Some albums are born to ignominy; others have ignominy thrust upon them. 1978’s Shakedown Street undeniably falls into the latter category, a perplexing entry in the Grateful Dead’s extensive discography that continues to divide fans and critics alike. This album, often described as lukewarm and vapid, represents a significant departure from the band’s improvisational roots, a detour that left many questioning the Dead’s creative direction. With tracks like “France” and “If I Had the World to Give,” Shakedown Street seemed to suggest a band struggling to find its identity amidst the changing musical landscape of the late 1970s.

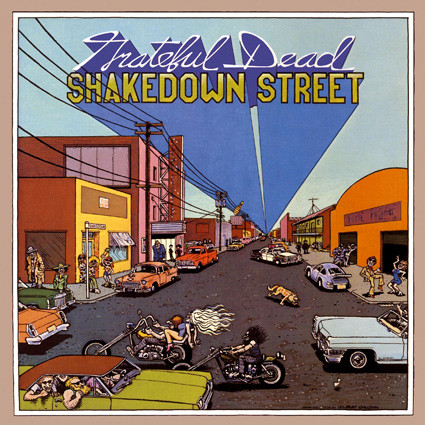

Grateful Dead Shakedown Street album cover featuring cartoon characters in a city street scene, reflecting the album's urban and disco influences.

Grateful Dead Shakedown Street album cover featuring cartoon characters in a city street scene, reflecting the album's urban and disco influences.

The critical reception was far from kind. Robert Christgau, a prominent music critic, famously lamented, “I remember Robert Hunter when he was making up American myths,” highlighting a perceived decline in the lyrical depth that had become synonymous with the Grateful Dead. Bob Weir’s yearning vocals on “I Need a Miracle” inadvertently echoed the band’s predicament, though the miracle required was not divine intervention, but a creative resurgence.

The Long Strange Trip to Shakedown Street: A Decline in Progress?

Shakedown Street wasn’t an isolated misstep; it arguably marked a continuation of a gradual artistic drift that began earlier in the decade. While 1973’s Wake of the Flood signaled a subtle shift, the slide accelerated with 1977’s Terrapin Station. Terrapin Station, despite moments of brilliance, introduced a slicker, more produced sound, exemplified by its prog-rock influenced title track and the somewhat jarring “Dancin’ in the Streets.” This cover, far from being a celebratory anthem, felt like a symptom of a band grappling with creative exhaustion.

For devoted Deadheads, the release of Shakedown Street was a moment of bewildered disappointment. Purchasing and listening to the album felt akin to experiencing a sonic hallucination. Were Donna Jean Godchaux’s contributions truly representative of the Grateful Dead? Was their rendition of “Good Lovin’,” a classic rock and roll staple, a sign of creative bankruptcy? The fact that this album was produced by the esteemed Lowell George, known for his work with Little Feat, only deepened the sense of confusion.

Disco Dead? Unpacking the “Abomination”

The realization that the Grateful Dead’s tenth studio album was largely underwhelming, save for some intriguing percussion work, was a harsh awakening. The return of Mickey Hart to the drumming fold, alongside Jordan Amarantha’s contributions, offered some sonic textures, but couldn’t salvage the core issues. For some listeners, the ultimate shock came with the title track, “Shakedown Street,” which felt undeniably… disco-infused. “Disco Dead” – the very notion seemed apocalyptic, a sign that the band had succumbed to the prevailing trends rather than forging their own path.

Dissecting Shakedown Street is not a pleasant task. It’s akin to a musical autopsy, revealing the flaws beneath the surface. The cover of “Good Lovin’,” while featuring some interesting percussion, ultimately falls flat, with Bob Weir’s vocals sounding uncharacteristically smug. Similarly, “I Need a Miracle,” despite Matthew Kelly’s harmonica and Keith Godchaux’s piano work, is weighed down by a generic guitar riff and Weir’s somewhat forced vocal delivery.

Glimmers of Hope and Deeper Disappointments

“All New Minglewood Blues” stands out as a relative highlight, showcasing Garcia’s guitar work and solid drumming, even if Weir’s vocals remain a point of contention for some. “Fire on the Mountain,” while not universally loved due to its syncopation and Garcia’s reggae-tinged vocals, is another track that offers a degree of redemption. However, these brighter spots are overshadowed by tracks like “France,” with its jarring mix of steel drums and what many perceive as cliché-ridden lyrics. The combined vocals of Donna Godchaux and Bob Weir on “France” are often cited as particularly weak, and even Garcia’s guitar solo is described, unfavorably, as saxophone-like.

“From the Heart of Me,” a Donna Jean Godchaux feature, is frequently cited as one of the Grateful Dead’s weakest songs. While containing some pleasant guitar work from Garcia, it lacks any discernible Grateful Dead identity, sounding generic and out of place within their catalog. Instrumentals like Hart and Kreutzmann’s “Serengetti,” intended as a snippet of their “Drums & Space” explorations, come across as filler. “If I Had the World to Give,” a Garcia-led ballad, despite heartfelt vocals, is criticized for being drawn-out and lackluster, failing to live up to Garcia’s usual standards.

Stagger Lee and Shakedown Street: Moments of Intrigue Amidst the Muddle

Garcia fares better on “Stagger Lee,” delivering stronger vocals and guitar work. This traditional song, adapted by the Dead, offers a glimpse of the band’s potential. Finally, the title track, “Shakedown Street,” is perhaps the most controversial. Its disco-inspired rhythm and production choices are jarring to many Grateful Dead purists. While Garcia’s guitar playing remains technically proficient, its jazzy, syncopated style, combined with slick backing vocals and Gibb Brothers-esque drumming, feels out of sync with the band’s core sound.

The Verdict: A Creative Dead End?

Ultimately, the most praiseworthy aspects of Shakedown Street are its Gilbert Shelton-designed album cover and the fact that it marked the end of the Godchauxs’ tenure with the band. Critics at the time echoed Christgau’s sentiment. Rolling Stone deemed it an “artistic dead end,” with “disco tinges” exacerbating the album’s shortcomings. “Catastrophe” and “boondoggle” are apt descriptors for an album that lacks both memorable songs and compelling performances.

Unless you are a die-hard Deadhead or blinded by nostalgia, Shakedown Street is widely considered a turning point, marking the decline of the Grateful Dead as a consistently innovative songwriting force. While some might argue for later albums like In The Dark and Built To Last, these are generally seen as pale imitations of the band’s earlier brilliance, particularly the golden era of American Beauty and Workingman’s Dead. As Christgau wisely observed, “One problem with the cosmic is it doesn’t last forever.” In the Grateful Dead’s case, their cosmic peak, for many, faded well before Shakedown Street.

GRADE: D