Bayard Street, a vibrant artery in the heart of Manhattan’s Chinatown, is a captivating microcosm of New York City’s rich immigrant history and ever-evolving cultural landscape. Spanning just four blocks between Baxter Street and Bowery, this bustling street encapsulates the essence of Chinatown, offering a sensory feast of sights, sounds, and smells that are distinctly its own. From the tantalizing aromas of exotic spices and freshly baked goods wafting from bustling markets and eateries to the lively chatter of residents and the playful shouts of children, Bayard Street is a place where tradition and modernity intertwine.

While not always the family-friendly haven it is today, Bayard Street’s story is one of constant transformation. Once a neighborhood populated by Eastern European immigrants, it has morphed into the vibrant Chinatown we know and love. Today, it stands as a testament to the enduring spirit of immigrant communities in New York City, a place where generations of families have built their lives and contributed to the city’s dynamic tapestry.

A Stroll Through Time: The Historical Layers of Bayard Street

Bayard Street’s history stretches back centuries, its name a nod to Nicholas Bayard, the nephew of Peter Stuyvesant, a prominent figure in New York’s early Dutch history. Bayard, an influential political figure in his time, owned property in what is now modern Chinatown. Despite facing political turmoil and temporary forfeiture of his land, the Bayard family held onto their property until 1760, when they began selling parcels that would eventually form the city blocks of Chinatown.

A historical image capturing the essence of Bayard Street in Manhattan, showcasing its evolving urban landscape.

In the 19th century, Bayard Street took on a different character, becoming a focal point for a wave of Eastern European immigrants. However, this period was also marked by incidents of violence, as reflected in New York Times articles from the late 1800s reporting on shootings and crime on Bayard Street. These historical accounts paint a stark contrast to the present-day family-oriented atmosphere, highlighting the dramatic shifts in the street’s social fabric over time.

Today, Chinatown is experiencing another wave of change. The influx of Mandarin speakers from mainland China is gradually reshaping the linguistic landscape of the neighborhood, once dominated by Cantonese speakers from Southern China and Hong Kong. This demographic shift adds another layer of complexity to Bayard Street’s identity, reflecting the continuous evolution of New York City’s immigrant communities.

Tai Pun Residents Association: A Glimpse into Community Roots

Nestled on Bayard Street is the Tai Pun Residents Association at 51 Bayard St, a seemingly unassuming building that holds significant cultural weight. This organization, often overlooked in mainstream narratives, provides a fascinating glimpse into the intricate social networks within Chinatown.

The Tai Pun Residents Association building on Bayard Street, Manhattan, a hub for the Dapengese community and their cultural preservation efforts.

Founded in 1919, the Tai Pun Residents Association is the oldest Da Peng organization in New York City. Da Peng refers to an area in Southern China near Hong Kong, and the association serves as a vital center for Dapengese immigrants. It’s a place where they can maintain their cultural heritage, speak their unique Dapeng dialect, and foster a sense of community far from their ancestral homes. The Association’s values, emphasizing respect for elders and Chinese nationalism, are reflected in their annual celebrations of the People’s Republic of China national day. Despite its low online profile, the Tai Pun Residents Association stands as a testament to the enduring importance of community organizations in preserving cultural identities within immigrant enclaves like Chinatown.

Experiencing Bayard Street: A Walk Through the Senses

A walk down Bayard Street is an immersive experience that engages all the senses. Starting from Baxter Street, the western end of Bayard Street, one is immediately greeted by the vibrant energy of Chinatown. Even a simple attempt to photograph the bilingual street sign can be interrupted by the unexpected, as illustrated by the author’s encounter with a police motorcade entering the Manhattan Detention Center nearby.

A street-level view of Bayard Street, Manhattan, capturing the daily life and architectural details that define its unique character.

Moving eastward towards Mulberry Street, Columbus Park unfolds to the south, a green oasis where elderly Chinese residents practice Tai Chi and socialize. The corner of Mulberry and Bayard reveals historical landmarks like the old schoolhouse, now home to the Chinatown Manpower Project and the Chen Dance Center, institutions deeply rooted in the community. The subtle details of the streetscape, from pagoda-style lamps to Chinese characters adorning storefronts, further emphasize the unique cultural identity of Bayard Street.

