town.” Black residents were routinely stereotyped as criminals, labeled as “bad n—–s” engaging in illicit activities like drinking, drug use, and gun violence. This relentless negative portrayal in the media, coupled with the rhetoric of government officials, deeply influenced public perception. As Messer notes, white politicians and residents generally viewed the Black community “as predisposed to crime and in need of social control.” This pervasive assumption of Black criminality served as a justification for the deadly violence unleashed on Black Wall Street, framing it as a necessary act of subjugation.

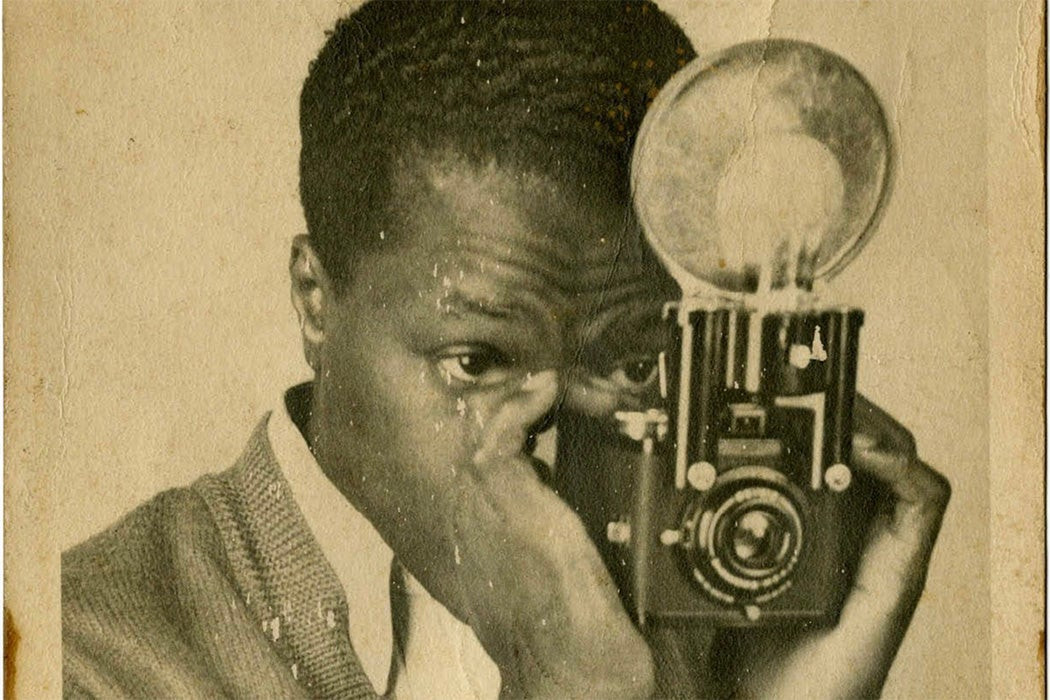

Photograph of Mr. Harrison Williams Holding a Camera

Photograph of Mr. Harrison Williams Holding a Camera

The Tulsa World newspaper further inflamed racial tensions by suggesting that the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), a known terrorist organization promoting white supremacy through violence, could “restore order in the community.” This suggestion from a mainstream newspaper legitimized and promoted white supremacy. It was a time of rising Black Nationalist organizations who refused to succumb to KKK intimidation and demanded equality. White society responded to this Black pride and these demands for equality with increased “social control, including segregation, lynchings, and pogroms,” as Messer describes. Further analysis by Messer and Patricia A. Bell in “Mass Media and Governmental Framing of Riots: The Case of Tulsa, 1921,” details how media framing ignited tensions, portraying Black aspirations for socioeconomic advancement and civil rights as a direct threat to white dominance. Framing Black people as inherently criminal served to perpetuate the narrative of Black inferiority, reinforce Jim Crow segregation, and rationalize the violent enforcement of racist ideology.

This racial framing directly legitimized the white mob’s actions “at the courthouse and the subsequent destruction of the Greenwood area.” Unsurprisingly, Black residents rightly perceived the events not as a riot, but “as a massacre of their community.” The destruction of Black Wall Street was fundamentally driven by a widespread white “generalized perception that African-Americans were ‘out of line’” and needed to be violently forced “back in their place.”

Despite enduring racial discrimination and the oppressive constraints of Jim Crow segregation, Greenwood stood as irrefutable proof of Black entrepreneurial capability and economic success. Messer’s analysis points to compelling “evidence that whites perceived African-Americans as an economic threat to the city.” For those invested in maintaining Black subjugation, witnessing Black prosperity and the dismantling of racist stereotypes was simply intolerable.

Walter F. White of the NAACP visited Tulsa shortly after the massacre. His report in The Nation highlighted the role of Black economic success in the district’s destruction. White noted Tulsa’s explosive growth during the oil boom, surging from 18,182 residents in 1910 to nearly 100,000 by 1920. He likened the city’s newfound wealth to the California Gold Rush. However, this prosperity, when extended to the Black community, triggered resentment among lower-class whites.

Many white residents clung to a belief in their “divinely ordered superior race.” This sense of superiority was challenged by the undeniable economic achievements within Greenwood. White’s report highlighted the significant Black wealth in Oklahoma at the time, including three Black millionaires and numerous individuals with substantial assets. Tulsa itself boasted particularly impressive figures, with multiple Black residents possessing fortunes ranging from $25,000 to $150,000.

White concluded that many white Oklahomans, originally from states like “Mississippi, Georgia, Tennessee, [and] Texas,” carried deep-seated “anti-Negro prejudices” from the Deep South. He offered a scathing assessment of Oklahoman whites, characterizing them as “lethargic and unprogressive by nature,” resentful of Black progress surpassing their own. He recounted a specific incident where a white employee, consumed by resentment, destroyed his Black boss’s printing plant, an act of violence that resulted in his own death amidst the mob he incited.

The destruction of Black Wall Street was not a random act of violence; it was a deliberate dismantling of a successful African American community. Messer argues that “the destruction of the community was rationalized as a necessary and natural response to put them back in their place.” The economic incentives were also undeniable. Within two days of the massacre, the mayor established a Reconstruction Committee, not to rebuild Greenwood for its residents, but to redesign it for industrial purposes. Black landowners were offered unfairly low prices for their devastated properties, preying on their vulnerability and desperation. White buyers offered meager sums, exploiting the survivors’ dire circumstances to seize valuable land.

Ultimately, the destruction of Black Wall Street reveals a disturbing truth about American capitalism and racial power dynamics. African Americans in Greenwood posed a “geographical problem because their community was situated in an ideal location for business expansion.” The government and private industry colluded to depress land values and reinforce white dominance in Tulsa. The resentment of poorer whites was manipulated by elite whites, who used them as instruments to acquire more land, wealth, and power. The state, through law enforcement’s inaction and complicity, effectively endorsed and supported the Tulsa Race Massacre for its own capitalistic gains.

Throughout American history, capitalism has often functioned to concentrate power and wealth in the hands of a white elite. When Black communities achieve economic strength, like Black Wall Street, they challenge this established power structure. The socioeconomic progress of African Americans in Greenwood was perceived as a threat to white-dominated American capitalism. The brutal destruction of Black businesses and homes served to reassert white supremacy and maintain the racial hierarchy.

While Greenwood was rebuilt by the 1940s, the integration era of the Civil Rights movement prevented it from regaining its former prominence. The tragic fate of Black Wall Street serves as a stark reminder that systemic racism remains deeply embedded within American society. As long as power remains concentrated within a predominantly white elite, the economic system can be manipulated to uphold and advance white supremacy, perpetuating racial inequality despite individual Black achievement.