However, this seemingly peaceful street has a historical undercurrent of crime. The author recounts the curious kidnapping tale of 1899, where a letter found on Bayard Street initiated a police investigation into a fabricated abduction. This anecdote, along with numerous reports of shootings in the late 19th century, serves as a reminder of the street’s complex and sometimes turbulent past.

Bayard Street in Maps and Imagination

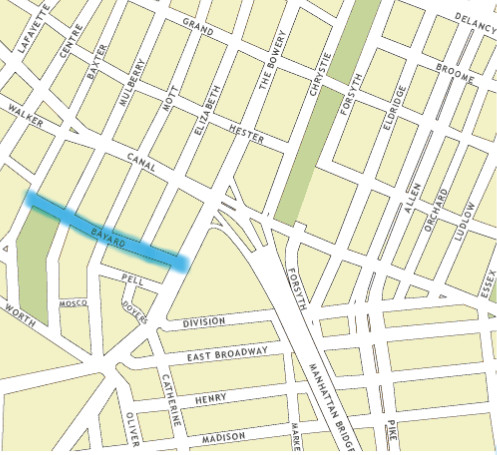

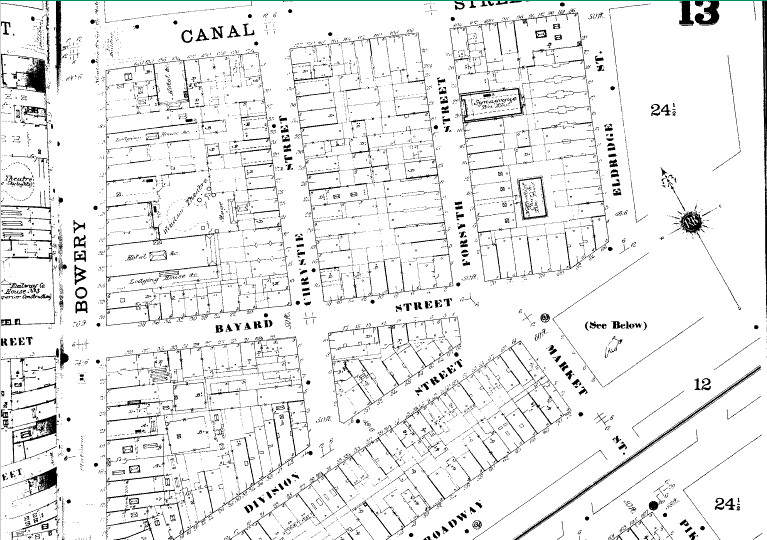

Delving into historical maps reveals further transformations of Bayard Street. Sanborn maps from the late 19th century show Bayard Street extending further east, nearly double its current length, stretching into what is now the Lower East Side. This historical cartography illustrates how urban development, particularly the construction of large apartment complexes and infrastructure projects like the Manhattan Bridge, has reshaped the street’s physical boundaries over time.

A historical map illustration showing the extended Bayard Street in Manhattan, before urban development altered its original length and boundaries.

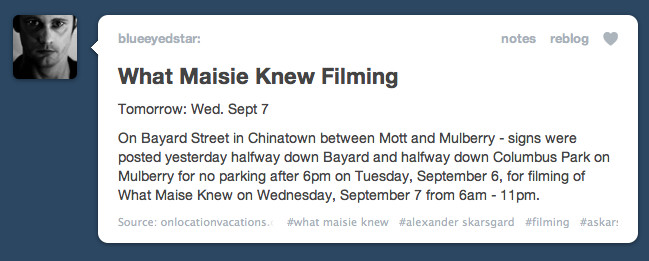

Beyond historical documents, Bayard Street has also subtly permeated the realm of fiction and film. Literary mentions in Arthur Bartlett Maurice’s “New York in Fiction” and Kevin Baker’s “Dreamland” offer glimpses of Bayard Street in the early 20th century, often associated with the gritty realities of tenement life and the Five Points neighborhood. More recently, Bayard Street served as a filming location for the movie “What Maisie Knew,” bringing a touch of Hollywood to this unassuming Chinatown street.

Bayard Street After Dark: A Different Kind of Energy

As day turns to night, Bayard Street takes on a different ambiance. While Chinatown generally quiets down after 8:30 PM, Bayard Street retains a subtle energy, particularly around its eateries. Restaurants like Xi’an Famous Foods stay open later, attracting a mix of locals and those in the know. Even on Halloween night, the street is surprisingly active, though the crowds are more likely to be teenagers than trick-or-treaters.

A nighttime view of Bayard Street in Manhattan, showcasing the vibrant storefronts and illuminated signs that come alive after dusk.

Columbus Park, while serene during the day, transforms into a social hub in the evening. Elderly residents gather to play cards and enjoy traditional Chinese music, creating a lively, community-centric atmosphere that contrasts with the quieter streets. While some may perceive Chinatown at night as less safe, Bayard Street maintains a sense of community presence, particularly within Columbus Park.

Bayard Street: A Culinary and Pop Culture Destination

Bayard Street has gained recognition in popular culture, particularly for its culinary offerings. Food shows like Anthony Bourdain’s “No Reservations” and Andrew Zimmern’s “Bizarre Foods” have featured Xi’an Famous Foods, highlighting its authentic and unique cuisine from Northern China. Chinatown Ice Cream Factory, another Bayard Street institution, is renowned for its Asian-inspired flavors and has become a must-visit destination for both locals and tourists, even attracting celebrity sightings.

Actor Alexander Skarsgard spotted filming on Bayard Street in Manhattan, highlighting its occasional role as a film set.

These culinary hotspots contribute to Bayard Street’s identity, drawing visitors into the heart of Chinatown and showcasing the diverse flavors and traditions of Chinese culture. They represent a blend of local authenticity and tourist appeal, making Bayard Street a compelling destination for food enthusiasts and cultural explorers.

Sounds of Bayard Street: An Urban Symphony

Drawing parallels to the concept of “street sounds” in interwar Harlem, Bayard Street possesses its own distinct soundscape. While Harlem was defined by the rhythms of jazz, Bayard Street’s sonic identity is woven from the tapestry of Chinese dialects, bustling market noises, and traditional music. During Chinese New Year, this soundscape explodes into a vibrant symphony of firecrackers, drums, and cymbals accompanying the Lion Dance, transforming the street into a stage for cultural celebration.

A glimpse into the vibrant community life on Bayard Street, Manhattan, showcasing the park as a gathering place for social activities and cultural exchange.

This sonic environment, while perhaps perceived as “noise” to outsiders, represents the vitality and cultural vibrancy of Bayard Street’s community. It’s a sound of claiming public space, of cultural expression, and of a community thriving in the heart of a global city.

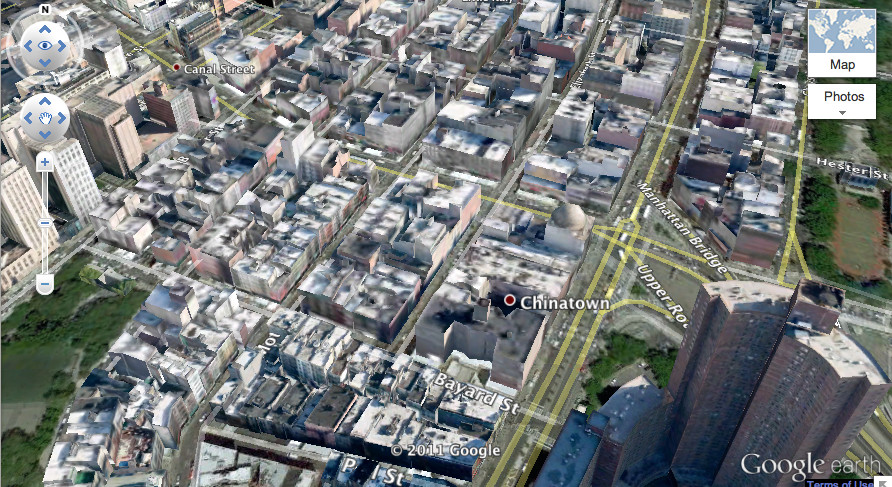

Bayard Street in the Digital Age: Mapping the Urban Tapestry

In the digital age, Bayard Street gains another layer of representation through online platforms like Google Earth. While digital views may highlight the street’s lower building heights compared to surrounding areas, they also reveal the richness of user-generated content. Platforms for restaurant reviews and online city guides contribute to a digital “urban tapestry” of Bayard Street, layering personal experiences and local knowledge onto the virtual map.

A digital representation of Bayard Street in Manhattan, showing its urban context and surrounding cityscape through a map interface.

This digital layer enhances the real-world experience of Bayard Street. Prospective visitors can access a wealth of information, from restaurant reviews to walking tours, enriching their understanding and appreciation of the street before even setting foot there. This interplay between the physical and digital realms further shapes the identity of Bayard Street in the 21st century.

Conclusion: Bayard Street – A Community Rooted in Heritage and Change

Bayard Street in Manhattan stands as a compelling case study in urban cultural dynamics. It embodies Sharon Zukin’s concept of immigrant communities exerting influence on public institutions and shaping the urban landscape. With a significant Asian population, predominantly Chinese, Bayard Street showcases its heritage through bilingual signs, pagoda-style lampposts, and a strong sense of community.

Daytime activity in Columbus Park on Bayard Street, Manhattan, a vibrant hub for elderly Chinese residents and their daily social and recreational activities.

Columbus Park, bordering Bayard Street, serves as a microcosm of this community, a public space actively utilized and shaped by its elderly Chinese residents. Bayard Street itself, while seemingly unassuming, possesses a unique atmosphere, a blend of everyday life and cultural distinctiveness. It’s a place where the past and present converge, where immigrant heritage thrives amidst urban change, and where a sense of community endures in the heart of Manhattan. Bayard Street is more than just a location; it’s an experience, a feeling, and a vital thread in the rich urban tapestry of New York City.

Works Cited

1: “The Bayard-Street Shooting-Harrington Convicted and Sentenced to Ten Years’ Imprisonment.” New York Times (1857-1922): 2. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times (1851-2007) with Index (1851-1993). Jan 10 1873. Web. 13 Sep. 2011 https://ezproxy.library.nyu.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/93307966?accountid=12768>.

2: Semple, Kirk. “Mandarin Eclipses Cantonese, Changing the Sound of Chinatown – NYTimes.com.” The New York Times – Breaking News, World News & Multimedia. 21 Oct. 2009. Web. 13 Sept. 2011. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/22/nyregion/22chinese.html?pagewanted=1>.

3: Landmarks Preservation Commission. “192 Grand Street House.” NYC.gov. 16 Nov. 2010. Web. 13 Sept. 2011. http://home2.nyc.gov/html/lpc/downloads/pdf/reports/2412.pdf>.

4: “Tai Pun Residents Association.” Wikipedia. Web. 20 Sept. 2011. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tai_Pun_Residents_Association>.

5: Morris, Brian. “What We Talk about When We Talk about ‘walking in the City’1.”Cultural Studies 18.5 (2004): 675-97. Print.

6: “Strange Kidnapping Tale.” New York Times (1857-1922): 14. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times (1851-2007). Jun 20 1899. Web. 4 Oct. 2011 https://ezproxy.library.nyu.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/95678453?accountid=12768>.

7: Sanborn-Perris Map Co., Ltd. “Jusmance Maps of the City of New York.” Map.Digital Sanborn Maps, 1867-1970. Web. 15 Oct. 2011. http://http://sanborn.umi.com/ny/6116/dateid-000001.htm?CCSI=2872n>.

8: Baker, Kevin. Dreamland. New York: HarperCollins, 1999. Print

9: Maurice, Arthur Bartlett. New York in Fiction. New York: Dodd, Mead and, 1901. Print.

10: “September 7, 2011 Movie and TV Filming Locations including The Playboy Club, Man of Steel, Imogene, R.I.P.D. & More.” On Location Vacations. 7 Sept. 2011. Web. 24 Oct. 2011. http://www.onlocationvacations.com/2011/09/06/wednesday-september-7-filming-locations-in-nyc-l-a-atlanta-more-including-what-to-expect-dark-knight-rises-person-of-interest/>.

11: http://ny.eater.com/tags/xian-famous-foods

12: Corbould, Clare. “Streets, Sounds and Identity in Interwar Harlem.” Journal of Social History 40.4 (2007): 859-94. Print.

13: Galloway, Anne. “Intimations of Everyday Life: Ubiquitous Computing and the City.”Cultural Studies 18.2-3 (2004): 384-408. Print.

14: Zukin, Sharon. “Whose Culture? Whose City?” The Cultures of Cities. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1995. 1-47. Print.